At 93, this Rosie is still riveting

Elinor Otto picked up a riveting gun in World War II, joining the wave of women taking what had been men’s jobs. These days she’s building the C-17.

E

linor Otto braces her slight frame and grips the riveting gun with both hands, her bright red hair and flowered sweater a blossom of color in Long Beach's clanking Boeing C-17 plant.

Boom, boom, boom.

She leans back as the gun's hammer quickly smacks the fasteners into place.

Then she puts the tool in a holster and zips around a wing spar to grab a handful of colorful screw-on backs, picking up another gun along the way to finish them off. Her movements are deft and precise.

"Don't get in her way, she'll run you over," a co-worker says with a smile.

Otto finishes a section of fasteners, looks up and shrugs.

"That's it."

Just another day at the office for a 93-year-old "Rosie the Riveter" who stepped into a San Diego County factory in 1942 — and is still working on the assembly line today.

Otto is something of a legend among her co-workers on the state's last large military aircraft production line. And her legend is growing: She was recently honored when Long Beach opened Rosie the Riveter Park next to the site of the former Douglas Aircraft Co. plant, where women worked during World War II.

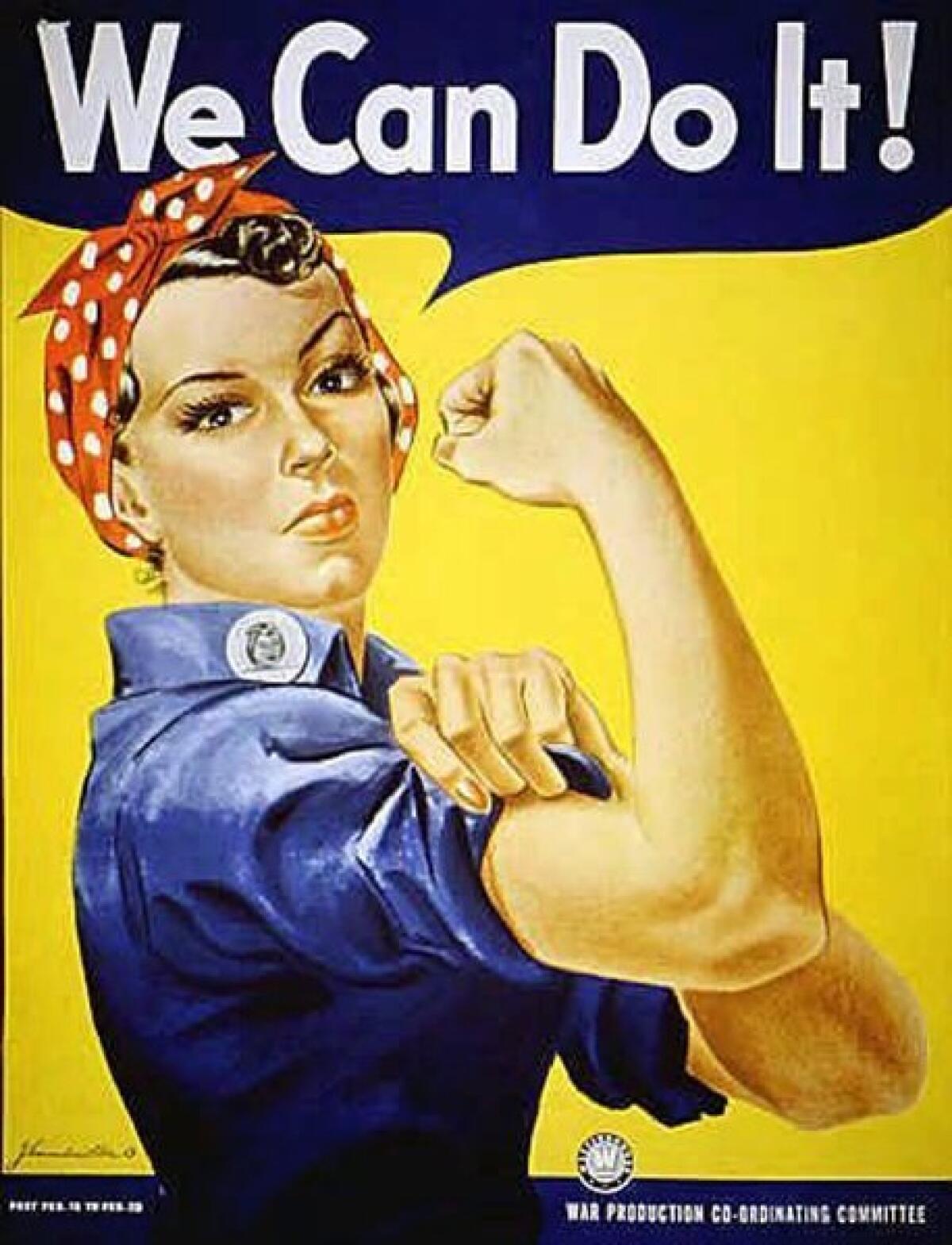

"She says, 'We can do it!' and I'm doing it!" Otto says, flexing her thin arm and laughing, mimicking the iconic poster.

Elinor Otto, 93, prepares to rivet a wing while working at Boeing in Long Beach. "Don't get in her way, she'll run you over," a co-worker says. (Genaro Molina, Los Angeles Times) More photos

If she were younger, she jokes, she would look at herself now and wonder, "What's that old bag still doing here?"

But Otto seems to have more energy than those half a century younger.

"I wish I was in as gooda shape as she's in at my age," says fellow structural mechanic Kim Kearns — who is 56.

Otto is out of bed at 4 a.m. and drives to work early to grab a coffee and a newspaper before the 6 a.m. meeting. In the Boeing lot, she parks as far from the plant as possible so she can get some exercise. Every Thursday, she brings in cookies and goes to the beauty parlor to have her hair and nails touched up after her shift ends.

"She's an inspiration," says Craig Ryba, another structural mechanic. "She just enjoys working and enjoys life."

Otto was beautiful, with bright blue eyes and dark hair piled high, when she joined a small group of women at Rohr Aircraft Corp. in Chula Vista during World War II. The bosses threatened to give demerits to the men who stood around trying to talk to her — so Otto's suitors left notes for her in the phone booth, where she called her mother every day.

Back then, everyone worked for the war effort, Otto says, so they didn't think much of their jobs — it was tough to find good ones. World War II was all-consuming, with product rationing and scrap metal collections, and men leaving for the war.

When I go to heaven, I hope God keeps me busy!"—Elinor Otto

Otto joined the war effort with her two sisters, one who worked alongside her at Rohr, the other a welder in a Bay Area shipyard. She was newly single with a young son.

"During those days, we could hardly find an apartment that would let you rent with kids. My goodness, they're going to go to war someday and they can't even live in an apartment," says Otto, who had to board her son out during the week. "It cost $20 a week, and it was hard because I made 65 cents an hour."

At the plant, she would make the others laugh at how fast she could rivet, she says, quickly moving her hands and stomping her feet to demonstrate.

The men resented the women at first — smoking was banned and shirts had to stay on — and doubted that they could get the job done, she says.

"It turned out we worked better than them, faster, because they were so sure of themselves."

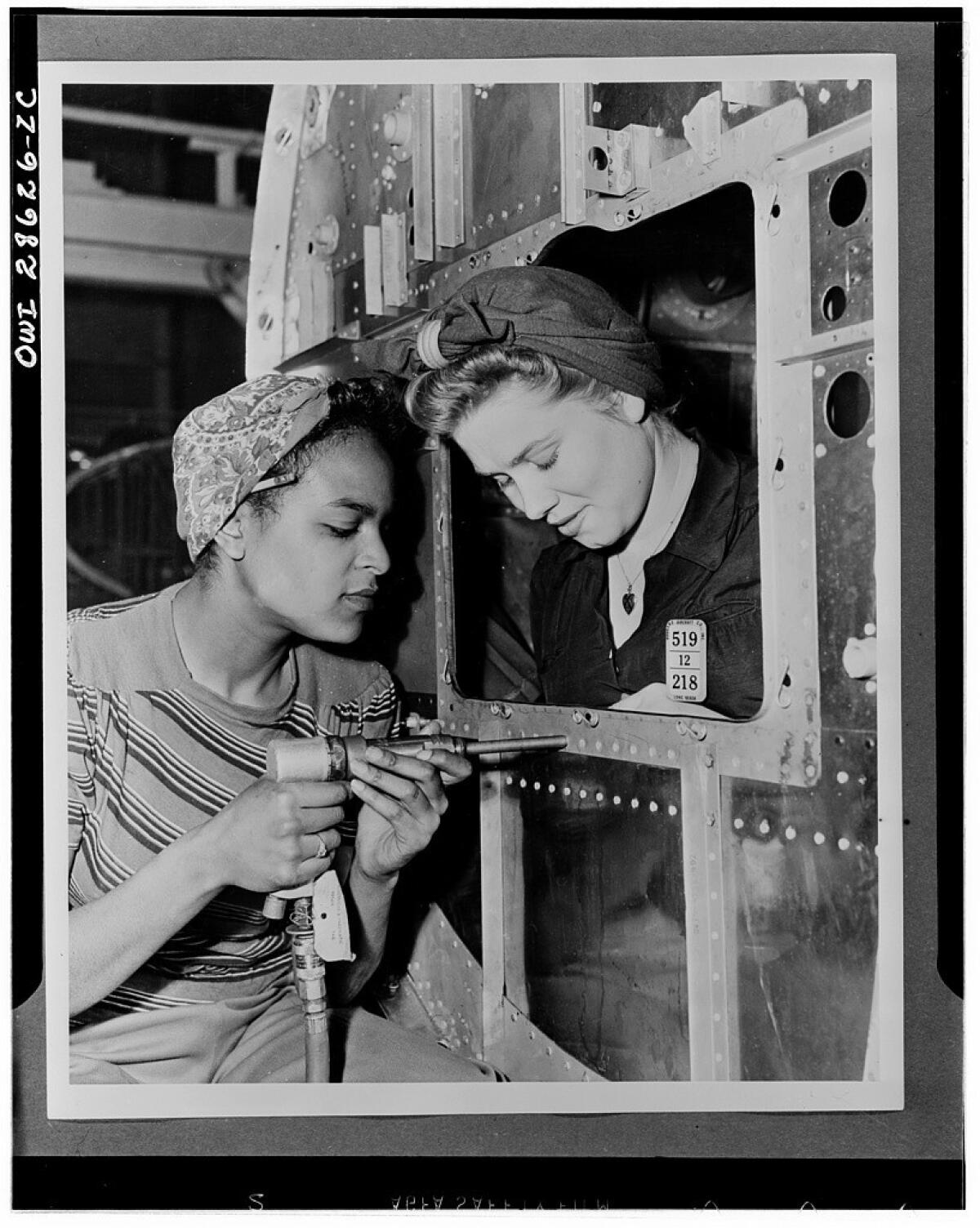

Dora Miles and Dorothy Johnson at the Long Beach plant of Douglas Aircraft Co. Douglas' factories were considered an industrial melting pot as men and women of 58 national origins worked side by side during the war. (Library of Congress) More photos

And on the days they didn't feel like going in, she and the girls would put "Rosie the Riveter" by the Four Vagabonds on their 78 phonograph. They would sing and bop along to the music to get themselves motivated and out the door.

All the day long,

Whether rain or shine,

She's a part of the assembly line.

She's making history,

Working for victory,

Rosie — BRRRR — the Rivet-er.

Days after the war ended, Otto and other women were let go as men returned home.

"They needed us at one time, and when the war was over, they let us go," she says. "That's how it was."

Thousands of women flocked to California to work at aircraft factories during the war. The first wave was mostly single women, but wives, mothers, groups of friends and sisters followed.

It was tough work, with the challenge of finding child care and the pressures of a society shaken by war and changing norms, says Long Beach Councilwoman Gerrie Schipske, who wrote the book "Rosie the Riveter in Long Beach."

After a hard day's work, men and even other women would sometimes harass Rosies if they went home in their dirty pants or overalls instead of changing into a skirt and sweater, she says.

Elinor Otto, center, walks with co-workers Craig Ryba, left, and Kim Kearns at Boeing in Long Beach. (Genaro Molina, Los Angeles Times) More photos

"It's an interesting struggle that women went through just simply because they were trying to do something to help end the war," Schipske says. "It was an incredible amount of work they had to do."

Interest in Rosies peaked in the 1970s and '80s, as the "We Can Do It" poster was rediscovered and became a symbol of the women's movement, Schipske says. Now, families are becoming more aware of relatives' contributions during the war, she says.

A year ago, Otto would have said that working during the war was no big deal, grandson John Perry, 43, says. But as more people talk to her about her history, he says, the more she realizes she really did something important.

"You've saved American lives and you've been saving American lives your whole life," Perry says he tells his grandmother. "It's a powerful story, a positive story, and one hell of a tribute to the female work force."

Growing up, Perry says, his grandmother taught him etiquette and culture when he was shuttling back and forth between parents. When he wrote letters to her, she corrected his spelling in neat red pen and sent them back.

"As long as her eyes are open," Perry says, "she's going."

As long as her eyes are open, she's going."— John Perry, riveter Elinor Otto's grandson

After the war ended, Otto tried other jobs, but sitting in an office drove her nuts — she hates being still.

Car-hopping worked out until roller skates were added to the uniform. ("I'da broke my neck, skating and holding food! No, no, no.")

So she worked for Ryan Aeronautical Co. in San Diego for 14 years, until she was laid off.

At a party nearly a year later, a girlfriend told her to get to Los Angeles as fast as she could. Douglas Aircraft was hiring women for the first time since the war. A car full of women left for Long Beach that night, she says, and were hired right away.

In its heyday, Otto says, the C-17 plant was fully staffed with a parking lot so big that workers put flags on their cars to find them in the sea of vehicles. Long Beach was a hub of production during the war and after, but in the decades since, the aerospace industry in the city has shrunk as demand for military aircraft has fallen. In mergers over those years, Douglas became McDonnell Douglas Corp., which later joined with the Boeing Co.

J. Howard Miller's poster, created for Westinghouse, has become one of the most iconic images of World War II (Associated Press Photos) More photos

But as the production at the C-17 plant dwindled and operations became more mechanized, "It was kinda like trimming back the bushes, you can see your neighbor again," Kearns says of meeting Otto a decade ago — after having worked at the same plant for more than 20 years.

"She tells us not to treat her any different," Ryba says. "She works that job just like any of us and sometimes maybe better."

Over the years, her crew has been supportive of Otto, who remarried and eventually divorced. Last year, when her son died, they surprised her by attending the graveside service. So many people showed up for her that she thought there was another funeral coming, she says with a tear in her eye and a squeeze of Kearns' hand.

On Sept. 12, the Air Force ended its 32-year relationship with the Long Beach plant as it received its 223rd and final cargo jet. Foreign sales are few and small, but will keep the plant running until late 2014. Boeing will soon make a decision about the future of the production.

The great-grandmother says she would like to retire soon as well, but she refuses to become a couch potato ("Gotta keep moving!"). She's worked so long for economic reasons — she cared for her mother and son for years — but also because of her endless energy.

"When I go to heaven," she says with a laugh, "I hope God keeps me busy!"

Follow Samantha Schaefer (@Sam_Schaefer) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Past is always a present for San Juan Capistrano preservationist

It would be like painting Mickey Mouse on the Vatican grounds. It would be like that."

Changing faiths at the Crystal Cathedral

Catholic on the inside, but kind of Protestant on the outside."

New Mexico's drought threatens a way of life

The sun is rising. I will keep working to maintain what I love so dearly."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.