Actors draw med school students into caregiver role

‘Standardized patients’ give aspiring doctors a chance to practice bedside manner before it’s for real. It’s a great gig.

David Solomon lay in bed, a sheet draped over his legs. His darkened bedroom was silent, except for the ticking of a clock on the wall. A box of tissues sat on a bedside table; a Hebrew-and-English siddur, or prayer book, rested on his lap.

The cancer that the 70-year-old cosmetics merchant had held at bay for 12 years was no longer responding to chemo. His breathing was labored, and his morphine-addled gaze wandered. It took all his effort to focus on the white-jacketed medical student who stood next to him.

"Even though we're done treating your lymphoma, we're still here to help," the student said, gently.

"I want to talk about hospice," Solomon croaked.

He had signed paperwork urging doctors to withhold interventions such as a feeding tube during his final weeks and thought he wanted to die here, at home. At the same time, he worried how his decision would affect his family.

"Do I want my family to walk into this room and the last memories be saying goodbye to me?" he asked.

The room fell quiet again. The medical student was still. Two of his classmates, in chairs nearby, dabbed their eyes. One reached past Solomon, grabbed a tissue and blew her nose.

"Time out!" their instructor shouted.

The patient sat up in his bed, pulled a canary-yellow yarmulke off his head and smiled.

"I am not David Solomon," actor Bob Rumnock told the students, "though we all will be at some point."

Rumnock is a member of a small but dedicated troupe of actors who portray patients at Los Angeles-area medical schools.

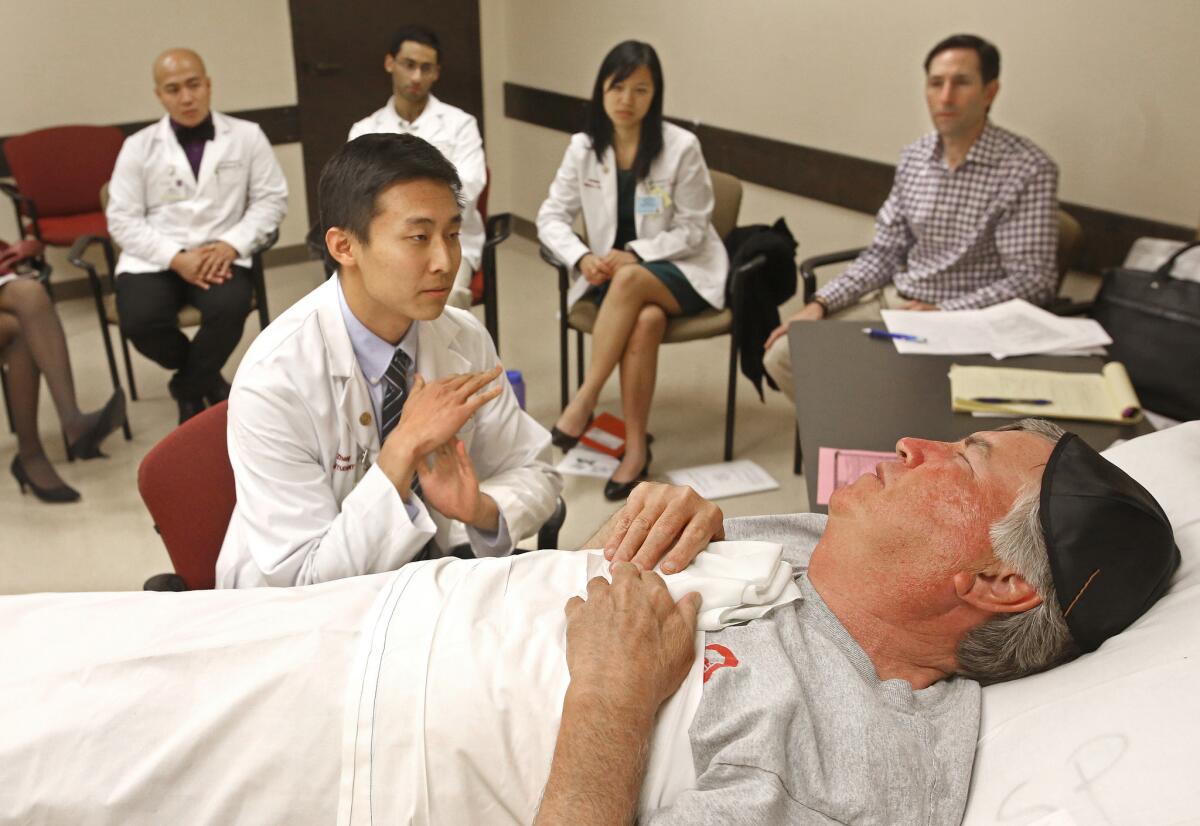

Stepping into carefully crafted but mostly unscripted roles, these so-called standardized patients help young medical students practice their bedside manner, testing out how it feels to place a hand on a dying patient's arm or ask a fidgety teen about her sexual history.

Ali Shannon Philander, right, receives guidance from clinical instructor Andrea Kachuck, left, while treating a hospice patient portrayed by actor Bob Rumnock. More photos

Medical educators and students love the exercise because it lets them practice interacting with patients, the core of a physician's work, without worrying about doing harm. For actors like Rumnock, 60, who hustles to make a living on stage, in movies ("Divergent," "The Lone Ranger") and on TV ("Scrubs," "Mad Men," "Weeds" and "Grey's Anatomy," among other shows) being an "SP" offers insight into their own medical care.

It's also a pretty good gig.

"It's some of the meatiest characters you can play, and it pays," said Rumnock, who gets $15 an hour for training and $20 an hour for the performances. "I love doing theater, but it doesn't pay the bills."

Actors have been doing this work at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, where Rumnock was playing David Solomon, for 50 years.

In 1964, Dr. Howard S. Barrows and Dr. Stephen Abrahamson, both professors at the medical school, published a paper in the Journal of Medical Education that described the use in neurology training of a "programmed patient" — an actress who had been trained to portray someone suffering from multiple sclerosis and interact with students performing a medical exam.

Medical schools at the time resisted using "simulated patients," calling it "too 'Hollywood,'" UC San Diego professor Peggy Wallace wrote decades later in the journal Caduceus.

By the 1980s, however, medical schools came around, arriving at a uniform approach in which every student would interact with an actor who behaved in a prescribed manner — and who was also carefully trained to provide useful feedback.

Today, many programs use standardized patients. At USC, first-year students see SPs nine times; second-year students, not quite as often. Doctors-to-be in the U.S. encounter SPs when they take their licensing exams.

Rumnock reported for work about 1 p.m., slipping into a green room at USC's medical school campus in Boyle Heights.

The scene resembled a casting call, with 16 actors — all white men in various stages of middle age, all dressed in pajamas or sweats — buzzing around nervously, chowing on pizza and sodas.

Denise Souder, second from right, assistant professor at the Keck School of Medicine in Boyle Heights, greets actors gathered to play the role of David Solomon. More photos

It was a scene familiar to Solomon, who in 14 years as an SP has played alcoholics; homeless patients; "a meningitis case where the pain level is a 9/10"; a diabetic land developer who "has an answer for everything"; and — what might be his favorite character — the thrice-widowed Gary Wilson, who whiles away his nights drinking vodka and watching TV with a couple of neighbors.

"He's the saddest, saddest man," Rumnock said of Wilson, with a dramatic sigh.

Rumnock had played Solomon five times before, and he had refamiliarized himself with the details of the case using an eight-page document prepared for the SPs by Keck staff. But he had to escape the green room, he said, to get into character. He wandered down to his assigned classroom about 1:15.

He spent a few minutes flipping through the case materials again — wondering aloud, at one point, whether an Orthodox man would really wear a sunshine-colored yarmulke.

Then he crawled under the bedsheet and asked for the lights to be dimmed.

He closed his eyes and slowed his breathing. He imagined being in his home and what it might feel like to know that his life was almost over.

"You don't worry about paying the bills — there's a relief in that," he said later, describing what he thought about in the moments before the exercise began.

By the time six students walked in 20 minutes later, David Solomon seemed to be asleep.

SPs often talk about a "Seinfeld" episode in which Cosmo Kramer, played by Michael Richards, takes an acting job at a medical school.

Disappointed that the ailment he will portray isn't bacterial meningitis, "the 'Hamlet' of diseases," he throws himself instead into playing a patient with gonorrhea.

Students Ali Shannon Philander, left, and Jennifer Sakioka after treating a hospice patient portrayed by actor Bob Rumnock. More photos

"I burned for her, much like the burning during urination that I would experience soon afterward," Kramer tells a group of med students as he sits on an exam table, a cigarette held rakishly between two fingers.

In real life, "going rogue," as Rumnock calls it, doesn't fly. There's no room for "actor-y" shtick that gets in the way of learning.

Rumnock recalled one performer who insisted that a belligerent, backache-suffering character would never climb onto a stretcher.

"I mean, really," Rumnock said. "How is the class supposed to talk with him when he's lying on the floor?"

Working as David Solomon at Keck, Rumnock tuned his performance in response to the students.

When he sensed discomfort in one, he dialed up the emotion — his face turning red, tears forming in his eyes.

It forced the student to engage, laying a hand on Rumnock's shoulder.

"I felt you connect with me and then pull back," he later told the students as a group, during a feedback session after the exercise. "I felt, 'I can't let this happen.'"

Class member Stephen Kessler said he had trouble keeping his composure while working with Rumnock, even though he knew the actor wasn't actually dying.

"It's funny. You're sitting in a room that is obviously not a hospital room — it's a room on campus that you've been to a bunch of times before. But it does feel real," Kessler said. "A lot of credit goes to the actors. They throw themselves into the characters they're supposed to be playing."

One week after playing David Solomon, Rumnock was rushing back and forth between work on an independent movie and another SP gig at Keck.

This time, he would portray an angry patient.

It's a rare opportunity to do improv without comedy. Everything that defines acting is here."— Bob Rumnock, actor

"It's a great acting exercise," he said. "It's a rare opportunity to do improv without comedy. Everything that defines acting is here" — complicated emotions, physicality, give and take.

But for Rumnock, as for the students, there's also more: a collision between performance and reality that surprises him.

Being an SP has awakened his inner hypochondriac: "Every time I do a diabetic," he said, "I'm convinced I have diabetes."

It has also changed how he regards the doctors he comes across in his own life. When a cousin was recently hospitalized, gravely ill with liver failure, Rumnock watched a physician stumble through a discussion of her care.

The doctor talked and talked, but it was clear to Rumnock that his cousin didn't understand that she was dying — and that the doctor didn't grasp that.

"We are so isolated," Rumnock reflected. "We don't know how to communicate anymore."

At his cousin's side, he started asking questions that steered the doctor toward spelling out the truth.

He tried to do it gently, the way the best medical students learn to do.

Follow Eryn Brown (@LATerynbrown) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Bachelors Ball is L.A.'s revel without a cause

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.