Great Read: Years pass, but couple’s commitment to skid row hasn’t wavered

The draft dodger is 68. The ex-nun nears 80. But on a cold early morning in March, they have trundled to a street corner for their regular trip passing out donated pastries to men and women who sleep near the Los Angeles River and underneath its bridges.

At the corner, they are confronted by several typed sheets of paper plastered to a utility box. “Homeless guy, go away, you are not welcome here,” the sheets read. “We don’t pay thousands of dollars in rent every month so that you can have a nice, safe place to squat.”

It’s nothing new. Jeff Dietrich and Catherine Morris — who defied society by getting married and haven’t stopped slinging arrows at the status quo since — have drawn constant criticism during their four decades of work on skid row.

“We’re known as the homeless enablers,” says Dietrich, who has a distance runner’s wiry frame, flowing gray hair and the kind of intense certainty that wins followers but also enemies. “Yes, we believe in enabling people living on the streets, people who’ve been discarded by society, so they can live with as much dignity as possible. I guess that’s right, homeless enablers is what we are.”

When their journey began, the revitalization spreading beneath the downtown skyline was only a dream. But skid row was filled with the same desperation.

The goal is to be a witness to suffering and injustice, and try to help.

— Catherine Morris

It was the early 1970s, and they joined the small but burgeoning Los Angeles branch of the Catholic Worker, a lay organization started in post-Depression New York by radical Catholic pacifists who sought adherence to the Gospel by living in poverty and aiding the downtrodden.

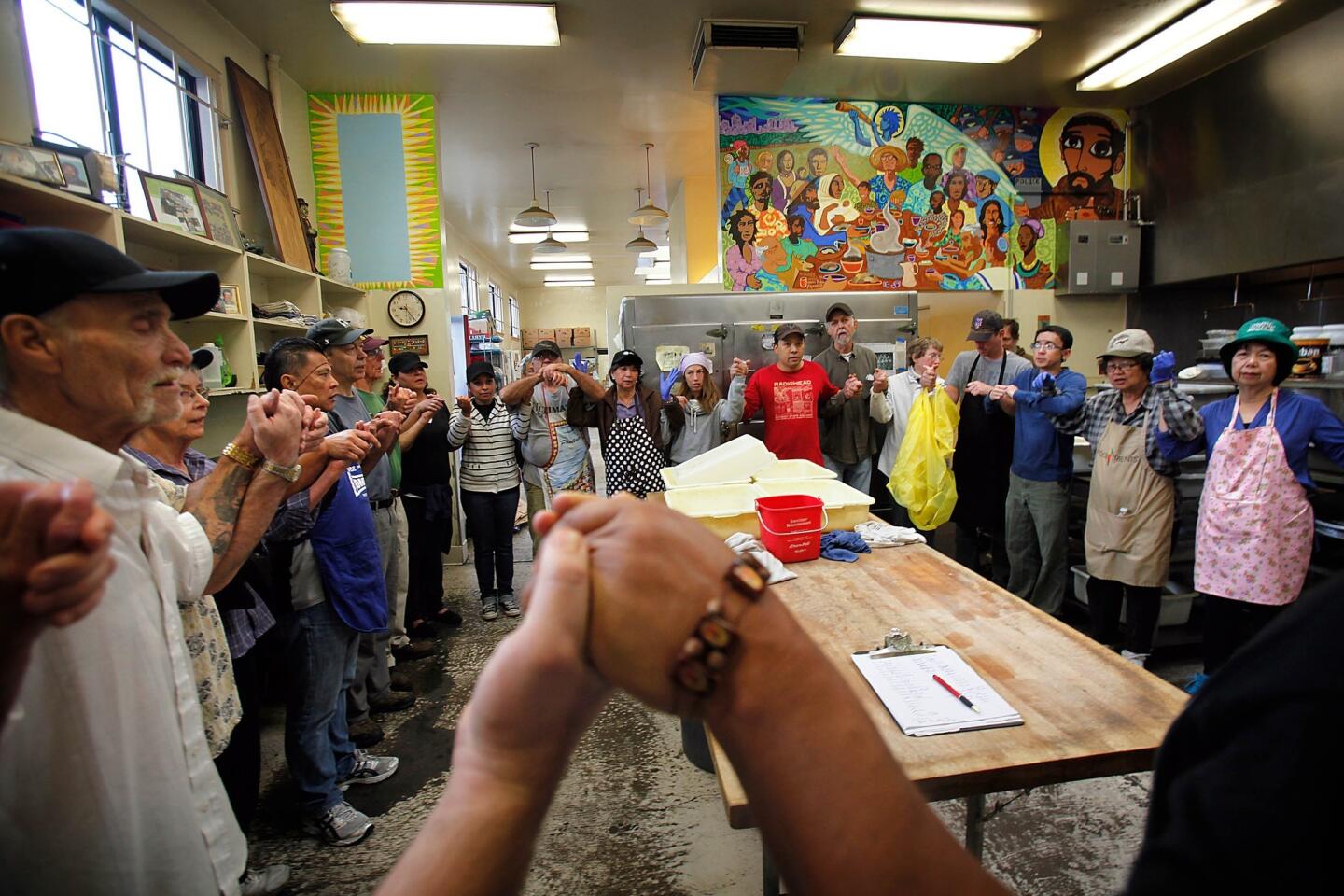

Today, from a cramped 6th Street cookery — an outpost known as the Hippie Kitchen — lines on some days stretch long down the sidewalk and the couple lead a crew doling out 5,000 plates of hot food each week.

They have plenty of critics, usually people who believe the couple are hindering downtown’s progress by making life easier for the homeless. Sometimes, though, the naysayers are other activists — or even the hierarchy of their own Catholic Church. (Among their fondest memories: stopping a 1990s groundbreaking for downtown’s cathedral by hijacking an earthmover that then-Archbishop Roger Mahony planned to use for the ceremony.)

“We’re happy being the no-sayers,” Morris says, “running in opposition to the way things usually work.”

They are so anti-establishment that they don’t accept government aid, even though they could use the help. Believing that the police enforce unjust laws, they steer clear of calling the cops, even when they have been attacked by their clientele.

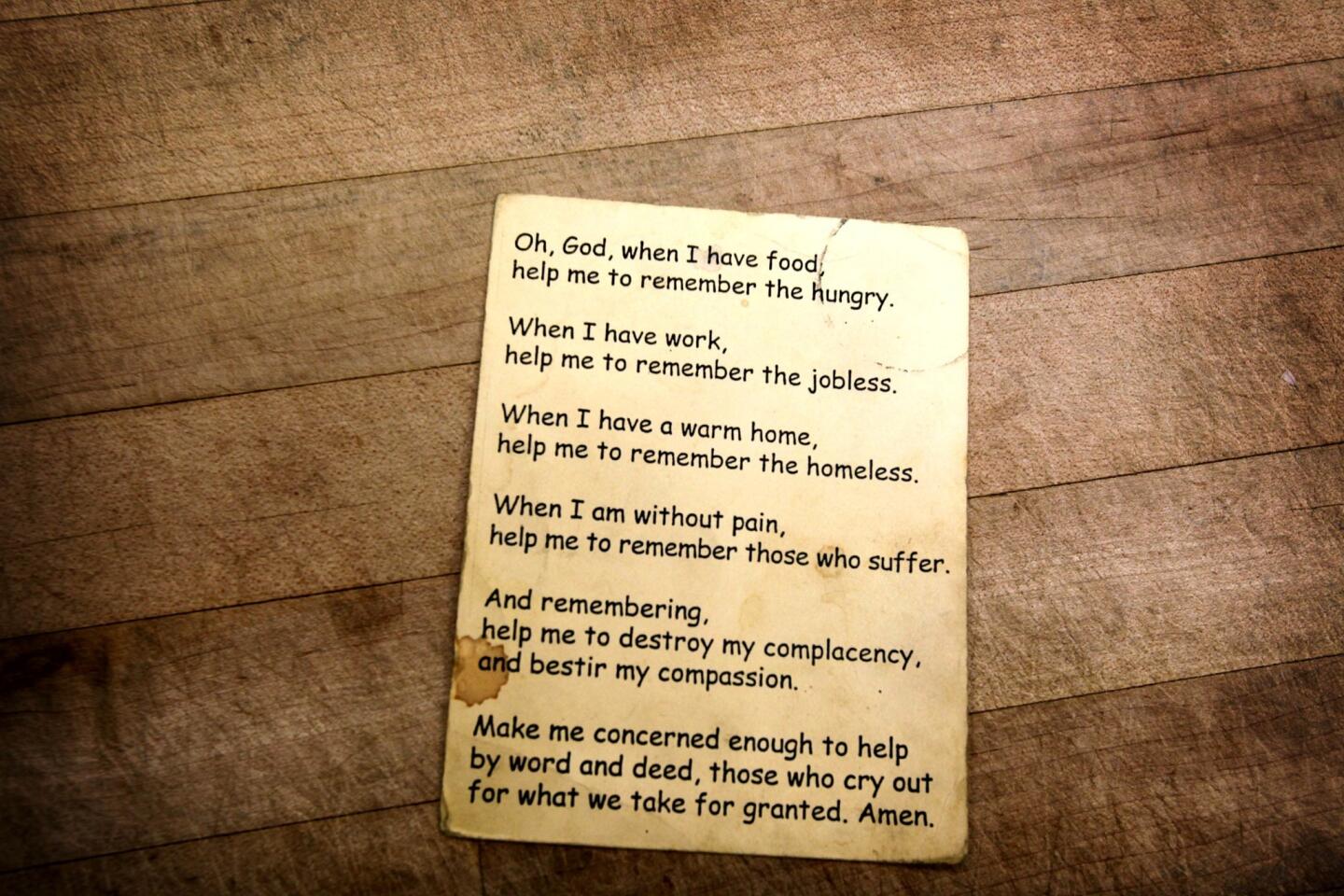

They don’t preach, proselytize, seek converts or hand out Bibles. They tend to pray in public only while protesting, which they do most often at the steps of downtown’s federal building, beseeching God’s forgiveness for America’s militarism. Few passing on foot or in cars notice them, or the handful of Catholic Workers lining up with them.

“Recognition isn’t important,” says Morris, a forceful woman with a quick wit and grandmotherly touch, though she has no children. “The goal is to be a witness to suffering and injustice, and try to help.”

She’s sitting on a stool on the Hippie Kitchen’s garden patio, watching, eagle-eyed, as dozens of hungry people devour plates of salad. When one woman ambles up, Morris reminds her to stay safe on the streets and then gently kisses her swollen, bruised, dirt-caked hands.

It is this kind of steadfast love that has inspired observers like Father Tom Rausch, a Jesuit priest and professor at Loyola Marymount, to compare their work to that espoused by Pope Francis, who has called on his church and its faithful to focus more on helping the poor.

“I think finally we have a pope in line with the Catholic Workers,” Rausch says. “If he were a simple priest living in Los Angeles, he’d be with them. Times have changed. There’s a sense that the work they are doing is validated by Francis, that he is saying the kinds of things they have been saying for years, and that has to feel very good to them.”

::

They met at the Hippie Kitchen, which was started by Catholic Workers out of a beaten van in 1970.

She was a nun, taking a year off from being the principal at Pasadena’s wealthy Mayfield Senior School to work with society’s castoffs.

He was a self-described “long-haired hippie with an aversion to authority” — an iconoclast who had been an altar boy, raised by conservative Catholic parents in Fullerton. After college, he refused induction during the Vietnam War and headed to Europe, assuming he would be arrested upon his return. (“I consider myself a draft resister,” he says, “not a dodger.”) When he wasn’t, he joined the Catholic Worker, admiring the progressive vision of Christian social justice.

Soon enough, Dietrich and Morris were in love and she was leaving the Sisters of the Holy Child Jesus for him. In 1974 they married, deciding that together, with his outspoken charisma and her organizing skill, they would devote their lives to skid row, leading the Catholic Worker’s Los Angeles chapter.

Then as now, the movement was spread thinly across the country, operating out of so-called “hospitality houses,” mostly in urban neighborhoods. Then as now, the house in L.A., on a rough street in Boyle Heights, was a rickety old Victorian donated to the cause. Shared by up to 30 workers, it was kept threadbare to increase the sense of being poor, and because what little money that trickled in from donations went almost exclusively to food for skid row.

The Catholic Worker movement has always held that society is trapped by misguided priorities that make the problem of homelessness worse. So Dietrich and Morris railed against any institution they felt ran contrary to Christ’s teachings. They protested nuclear arms, blockaded Army recruitment centers, spilled blood and oil on the steps of the federal building before the first Gulf War. (Asked how many times they have been arrested, they say more than 40 but note that they can’t be entirely sure because they have stopped counting.)

Few felt their sting more directly than the Catholic Church, especially its hierarchy, which they long regarded as ossified and out of touch. In the 1990s, they took the Los Angeles Archdiocese’s decision to spend $200 million on the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels complex as an affront to the society’s down and out.

Leading a small band of fellow workers and like-minded supporters, they stormed the old archdiocese, St. Vibiana’s Cathedral, unfurling a banner from the bell tower that read, “We Reclaim the Church for the Poor.” When Mahony held the groundbreaking ceremony for the new cathedral, they scaled a fence, tussled with a priest and commandeered the earthmover.

“It was as much excitement as we’ve ever had,” Morris says. “A little scary too.”

Mahony took to the pages of The Times, writing a commentary noting that although there was room in the church for the Catholic Workers, the group had “shortchanged the poor when they adopt the stance that the church should be attentive only to the material needs of the needy.” Mahony didn’t respond when asked through a church spokeswoman to comment on Dietrich and Morris.

Downtown business leaders are similarly tight-lipped about the couple, especially after a judge ruled in 2012 that shopping carts given to the homeless by the Catholic Workers — as ad hoc mobile storage — couldn’t be confiscated. The ruling was viewed as a blow to revitalization efforts by some who view the carts as contributing to blight.

Even other homeless advocates on skid row are wary.

“My ears are still ringing from the time Jeff interrupted that press conference,” says the Rev. Andy Bales, chief executive of the Union Rescue Mission, recalling a 2010 news conference when police hoped to announce an injunction banning scores of drug dealers from skid row. To Bales’ chagrin, Dietrich and the other workers disrupted the event with a loud protest.

“I love the work they do helping, such as the soup kitchen,” says Bales, whose $29-million, 225,000-square-foot mission is the largest on skid row. “But they are at times naive about the people they help. Sometimes they end up protecting people who prey on addicts.”

Dietrich begs his critics off, sometimes countering them in his writings for the Catholic Agitator, a Worker newspaper he edits.

“All you have to do,” he says, “is read the Gospels and see what happened to Jesus. He got crucified We’re in good company.”

::

For the most part, the homeless they help are extremely thankful for the workers. “I would be dead without the hippies,” says a woman sitting on a bench outside the soup kitchen. She won’t give her name because she has AIDS and fears being beaten on the streets if word of her illness were in a newspaper. “How can I not love these people?”

Still, danger always lurks. Dietrich has been spat upon, threatened with knives and knocked out by a stiff punch. Morris recently had to confront a man menacing the soup line with a piece of wood that looked like a bat.

And time is having its way, making the work more difficult. Dietrich walks with a limp, and on occasion his back locks up. This month, Morris will be 80. She is full of enough energy that she recently drove to Nevada and protested the use of drones outside a military base. But she is also growing stooped; arthritis gnaws at her legs, and she spends as much time as possible sitting.

These days, a hard question is often asked at the Hippie Kitchen: What will happen when Dietrich and Morris are gone?

Only 12 workers still live in the old Victorian. Half are older than 50. They don’t want the burden of taking over. The younger ones simply aren’t ready and may never be.

Dietrich notes that there was a time when he and his wife worried ceaselessly about finding the right successor. But they have given up.

“If God wants this to continue, this will continue. That’s how we have come to view it because we’ve had to,” he says. “Hopefully, the spirit will guide this community when we are gone, but the spirit moves the way She will.”

He wipes sweat from his eyes and looks out at the Hippie Kitchen garden. A barefoot woman dressed in a bathrobe argues about Kobe Bryant. A young couple hug and hold hands. Men in tattered Army overcoats sit underneath a jacaranda tree, playing chess, plotting their next moves.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.