Jerry Brown ready to commit to a rainy-day fund

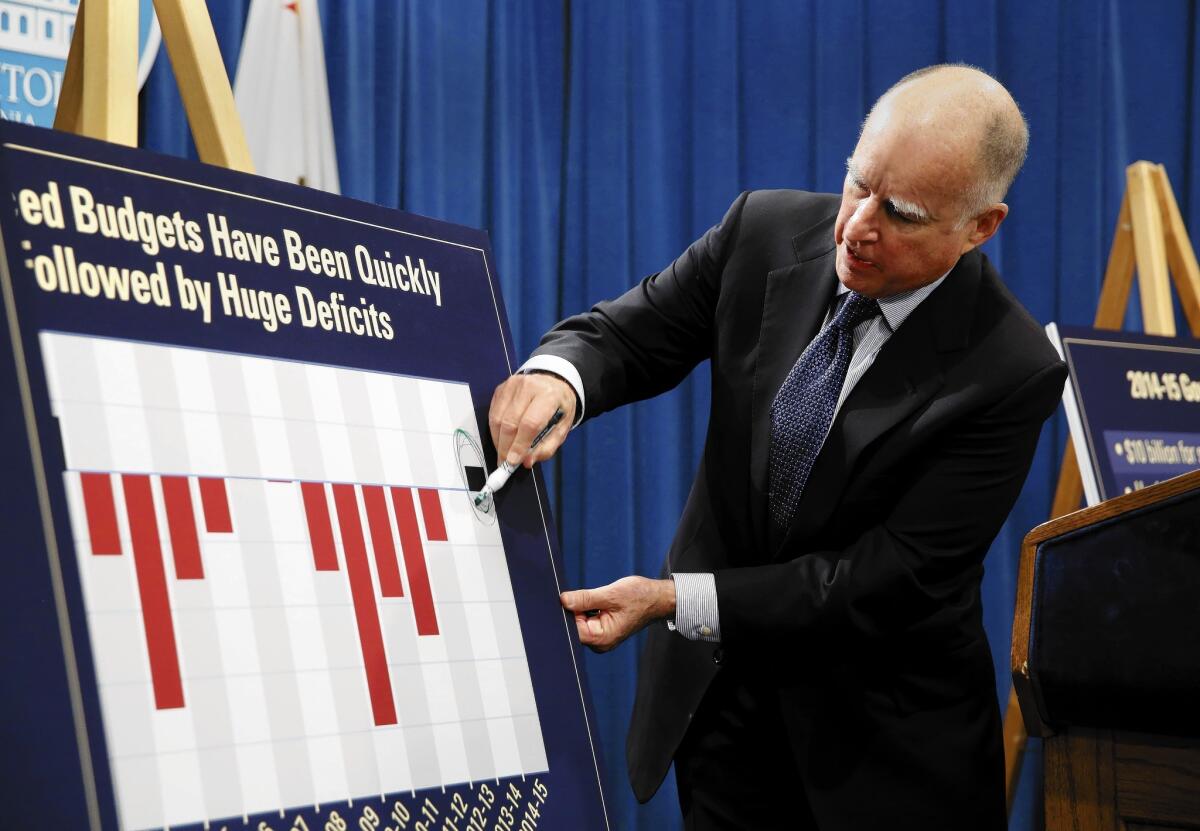

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Jerry Brown stepped out from behind the podium holding a green marker, ready to assume the role of professor.

As he laid out his new budget plan, he circled the spot on a chart showing California’s budding surplus. Some people think “we should go on a spending binge,” he said.

He wouldn’t do that, Brown said: “We see the lessons of history.”

If anyone in the Capitol knows California history, it’s the 75-year-old governor serving his second stint in office. On his watch, recent deficits have disappeared amid a combination of budget cuts, tax hikes and economic luck.

However, other deep-rooted financial problems remain unresolved: big bills for teacher pensions, rising healthcare costs, a volatile tax system that can leave officials with whiplash. Brown has only begun to address some of these issues.

In the coming months, the governor will negotiate a final budget with a Legislature dominated by Democrats, who may be eager to expand social services and education programs in an election year.

In that process, Brown will have to avoid the mistakes of the 1990s, when California’s situation was remarkably similar to today’s — a flood of tax receipts, a hunger for new spending and a budget crisis rapidly fading in the rearview mirror.

Back then, the state’s leaders decided, “Hallelujah, let’s spend,” Brown said Thursday when he announced his budget. Reforms were abandoned, and the state rushed headlong into the dot-com bubble, which was followed by the housing bubble, then the stock market crash and years of financial turmoil.

Steve Levy, director of the Center for Continuing Study of the California Economy in Palo Alto, said it would be tempting for Sacramento to put off addressing long-term financial problems. But “this is a time when we can really get our budget house in order,” he said.

On Thursday, Brown hoisted a poster detailing the state’s far-reaching obligations, and they totaled $354.5 billion, more than twice the spending in his one-year budget proposal.

His budget would chip away at some of those expenses. For example, his administration calculates $64.6 billion in overdue maintenance for roads, schools, parks and other public facilities. Brown’s proposal would provide $815 million.

He also wants to use the state’s projected surplus to accelerate his assault on California’s “wall of debt” — $24.9 billion in loans and deferred payments racked up while the state was struggling through multiple budget crises.

Brown’s proposal would chop that sum nearly in half by the middle of next year and eliminate it in 2018. Certain payments to schools would no longer be delayed, a major turning point after years of pink slips for teachers.

But on other issues, the future is less clear.

The teacher pension fund is lacking about $80.4 billion, and state officials estimate it would cost $4.5 billion a year to stabilize the system. That’s the same amount Brown wants to spend on all of the state’s natural resources programs in the next fiscal year, which begins July 1.

Brown said the solution involves bigger contributions from the state, school districts and teachers. That will require election-year negotiations with the powerful California Teachers Assn., which has been closely allied with the governor.

A spokeswoman for the union, Claudia Briggs, said the group was open to increasing teachers’ share of the cost.

“It’s going to be daunting; it has to be done,” Brown said. “Sometimes it’s hard to get things done until people really see the disaster ahead.”

Preparing for financial disaster has not been California’s strength.

When the state emerged from the recession of the early 1990s, Gov. Pete Wilson convened a blue-ribbon commission to find ways to limit future financial problems. The panel’s recommendations, including more stringent requirements for balancing the budget, went nowhere.

But the economy came roaring back, flooding the state with new tax money. Spending increased under Wilson, who nevertheless left his successor, Gray Davis, a $10-billion surplus. Davis pumped more money into social services, education programs and benefits for public employees.

Money wasn’t being saved for a rainy day. The state was hit hard when the dot-com bubble burst, revenue from income taxes evaporated and an expensive energy crisis emerged. California soon had a $38-billion deficit.

Davis’ successor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, created a commission to reevaluate California’s tax structure. Its recommendations stalled when Democrats complained that they amounted to a tax cut for the wealthy.

Today, generous promises made to state workers still weigh on California’s budget. The Brown administration estimates that healthcare costs for those retirees over the next 30 years will be $63.8 billion more than the state has set aside.

The governor does not suggest any fixes to the system in his latest budget proposal, but the document assumes salaries will increase by $357 million. That’s partly because of a planned 2% pay hike for most state workers, agreed upon last year.

Brown acknowledged last week that California’s budget remains unstable and surpluses can quickly crater into deficits.

“What goes up,” he said, “just as sharply goes down.”

California relies heavily on taxing the wealthy, who derive much of their income from the stock market, which is notoriously unpredictable.

The top 1% of income earners paid 41% of the income taxes in 2011, according to the most recent state statistics. The proportion is probably larger now because voters in 2012 approved a tax hike on high earners.

Brown wants a ballot measure this year that would capture surges in revenue and save them for a future economic downturn. Many other states have used reserves as a buffer against recessions, but California has lacked such a cushion.

The governor said he’s willing to make a down payment on a reserve fund of $1.6 billion in the next budget. Top lawmakers have also emphasized the need to stockpile cash.

Fred Silva, who helped write the recommendations that were ignored in the ‘90s, said he sees legislative support as evidence that the state is ready to turn the corner.

Two decades ago, he said, “there was virtually no discussion about building reserves, even though we were coming out of a very difficult period.”

He added, “This time, the discussion has been much different.”

mes.com”>[email protected]

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.