A Lincoln Heights fixer-upper is transformed into a country escape in urban L.A.

THE classified ad caught Ilse Ackerman’s eye: “Lincoln Heights Fixer-Upper. Artist Vision Required. On cul-de-sac.” No address was listed.

Intrigued -- and determined -- she and husband Meeno Peluce drove to every cul-de-sac in the area in search of “For Sale by Owner” signs. When the couple finally saw the 1926 house -- atop a steep, winding dirt road on the outskirts of downtown Los Angeles -- they found a condemned structure. The backyard featured a discarded black Naugahyde couch and some yucca plants. Everything else was dead.

Ackerman and Peluce, however, were not deterred.

“We didn’t see it as a wreck,” Ackerman remembers. “It always looked like it does in our minds.”

In their minds, they saw a magical outdoor space for their growing family. After six years of the couple’s planting, transplanting, building and tending, visitors can see it too: a wild jungle of blooming Pride of Madeira, cascading white roses, flowering bougainvillea reaching toward the sky. Thriving vegetable gardens are filled with chard, squash, tomatoes, basil and sunflowers, some bursting from simple bales of hay and compost with eye-popping color.

Then there are the animals of Skyfarm, as the couple has dubbed their home. Two dogs, three cats, one tortoise. A couple of cockatiels in an aviary, six chickens in a coop, a pet squirrel with the Spanish name Quince -- “because he is the 15th animal,” Peluce says. And that’s not counting the 60,000 to 90,000 bees in three hives kept by Ackerman, a sculptor and former art teacher turned amateur beekeeper.

For her, Skyfarm is where her creative energy takes flight. For Peluce, a professional photographer, it is his “decompression chamber” -- a country escape in the heart of urban L.A.

At the time Ackerman saw the classified ad, the couple was living in a loft at the Brewery industrial arts complex near downtown and were looking for an affordable house with more room. Ackerman, a New England native, pined for a garden.

They hired an inspector to look at the Lincoln Heights house, and his assessment was grim. “He assumed it was a tear-down,” Peluce says. “He also told me the house was ‘a marriage breaker.’ But for us, it was just another adventure.”

They purchased the property, their first home, in October, and moved in by December. The house was barely inhabitable, with holes in the wall, buckled floors and no hot water. Enough debris had been dumped on the property to fill the equivalent of eight railroad cars. Undaunted, the couple cooked meals on a camp stove, prompting them to call this period their “homesteading” phase.

Friends and family thought they were nuts.

“I was terrified,” says Sondra Peluce, Meeno’s mother, remembering her first impression of the house. “I thought they had taken leave of their senses. I actually think I went and threw up. It was like an out-of-control fun house that was not fun.”

Her dismay turned to pride, however, as she watched the home’s transformation over the succeeding months.

“When I saw my son hoisting railroad ties on his shoulder, I thought to myself, ‘He is building an inner strength that will carry his family forever,’ ” she says.

By his own admission, Peluce was not a handy guy. A former actor and now a photographer who has shot album covers for the likes of pop R&B singers Rihanna and Mary J. Blige, Peluce had no background in home and garden renovation. Indeed, he and his wife now laugh at his Sharper Image “upscale gentleman’s tool kit,” which now hangs in their pantry as decoration.

But that didn’t keep him from working alongside the builder he hired. As they began excavating, remnants of the home’s colorful past and its original owner emerged.

“You could see there was a pond and workings of different fountains,” Ackerman says. “It was like a neglected plantation.”

As the couple added plants and animals, the ambience became decidedly more rural.

“We live in the country in the city” is how Peluce describes life at the end of a dirt road.

Like most things on Skyfarm, the eclectic mix of plants includes the salvaged and repurposed. (“I’m addicted to thrift,” Ackerman admits.) When they read in the Recycler that an old grove of bamboo was to be torn down in Bell Gardens, they rented a flatbed truck, dug up the trees and replanted them here.

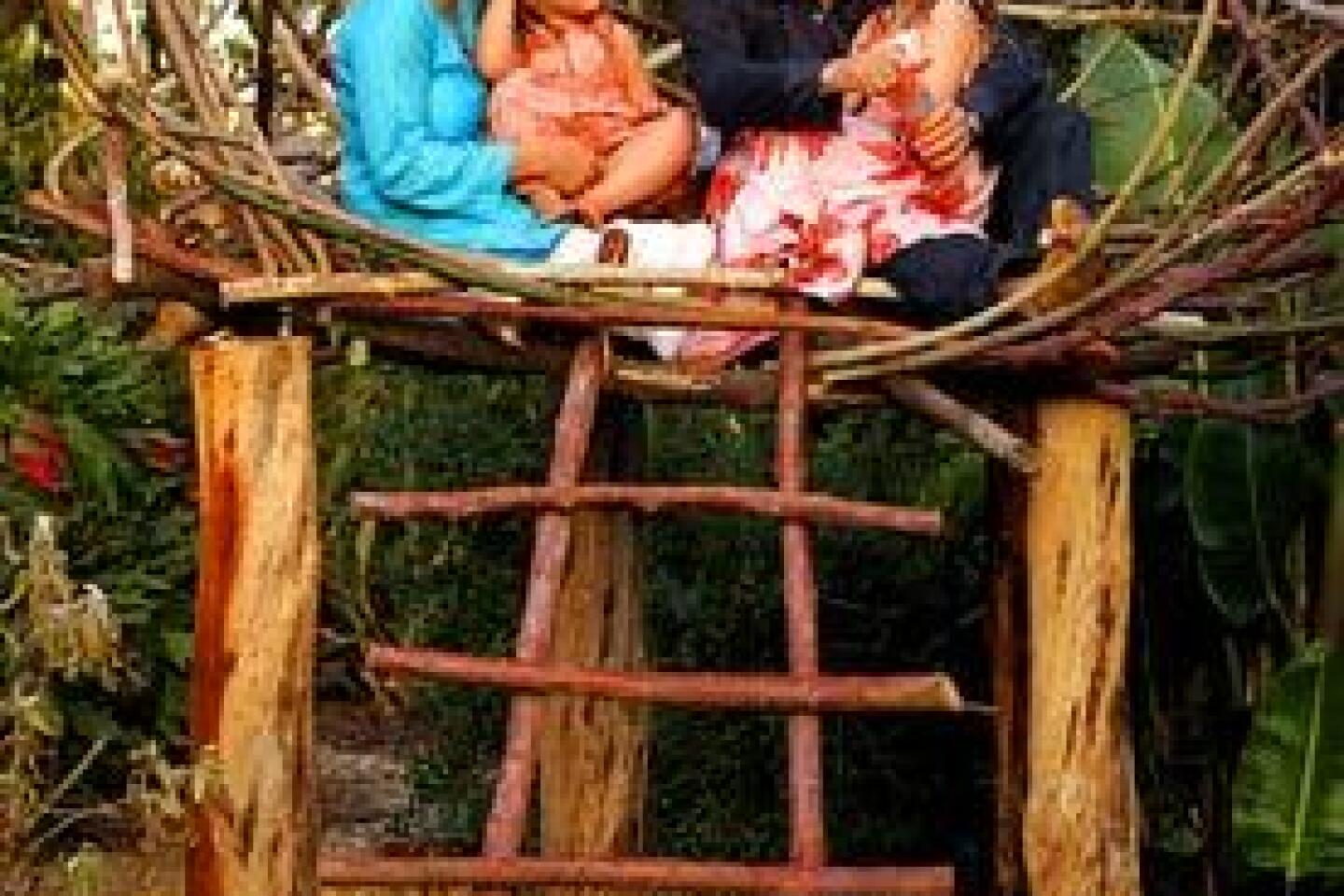

The New England farmhouse they envisioned allows daughters India, 7, and Mette, 3, to move freely between the colorful, art-filled interiors of their home -- a style their parents have dubbed “Cowboy Craftsman” -- to the oasis outside. Fanciful, hand-laid footpaths lead to an outdoor dining area, a barbecue, a hot tub they found in the Recycler for $100 and the animal pens.

Asked what prompted her interest in beekeeping, Ackerman could not recall. She does, however, remember buying a copy of “Beekeeping for Dummies,” recommended by an East L.A. supplier of beekeeping equipment. But she is among the growing number of people concerned about Colony Collapse Disorder, a mysterious affliction that has killed billions of bees worldwide.

“She is the daughter of a teacher and a philosophy professor,” says Peluce, who met Ackerman when they were both teachers at Hollywood High. “She is someone who was always taught to look things up,” he adds. The backyard collection of animals provides the children with daily lessons, a direct connection with the food cycle -- which is not always easy in an metropolitan environment. With city lights in the not-so-far-away horizon, they have established an equilibrium of urban and country, old and new.

“Climbing into ramshackle, beautiful, old falling-down places has been a big part of all our adventures leading up to this house,” Peluce says. “So when we climbed into the beat-up hulk of the old grand dame that is our home, we felt very much at home with the spirit of its decrepitude.”

Adds Ackerman: “All of our adventures make us closer. There is no way we will ever leave this house.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.