Great Read: How a transgender man tries to honor his Muslim faith

reporting from san francisco — He walked unsteadily across the tattered green carpet inside the mosque. Out of habit, he stepped for a moment toward the women’s section. Then he made his way to the front, where the men pray.

In one sense, everything felt familiar after a childhood spent in Islamic Sunday school every week: the smell of strong cologne worn by so many of the men, the low murmur of Koran recitations.

“Can they tell?” Alex Bergeron recalls asking himself as he knelt for prayer.

The sideways glances were probably innocuous. Just other men taking a fleeting moment to register the newcomer in the room. He mentally scanned his body for any gesture that might betray his secret, realizing that his arms were clenched too tightly around his body as he prayed, that his legs were held too closely together, like a woman.

The men around him didn’t know that the young Palestinian American, then 18, was reaching, almost recklessly, for a new life — and reconnecting with an old one.

Born with female anatomy, Alex had recently begun hormone therapy and decided to fully transition to a male identity. And as he entered his second adolescence, he had decided to rededicate himself to a life as a practicing Muslim. On most days, he returned three times a day for prayer.

“It felt like the missing piece,” he says.

This path he had taken was not an easy one. Perhaps, however, it would settle once and for all: Could Alex be transgender and Muslim at the same time?

::

Muslim Arabs have some history with people who hold a culturally recognized third gender, including eunuchs who lived in the time of the prophet Muhammad and came into contact with him. But not in the modern period.

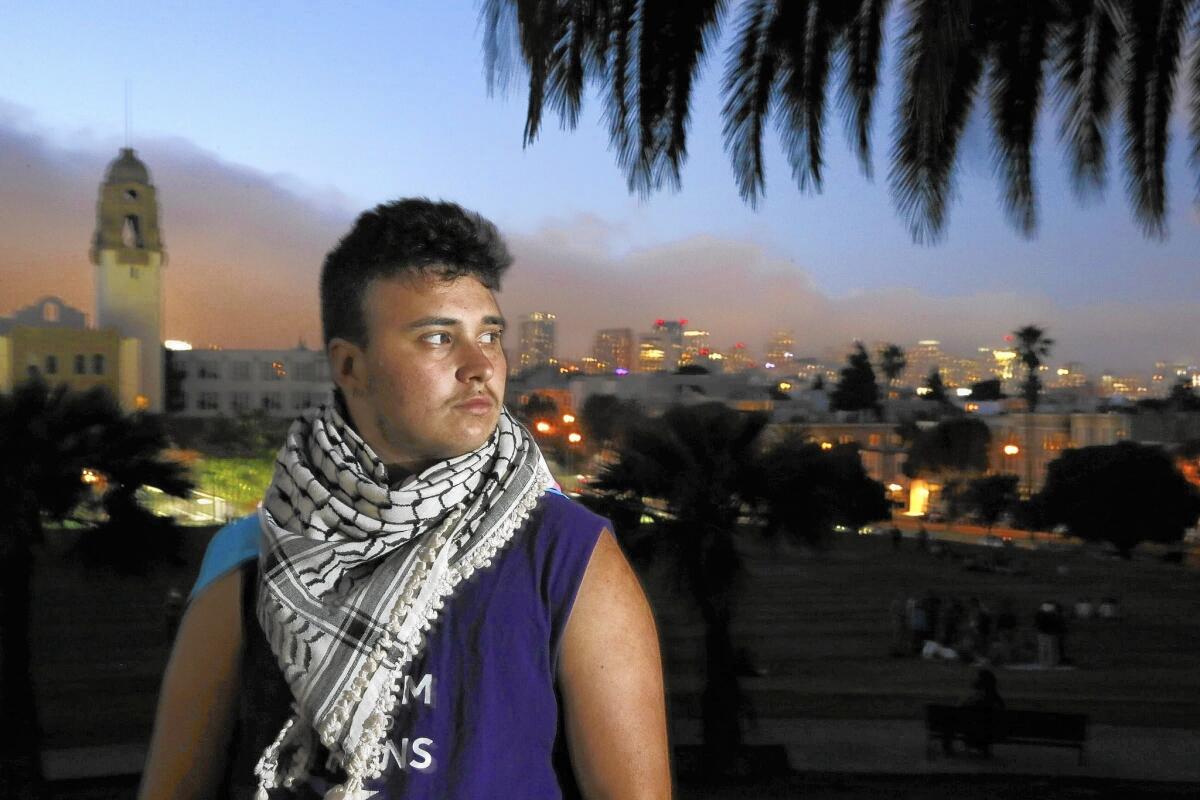

Alex deliberately chose a gender-neutral name and prefers to be called “they” instead of “he” to indicate that gender identity is not just a male/female binary but a continuum along which any individual may fall — and where Alex occupies a middle space. The 20-year-old gets tongue-tied with it at times and reverts to the more convenient “he.”

Perhaps no identity in Islam is harder, Alex thinks, than a person with female anatomy who wants to transition to life as a man.

Alex is aware of media reports that naively heralded Iran as an affirming place for transgender people in the wake of the 1987 decision by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini allowing gender-reassignment surgery. Iran is now the second-largest center for the procedure behind Thailand, according to some estimates.

Alex has also heard about a similar religious ruling by clerics at Al Azhar University, the leading institution of Islamic thought in Cairo.

“Those decisions just allow them to ‘fix’ people and say that they don’t have gay people,” Alex says. “It’s because they are so conservative, not because they are liberal in any way. They would never allow someone like me: a trans man who is sexually attracted to men and women and trans men and trans women.”

And in America, mosques tend to be conservative, and visits to the local imam or mosque committee chairman usually draw stern rebukes for LGBTQ Muslims.

Small, progressive Muslim organizations exist in some major cities, and there is an annual LGBTQ Muslim spirituality retreat held each year on the East Coast.

“That’s really all there is,” says Scott Siraj Haqq Kugle, a professor at Emory University who has written extensively about transgender issues and homosexuality in Islam. “No dates or location are publicly disclosed because there must be a lot of secrecy to keep it as a safe venue. It’s very delicate.”

Still, maybe, somehow, Alex believed there was a way that Islam would help ease the bewilderment of his situation, providing his life with structure and meaning.

::

Over potato tacos at Gracias Madre, a chic vegan Mexican restaurant in the Mission District, Alex prepared for what he worried might be a hard conversation with his grandmother.

“I have something to say, and I don’t know how to say it, but I need to say it,” Alex recalls telling her.

“I think I joked, ‘What, you want to be a man?’ And when the answer was ‘yes,’ I understood, because I once did too,” Jazmine Bergeron, 60, says.

Jazmine, whose mother was Japanese and father was a French Jew, dated girls in her teens and briefly considered living as a man when she turned 13. Instead, she married a devout Muslim man when she was 19 and gave birth to Alex’s mother, Sugako, at 20.

When Jazmine separated from her husband a year later, she says he used her sexual orientation to persuade social workers that he should have full custody of Sugako.

Jazmine went on to become a prominent activist for multiracial Asian lesbians in San Francisco, and she was estranged from Sugako, who reached adulthood fully covered by a niqab, with just an opening for her eyes. Pictures of Alex as a child show a little girl with a gap-toothed grin framed by her hijab.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, Sugako and Alex were at a Walgreens in Oakland when a security guard reportedly harassed her as “the bride of Bin Laden.”

The case drew outrage from the American Civil Liberties Union, and Sugako experienced a political awakening that led her to participate in many protests.

“I come from a long line of activists,” Alex says. “We each had our own very different fight.”

Alex was forced out of the family home at 15 after coming out as a lesbian. Homelessness, meth addiction and deep depression followed.

Forty-one percent of transgender or gender-nonconforming people attempt suicide, compared with only 1.6% of the general population, according to a 2011 survey by the National Center for Transgender Equality.

Alex knew these statistics yet decided that living as a woman would bring even deeper turmoil. The smiles of childhood fell away to a more melancholy young man whose photographs captured him more deliberately constructing an identity piece by piece, with cropped hair, a hoop piercing his eyebrow and a metal stud embedded in the middle of his upper lip.

Sugako wrote notes to Alex’s connections on Facebook to call this new life a lie and a “science experiment” gone awry.

“No matter what,” Alex says, “I still love her. That’s my mother. I have to thank her for a lot of what I’ve done in my life now.”

But Alex had the support of one family member, at least: Jazmine.

“The one thing I said, and this is so unpolitically correct, was: ‘Well, if you’re going to be a man, you’re going to be a good man,’” Jazmine says, “because as a lesbian I am so sick and tired of these 5-foot-tall trans men. I am taller than them. I am bitchier and stronger than they are. But I looked at Alex, and I said, ‘You’re tall, you’re strong.’ ”

::

Alex sometimes envies the path of his best friend, Zaki Hale, who is also Palestinian American.

“My cousin told me you can’t be gay and Muslim, so I just said, ‘I’d much rather be gay,’” Zaki told Alex.

Zaki, 22, has never looked back.

“I,” Alex says, “always question myself three times about even small decisions.”

For him, it is no easier to shed his faith than his gender and sexuality.

He knew there would be days when worries over his body image would prevent him from even leaving his apartment. On Facebook this summer, he typed that he was searching for “anyone who has time just to help me just get out the house without crying. I’m reaching out cuz I need help.”

But to his surprise, the struggle to reconcile his identity has brought moments of exhilaration as well.

At San Francisco’s Pride Parade this year, he drew loud cheers as he marched wearing the trans flag on his back as a cape and his father’s kaffiyeh hanging from his neck. On his arm, he showed off his tattoo of the Arabic word for strength.

When friends greeted him on the street, he exuberantly lifted his shirt to show off his hairy belly and newly flattened chest, just two weeks past breast-removal surgery.

And in the West Hollywood Pride Parade this year, he sat on the back seat of a convertible along with the two other recipients of a $10,000 youth courage award from the foundation of Colin Higgins, who wrote “Harold and Maude” and directed “9 to 5.”

Hajra Khan, his case manager at Larkin Street, a charity that provides housing and other services for transgender youth, wrote him a nomination letter for the prize.

“No matter what life throws his way, he pushes through and becomes stronger for it,” the letter said.

Alex is studying psychology at City College of San Francisco. “Because, you know, of my past,” he said. “I like working out what is the difference between persuasion and manipulation and figuring out where that manipulation is really rooted.”

But the acclaim coincided with a quiet realization that maybe he wasn’t too far off from Zaki’s conclusion that you couldn’t be Muslim and LGBTQ. So, in frustration, he stopped going to the mosque.

“I can’t be myself there,” he says. “I thought it would be the missing piece, but it was actually learning to be comfortable with myself. It wasn’t that I needed to go somewhere.”

Alex prays on his own now, studying the Koran to work out what it really seems to say about gender and sexuality.

Yet he fantasizes about attending Eid festivities in Oakland next year where his mother celebrates. “She can’t deny me when I’m right there in front of her friends,” he says.

But it now feels like the hardest fight is in the past, not the future.

“When your mother hurts you, no one can hurt you as much as that,” he says. “My strength comes from that.”

Follow @gtherolf

MORE GREAT READS:

A Texas nun greets detained immigrants at the gate to freedom

In Calexico, former LAPD official finds a police department in turmoil

India test cheating stirs outrage — then people start dying

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.