Great Read: Desert cities Lancaster and Palmdale are a prickly pair

Avenue M splits the Antelope Valley into two nearly indistinguishable swaths of desert, a concrete ribbon that roughly marks the border between the cities of Palmdale and Lancaster.

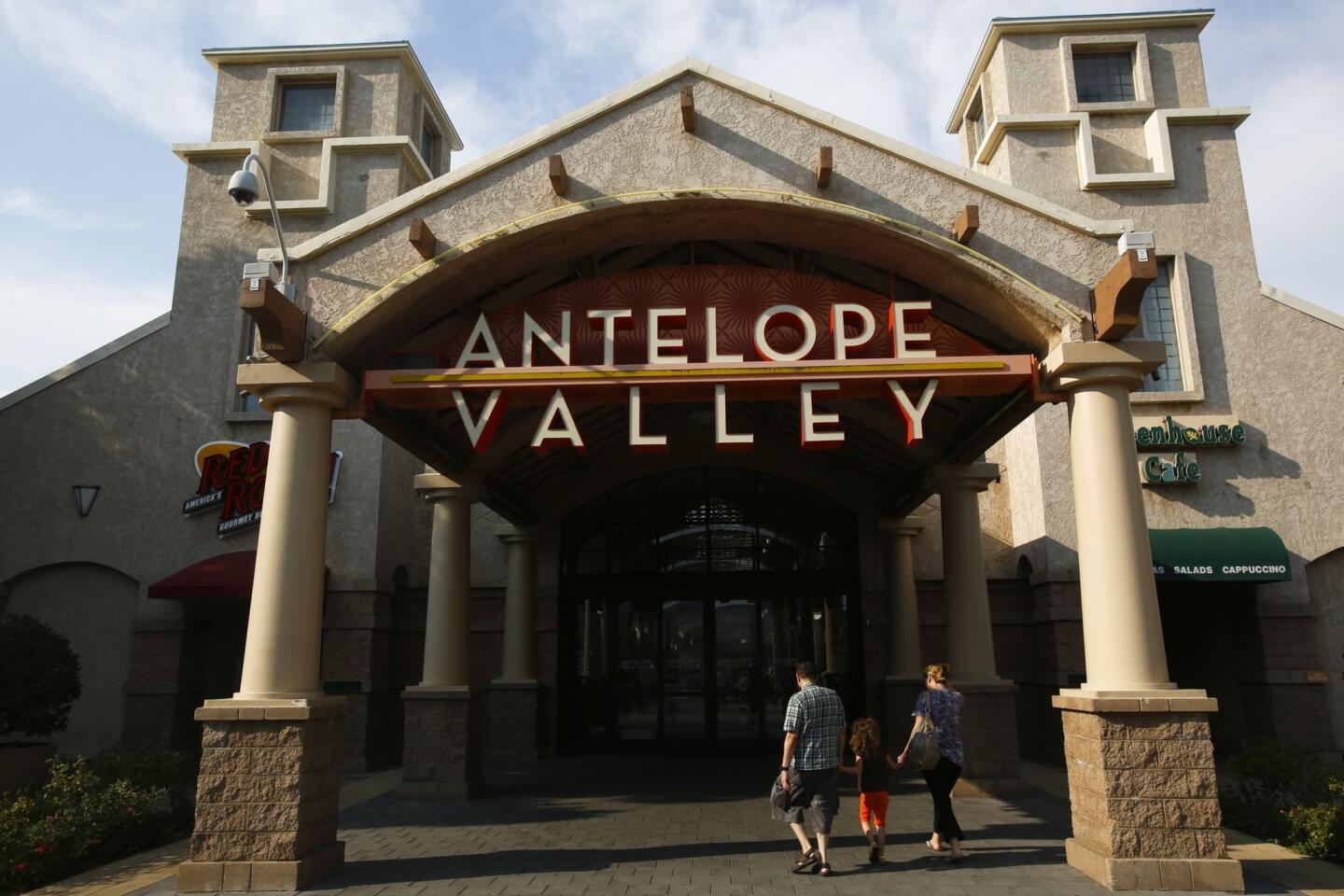

Lancaster residents head south to Palmdale’s Antelope Valley Mall, the only indoor shopping mall for 40 miles. Palmdale residents drive north to buy produce from Lancaster’s farmers market and attend the annual Antelope Valley Fair.

But for decades, some city officials have treated Avenue M as a battle line. For as long as anyone can remember, the two cities have gone to war over Wal-Marts, Costcos, car dealerships and, now, a power plant. The squabbles have cost millions, launched lawsuits and, lately, tended toward the personal.

Locals have given a name to the rivalry: the Cactus Curtain.

Relations may have reached a low point last year when Lancaster Mayor R. Rex Parris held a Chuckie doll during an interview with a local television news channel, pretending it was Palmdale Mayor Jim Ledford. For its part, Palmdale puts out a regular email newsletter that debunks what it calls Lancaster’s absurd and unsubstantiated public statements.

All of it baffles residents, business interests and many city employees. The two cities are geographically isolated, demographically identical and economically similar. Some business leaders yearn for a merger. Together, Palmdale and Lancaster would form the third-largest city in Los Angeles County and 12th-largest in California.

But the mayors of Palmdale and Lancaster haven’t shared a room for years. How could they share a government?

Both mayors acknowledge the lack of civility, and both can locate the cause: across Avenue M, in the other city.

“The curtain exists, but our side is nice and smooth,” Ledford said. “It’s their side that’s all prickly.”

“We’ve attempted to talk,” Parris said. “But they’ve given us the finger.”

No one seems to know for sure why the Cactus Curtain went up in the first place.

Some say the cities haven’t gotten along since Palmdale broke away from Lancaster and was incorporated in 1962. Others theorize that it all started with a particularly potent high school rivalry. And others point to the 1980s and early ‘90s, when a flood of new investment washed into the valley and the cities began to fight over where the money should go.

But if you’re looking for a symbol of the divide, you don’t have to look much farther than the Antelope Valley Mall, a primary engine of Palmdale’s economy. It sits on a street that features seemingly every national chain restaurant in America, a city budget officer’s fantasy of Red Lobsters, Claim Jumpers, Denny’s, Dairy Queens and other corporate businesses that are a city’s most reliable source of income.

The mall’s location was fiercely contested for years until Palmdale offered the developer millions in incentives to build on a site near the 14 Freeway in the city. The mall, which eventually lured Lancaster’s J.C. Penney and Sears, opened in 1990 and touched off a long campaign of economic warfare which, by Parris’ estimate, has cost both cities more than $100 million in lost revenue.

Palmdale built an auto mall, and soon Lancaster built a competing one. Both malls would receive millions in government aid to stay afloat, and Palmdale took over its auto mall for $6 million, according to news reports in 1993. Joint discussions for the construction of a regional theater foundered, and the Lancaster Performing Arts Center was built while Palmdale’s theater plans stalled.

Each city began offering businesses tax incentives to remain within its borders. In 1994, Lancaster gave $7.3 million in redevelopment funds to help build a Costco, and later handed over 4.5 acres of parkland to keep the big-box retailer happy, according to news accounts at the time.

A few years later, it was reported that Palmdale had agreed to refund up to $2 million in sales tax in its successful effort to lure a Dillard’s.

Former Lancaster Mayor Henry Hearns, who served on the City Council for 18 years ending in 2008, said he tried to bring the two cities together.

“When I came onto the council, everyone wanted me to pick a side on that team. But I didn’t want any part of it,” Hearns said.

He helped organize joint city council meetings to improve cooperation. Leaders organized a peace march on the anniversary of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, Hearns said. A group from each city met in the middle at Avenue M for a rally and speeches.

Hearns considers that day a high point.

“Back then we fought all the time. But it was a friendlier fight,” he said. “I don’t see how the way things are now is helpful at all.”

Parris, 61, and Ledford, 60, both grew up in Palmdale and attended Palmdale High School. The two were never friends, but they worked together as members of the Antelope Valley Republican Assembly.

Ledford was elected Palmdale’s mayor in 1992. When Parris became Lancaster’s mayor in 2008, the two agreed to a monthly lunch meeting where they discussed opportunities to cooperate. It lasted two meals.

Now the two men, in Parris’ words, “despise each other.” Ledford says Parris is a bully and believes he is sowing chaos in an attempt to assert greater control over the region. Parris says Ledford runs Palmdale as a personal fiefdom and will say anything to achieve political objectives.

Their grievances keep piling up. In a 2010 State of the City Address, Parris said he wanted to keep Lancaster a Christian community. Ledford was a member of a county task force on hate crimes that responded by labeling Parris’ comments a hate incident.

That same year, Parris called sheriff’s deputies to a meeting of the Antelope Valley Transit Authority where Ledford was present. Parris said he wanted to seal the meeting as a crime scene after learning that the agency’s director, Randy Floyd, was being investigated for extortion. Afterward, Ledford publicly criticized Parris for overreacting. (Floyd later resigned.)

Parris, a trial attorney, said that by the time he decided in 2012 to help the Antelope Valley Chapter of the NAACP sue Palmdale for racially biased elections, his relationship with Ledford was a lost cause.

“My thinking was, we’re never going to be friends,” he said. “Why shouldn’t I do it?”

Parris deposed Ledford for more than six hours in a frequently confrontational interrogation whose topics ranged from the brand of Ledford’s heart attack medication to the personal finances of Ledford’s wife. The judge ruled against Palmdale, and the city is appealing.

Both mayors describe the squabbling with strikingly similar language.

“Children will be children,” Ledford said. “I don’t think the adult community here sees anything positive in what he’s doing.”

“I’m hoping an adult will get elected to [Palmdale] mayor at some point,” Parris said. “Hope springs eternal.”

As for the Chuckie doll incident?

“I think that any time I want to make a joke,” Parris said, “he is fair game at this point.”

Developer Scott Erlich, who has been involved in several large retail projects in Lancaster and Palmdale, said the drama is hurting both cities.

“It’s frustrating from both a business and a logical perspective,” Erlich said.

Arnold A. Rodio, the principal of Cactus Curtain LLC, said his company’s name is just a private joke. But his take on local politics is somewhat personal. His father was former Lancaster Mayor Arnie Rodio, and he himself has run for mayor twice and lost.

“I’ve got grandkids,” said Rodio, who formed the company to buy a large property on Avenue M. “This fighting means less money for parks, tree-trimming, paving on the streets, and paying for streetlights instead of setting up lighting districts and dumping the cost on the homeowners.”

In 2011, Palmdale florist Chris Spicher and Lancaster social media marketer Jim Greenleaf began an effort to encourage civility between the two cities with an initiative called “AV Nice.”

They hand out wristbands stamped with smiley faces, and their YouTube channel has more than 50 videos that chronicle cherry-picking tours, sports victories, the Antelope Valley Fair and other community events.

“It’s all about having a conversation.” Greenleaf said. “We were tired of living behind the Cactus Curtain.”

One of their first videos featured Palmdale City Manager David Childs, who bought 100 wristbands for his staff.

Greenleaf says they’ve started to gain some traction, but they’re still missing one important supporter: his hometown of Lancaster.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.