Sylmar Jolted by Ghosts of Horror Past

Beate Heuss had nearly conquered her fear when she felt it again.

That’s why it was so terrifying. It was happening again. She and her husband, David, were in bed, like the last time. In a mobile home, just like the last time. It was, in fact, the same mobile home, at the same trailer park.

“This one felt much worse,” she said afterward, calm but able to remember every tremor, then the shaking, then the violence. “It was much harder, a hard jolt. The ’71 one swayed a little.” But this one did not sway. It simply slammed David and Beate Heuss and their community. Again.

Sylmar does not look cursed. It is just half an hour from the heart of Los Angeles, but rural enough for corrals.

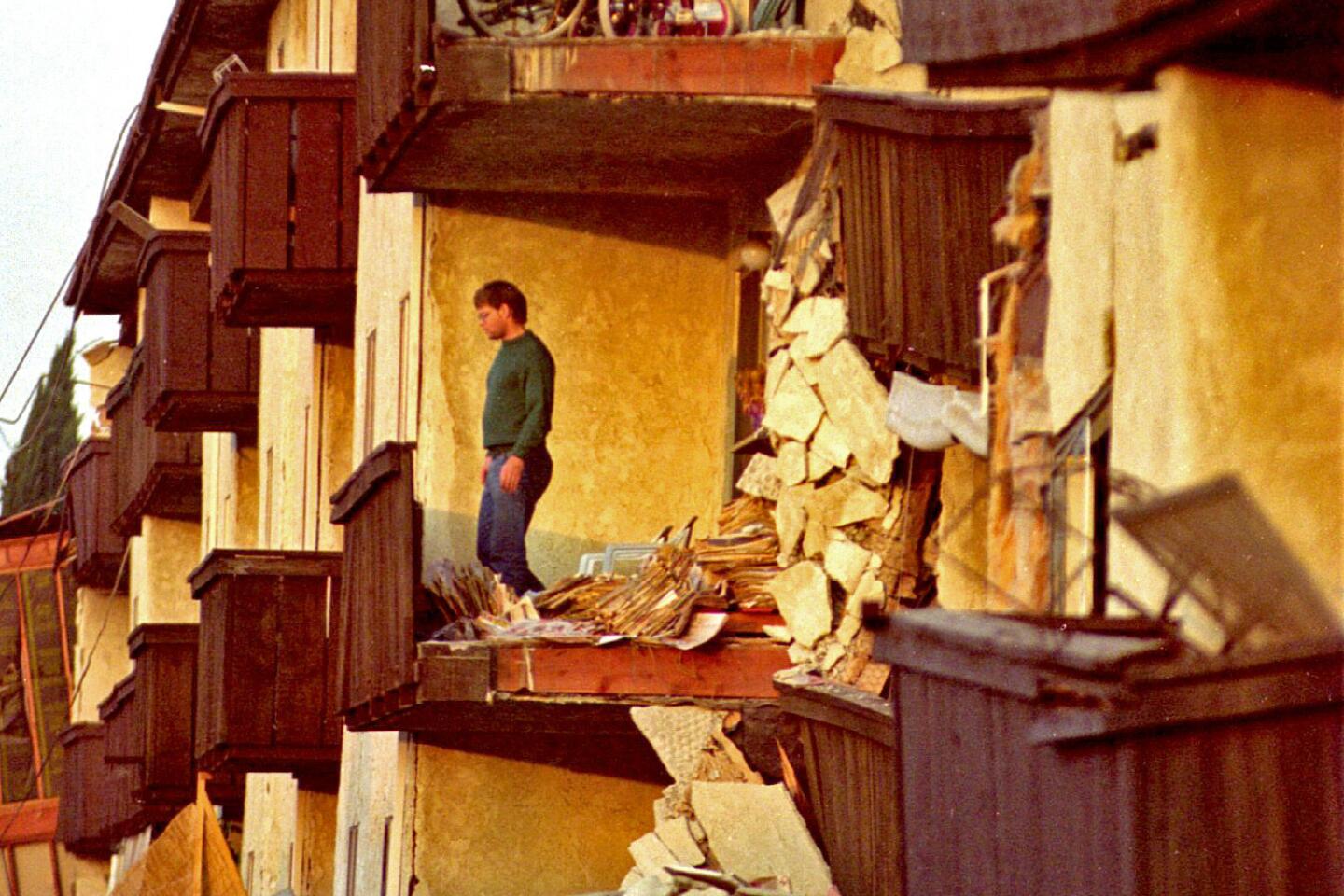

But at 4:31 a.m. Monday, in the quiet darkness, ruin struck with thunder and vengeance--for a second time. It trampled Sylmar and its peace of mind, and when the shaking finally stopped, roads had crumbled, structures had collapsed and homes had been destroyed--for a second time.

Sylmar, where a 6.5 earthquake killed 58 people in 1971, was suffering once more Monday. To some, it seemed like a curse. To others, the curse was like a prayer.

Nobody was killed this time, but scores were injured. More than 50 people were treated at a makeshift, outdoor emergency room at Olive View Medical Center, which was destroyed in 1971 and rebuilt, smaller and better prepared.

Indeed, in some ways, much of the rest of Sylmar was more prepared too. But in other ways, it was simply impossible to get ready.

“I was just getting to the point, personally, where I was getting over being afraid of going under overpasses,” Beate Heuss said. But she was hardly prepared to lose her home.

This time the mobile home, at the Tahitian Mobile Home Park, where the Heusses had lived since the Sylmar earthquake, burned to the ground.

David and Beate Heuss, 54 and 51, lost everything.

They fled with her purse and the clothes on their backs. “Now everything is gone,” she said. That included many of the things they had accumulated during the years that her husband had worked as a quality assurance inspector at Southern California defense plants.

They will leave. Heuss retired not long ago, and he and his wife were planning to move to the Reno area anyway. Beate Heuss was able to smile a bit at the irony. They would go for certain now; there wasn’t much to keep them here.

This time, in fact, the quake was worse--a 6.6. But its epicenter was south of Sylmar, in Northridge. Nonetheless, much of the damage in Sylmar was the same. Freeways were ravaged. Railroad tracks were twisted. Trains were derailed. Fires raged in Sylmar homes.

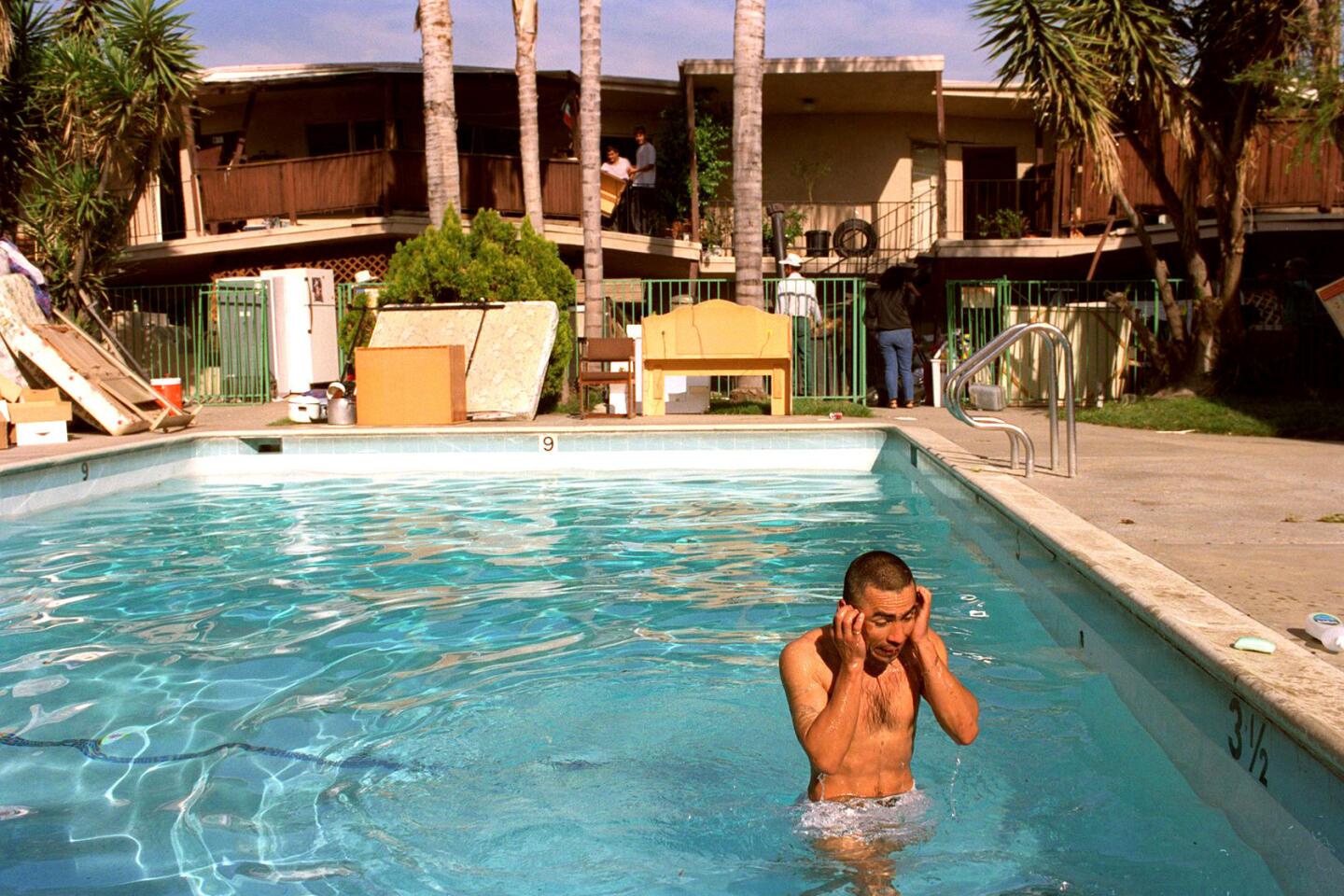

First the homes rose, then fell, and their foundations--little more than jacks under some of the house trailers--punched up through the floors. Furniture flew, and broken gas lines hissed. The gas caught fire, destroying up to 150 homes, by Fire Department estimate, in three Sylmar trailer parks.

Clinton Stone, 30, a Tahitian Park resident, lived in Glendale in 1971. He remembers looking out a window and watching buildings shake. But this time, he said, “it was like the Jolly Green Giant sat down on us.”

This time, clouds of dust rose and obscured the chaparral on the foothills. And this time, there were more people to feel the quake. Sylmar has grown--by a third in the last decade. A census last year counted 59,996 people.

Many of them had come from places where there are no earthquakes--or at least smaller ones.

Mya Dobson, 23, an insurance claims adjuster from Oakland, was staying at a hotel in the San Fernando Valley when the quake hit. Dobson said it felt bigger than the Loma Prieta quake that struck her hometown more than four years ago.

“In Oakland,” she said, “it was like one big hard bang. . . . Today it was long and hard and wouldn’t stop.”

Dobson, a friend and several others spent much of the day at Veterans Memorial Park in Sylmar. In 1971, it was the site of a Veterans Administration Hospital. Two major buildings at the hospital collapsed in that quake, killing 49 patients and employees.

The hospital was never rebuilt.

In its place is a park placed against the foothills that looks out over the Valley. Teresa Mesa, 30, sat in the shade of a tree, figuring it was better to picnic than go home where windows might still be shattered by aftershocks.

Sal Rodas, manager of the Red Cross shelter established at Sylmar High School, estimated that more than 300 people had stopped by for first aid, food or other assistance. He said 150 people or more might stay the night, although dozens chose to sleep on cots under the stars rather than inside the school gymnasium. Lasagna was served, courtesy of the L.A. Unified School District Food Services Division and Pango-Pango Motion Picture Location Catering, which volunteered a truck.

As night fell, scores of people in Sylmar took to their yards. They barbecued dinner. Some gathered belongings about them. Dorothy and Don Miller were in their back yard amid stacks of unbroken china and stemware rescued from their dining room.

They were veterans of the 1971 quake. Dorothy Miller, puffing on cigarette on the patio, said they had no plans to move. “But you never really get used to it,” her husband said from his spot on a blanket on the lawn.

Dorothy Miller, a senior supervisor at the Sierracin Corp., was at work during the 1971 temblor. “We make windshields for airplanes. There was glass flying everywhere. In fact, I thought it was an explosion.”

This time, she and her husband were at home. They had set the alarm for 3 a.m., because Dorothy was headed for work early. It was just as well because when they took a look at their bedroom after the quake, two mirrors, a dresser and a tall set of shelves had toppled onto the bed.

At Olive View Medical Center, two buildings collapsed in 1971, and three people died, including two patients on life-support systems that failed when auxiliary generators did not start. The third was an ambulance driver who was crushed by a falling wall.

Olive View was an 888-bed hospital then. It had only been open a month when the quake hit. Because of extensive damage, the hospital was rebuilt, with attention to strengthening it against any future quake. But it was much smaller. Now it has a capacity of 377 patients.

There were about 300 in the hospital before dawn Monday, said Mario Sewell, an assistant administrator. Half were transferred or discharged, and the hospital does not expect to take any new patients for at least 48 hours.

Sewell said the hospital had water damage, broken tiles and loss of power. A few members of the staff suffered minor injuries, he said, but none of its patients was hurt.

Cherry Uyeda was assistant personnel officer at the hospital in 1971; now she is director of public relations. What would she say to someone who thought Sylmar was a hard-luck place?

“I don’t go along with those who say it’s a hard-luck city. It’s a beautiful city in a beautiful setting. Olive View has always had its facility here, and I’d hate to see us move. . . . We’ve had problems, fires and now two earthquakes.

“But we’ve always come through.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.