In the aftermath of a police shooting, families feel left in the dark with more questions than answers

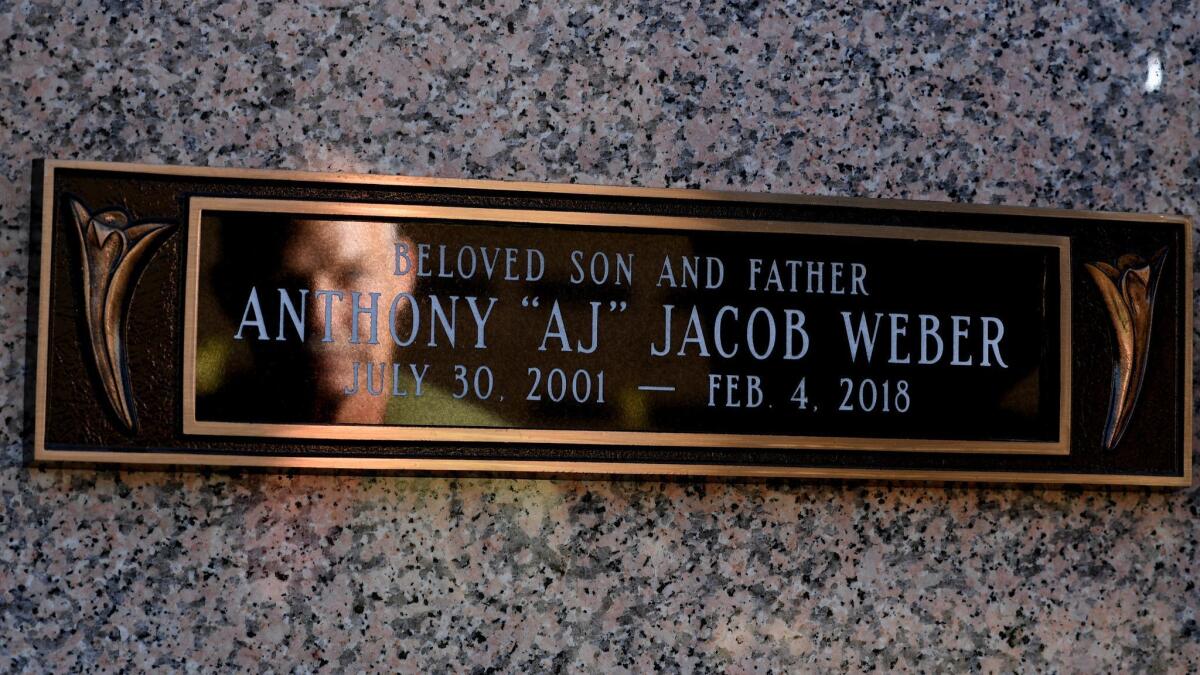

John Weber had a list of questions for authorities after his 16-year-old son was killed by sheriff’s deputies during a February encounter.

What exactly happened in the moments before Anthony Weber was shot in a South L.A. apartment courtyard? Was he wounded in the back as he was running away? Did he lie on the ground struggling for life, or die instantly? Who were the deputies? How long had they been on the job? What were their records?

But after several months, Weber was not able to get many answers. The autopsy has yet to be released, and the Sheriff’s Department has refused to provide Weber or the public the names of the officers involved. After the Weber family filed a civil rights lawsuit, the Sheriff’s Department said in a statement that collecting evidence can be a “painstaking, detailed process,” and that it will “remain silent” as it continues to investigate the shooting.

The case is a window into the frustrations family and friends sometimes experience to get information about police shootings. In California, law enforcement has broad discretion on what details to release during investigations. Peace officer personnel records are also confidential, and only a judge can order their release as part of an ongoing lawsuit or criminal matter. It is also rare for an officer to be prosecuted for an on-duty shooting: The Los Angeles County district attorney’s office hasn’t filed charges against an officer since 2000.

But amid growing focus and protests over police shootings, departments are grappling with how to address public demands for information while preserving the investigation and complying with officer privacy rules. Some of this pressure has come since the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, which has protested police shootings of African Americans.

After 22-year-old Stephon Clark was fatally shot in his grandmother’s Sacramento backyard in March, the local police chief asked the California attorney general to oversee the investigation. The department released hours of body camera footage, and an autopsy was reviewed by four forensic pathologists before its release less than two months after the shooting.

In the wake of several incendiary killings, the Los Angeles Police Department in 2016 created a family liaison unit, which meets with relatives at the scene of shootings or other deaths by police to help guide them through the often-complicated aftermath.

“You’re dealing with human beings at ground zero of the grieving process,” said Sgt. Ruthann Chavez, one of two team members. “Their loss right now is the only thing on their minds, the only thing on their hearts. We just want to make sure that they’re comfortable and they feel safe.”

The Sheriff’s Department has no such unit but said that homicide investigators are a family’s main contact after a police shooting. Families also receive a pamphlet outlining the investigative process. In some cases, like Weber’s, the department said an autopsy remains on hold pending the outcome of ongoing investigations by the Office of the Inspector General and the district attorney’s office.

But the shooting of Anthony Weber prompted the department’s Civilian Oversight Commission to explore better ways of communicating with families.

“We’re trying to figure out ways to help soften that blow, if possible,” said executive director Brian Williams. “There are occasions where you have a family member of someone who has passed away and they just don’t want to see someone in a uniform or badge.”

The shooting of Anthony Weber sparked an angry town hall meeting in which residents demanded answers from authorities about the incident.

According to the department, a person called deputies and said a young man in blue jeans and a black shirt pointed a handgun at a driver near West 107th Street in the Westmont neighborhood. Deputies encountered Anthony, who they said matched the description. Authorities said they saw a handgun tucked in his pants, and when deputies ordered Weber not to move, he took off running to an apartment complex known as a gang hangout.

Anthony turned toward deputies, who fired about 10 rounds, striking Weber several times, the department said. After the shooting, dozens of people flooded the courtyard where Anthony lay dead and deputies called for additional help. Investigators never found a gun and said it could have been picked up by someone in the crowd. The family denies Anthony had a weapon.

“They need to give us more support,” John Weber said recently.

Geoffrey Alpert, a University of South Carolina professor and expert in police procedure, said law enforcement is in a tough position after a police shooting, weighing what information to give out without compromising an investigation.

“You have competing goals and competing interests and someone’s got to balance them,” he said. “You also want to deal with a family that is going through enormous grief. And at this point you don’t know what happened.”

Over the last decade in Los Angeles County, an average of 50 people were killed each year by law enforcement, according to a Times analysis of coroner’s records. National figures are elusive: Agencies aren’t required to report officer-involved deaths. But the LAPD and the Sheriff’s Department are believed to have among the highest numbers of fatal shootings in the nation.

Janet Williams, whose son, Dennis “Todd” Rogers, was killed by Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies last year, said she didn’t learn of his death until his ex-wife received a message from the coroner’s office, a week later.

On March 7, 2017, Rogers had been asked to leave a 24 Hour Fitness in Baldwin Hills. Deputies responded and Rogers, who had a history of mental illness, agreed to leave the area. Hours later, the manager of the gym called authorities again, and said that Rogers was still in the area and had been threatening him.

Deputies returned and Rogers had become aggressive, officials said. At one point he pulled out electric hair clippers and officers fired.

More than a year later, Williams said she still doesn’t really know what happened. An autopsy report that was on hold for 15 months was released this month after The Times asked about the case.

“You got everybody trying to protect the police,” Williams said. “But nobody is concerned about the family.”

The department declined a request to interview the head of the sheriff’s homicide bureau but said in a written statement that it makes every effort to inform the family of a person killed by deputies so they don’t find out through a third party and sends them condolence letters.

“We will strive to keep them informed of the progress of the investigation, while understanding the legal limitations and attempts to maintain the integrity of the case, pending a determination of criminal culpability,” the statement said.

At a recent sheriff’s commission meeting, a district attorney’s representative outlined services it provides to crime victims, including financial assistance for the funeral and help finding counseling. Some of those services are funded by the state’s victim compensation program, which receives funds partially from through restitution paid by inmates and individuals convicted of crimes.

If the death was the result of a crime, such as a drive-by shooting, a family could be eligible for services. But investigations into police shootings can take months or years, and usually, officers are not held criminally liable. A person who died while committing a crime or on probation would not be eligible for services, said Michele Daniels, director of the district attorney’s program.

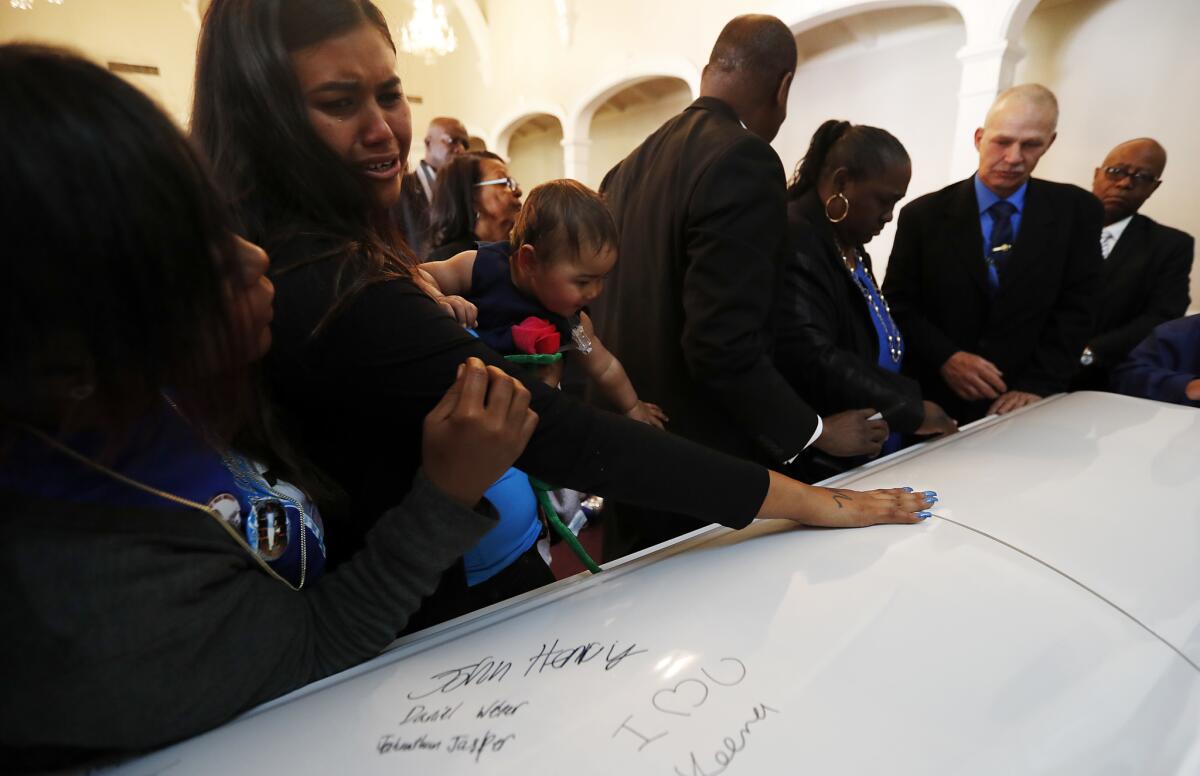

The Weber family raised money online to pay for Anthony’s funeral. But the trauma of losing a sibling has weighed on the younger Weber brothers, including a 9-year-old who has been acting up in school.

Dale Galipo, a California attorney who specializes in police misconduct cases, said the compensation program should include such families. Even a simple “I’m sorry” from law enforcement could go a long way, instead, “they force these people to get lawyers,” said Galipo, who is representing the Webers in the civil lawsuit.

Beverly Rogers had a different experience after her son was killed by LAPD officers in downtown Los Angeles in January 2017. Michael Rogers, 32, was shot after police said he tried to carjack a city worker with a knife, threatened people in a nearby exercise studio, then ran toward approaching officers.

That day, Michael Rogers’ girlfriend discovered 32-year-old Lisa Ramirez, a custodian at the complex, dead in the apartment she shared with Rogers. Police think Rogers was responsible for Ramirez’s death.

His mother said that members of the family liaison unit answered questions after the shooting and helped connect her with the coroner’s office.

As the date approached for her son’s case to be evaluated by the Police Commission, the unit explained what would happen at the meeting.

During a break, Chief Charlie Beck spoke with Beverly Rogers and her husband.

“I just felt like he was listening to what we had to say,” Rogers said.

Former Times staff writer Kate Mather contributed to this story

For more crime news, follow @nicolesantacruz on Twitter.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.