L.A. files few charges in Ferguson police shooting protests despite mass arrests

When protesters flooded streets across the country last fall, furious over the police killing of an 18-year-old black man in Missouri, the demonstrations in Los Angeles stood out among the rest.

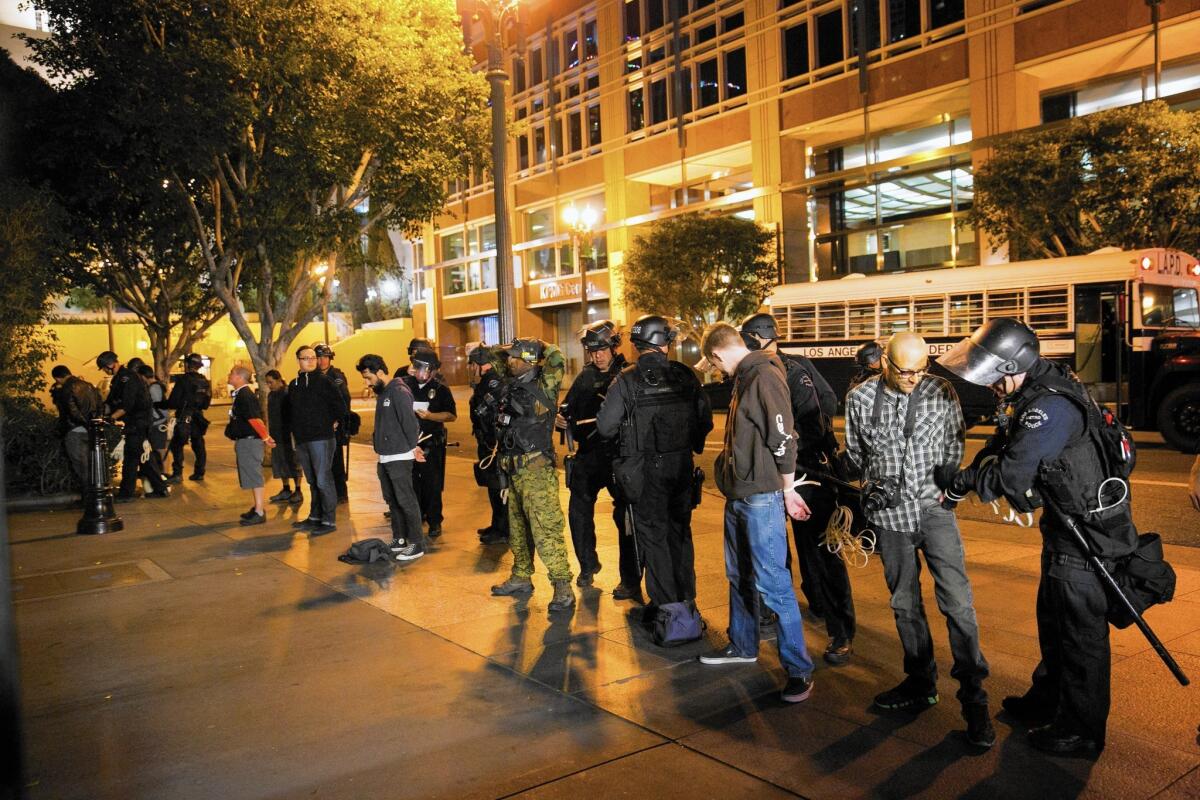

There was no widespread violence, no burning stores or looting, but L.A. made national headlines for another reason: LAPD officers swept up hundreds of protesters in mass arrests. The numbers surpassed those in other cities such as Oakland, St. Louis and Ferguson, Mo., that experienced rioting and other violence.

Eight months later, Los Angeles city prosecutors told The Times they had rejected filing criminal charges against the majority of the people detained by the LAPD during those demonstrations. The city attorney’s office has filed charges against only 27 of the 323 protesters arrested — fewer than 9% — and has formally rejected charges against 181.

Most of the remaining cases were referred to informal hearings, where officials “make sure that everyone understands the law and consequences if this happens again,” a spokesman for the city attorney’s office said.

Los Angeles Police Department officials said they stood by the arrests, despite the small number of charges filed. They noted police have a lower legal threshold — probable cause — for making an arrest than prosecutors do for proving a case.

Capt. Jeff Bert, who oversaw the on-the-ground response to the demonstrations, said the LAPD’s primary objective was to allow protesters to exercise their 1st Amendment rights. But he said that when concerns arose about public safety — such as when protesters ran onto the freeway or blocked traffic — the department needed to take action.

“There comes a point where enough is enough, when we are balancing the needs of the rest of Los Angelenos with the needs of a very small, relatively speaking, group of protesters who are no longer engaging in lawful activity,” he said. “Our actions, while not popular, were actions designed to protect and keep the city safe.”

Larry Rosenthal, a former deputy city attorney in Chicago and law professor at Chapman University, said that it’s not uncommon to see only a few charges filed after a large demonstration resulting in mass arrests. In such chaotic situations, he said, police officers don’t always have the time to adequately record the alleged offenses.

“There’s great tension between getting control of the scene and being able to document what’s been done in a way that will hold up in court,” Rosenthal said.

But critics of the LAPD’s tactics said the city attorney’s decision bolstered their complaints that police went too far by arresting so many people.

“They overreacted,” said Carol Sobel, a longtime civil rights attorney who has alleged in legal papers filed with the city that police acted improperly. “They could have handled it differently.”

Peter Bibring, a senior staff attorney for the Southern California chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, said Los Angeles police should be better trained at this point, given the department’s checkered past with large demonstrations. The LAPD was blasted for its heavy-handed response to the 2007 May Day rally in MacArthur Park, where officers swung batons and fired rubber bullets on a predominantly peaceful crowd, injuring nearly 250 people. The melee prompted lawsuits and LAPD reforms.

“To me, this suggests there are breakdowns,” Bibring said of the LAPD’s handling of the November protests. “That officers aren’t getting the message and are arresting people who aren’t actually the ones violating the law.”

Police alleged that many of those arrested refused to leave areas after being warned by police. The charges filed included obstructing thoroughfares, refusing to comply with lawful police orders, and assault or battery on officers, according to the city attorney’s office.

City attorney spokesman Rob Wilcox said via email that his office “carefully reviewed each case and based on the available evidence made a decision whether to file.” Generally, he said, prosecutors may reject charges in mass-arrest scenarios because they can’t prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a specific person committed a specific crime.

Wilcox said prosecutors “worked together closely” with the LAPD “to address the challenging and unique circumstances presented by the Ferguson protests.”

“It is one thing to peacefully protest on a sidewalk outside City Hall and quite another to assault a police officer or endanger lives on the freeway … which are totally unacceptable and will be prosecuted,” he wrote.

Like other major police agencies, the LAPD braced last November for the local reaction to a decision made by a grand jury not to indict the white police officer who fatally shot Michael Brown in Ferguson. Although the L.A. protests generally remained peaceful, tensions sometimes flared.

Groups of demonstrators sat down in the lanes of the 110 Freeway downtown, holding their hands in the air. One protester was arrested on suspicion of throwing a frozen water bottle that struck an officer in the head. Other people were photographed climbing on top of police cars.

A common complaint among many protesters was that they didn’t hear a so-called “dispersal order” from the LAPD telling them to leave the area.

Bert said he personally delivered dispersal orders, but acknowledged that giving the commands posed challenges, particularly during the first night of demonstrations. Bert said he would have liked to have had officers on the other side of the crowd confirm to him that they could hear the order.

Two nights later, Bert said, he had those officers in place and they told him they could hear his dispersal order. But when an attorney who was observing the protests told Bert he didn’t, the captain said, the command was given again.

Charmaine Chua was among the dozens of people arrested on suspicion of failing to disperse the day before Thanksgiving near 7th and Figueroa streets. She said she never heard the LAPD give an order to leave before officers penned her and other demonstrators into an area where they were detained.

After she was released from a Van Nuys jail, Chua said, she connected with other protesters and met with attorneys to discuss their cases. They believed the arrests were a ploy by police to end the days-long demonstrations, she said.

“It felt like a scare tactic,” Chua said.

Chua’s case ended with a five-minute meeting at the city attorney’s office, she said, where she was told she was arrested because the demonstration was becoming a riot. The city attorney’s office warned her to stay out of trouble, she said.

Cori Redstone, another protester arrested that night on allegations of failing to disperse, said she was given paperwork ordering her to court on what turned out to be a federal holiday.

“I don’t know if I’m charged or not. I have no idea what is happening with my case,” she said recently.

Redstone, who recently completed a graduate degree at CalArts, says she is applying for teaching jobs. She worries the arrest will keep her from getting hired.

“I guess it’s a consequence I’ll have to live with now,” she said.

Wilcox said this week that his office had decided not to file charges against Redstone.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.