The history of measles: A scourge for centuries

Measles has been a scourge for centuries, afflicting millions of people. It has been blamed, in part, for decimating native populations of the Americas as Europeans explored the New World. In modern times, before a vaccine was developed, nearly every American contracted the virus, with its telltale skin blotches and fever. Measles was declared eradicated in the U.S. in 2000, but has staged a comeback as the inoculation rate has dropped. Here’s a history:

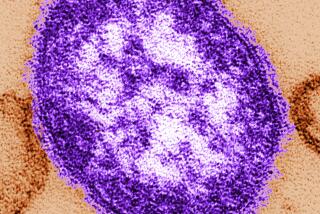

3rd to 10th century: Early physicians in Asia and North Africa identified and diagnosed measles, which was similar to smallpox, another highly contagious disease that triggered rashes and sores. Modern scientists would later suggest that measles evolved after the rise of early civilization in the Middle East and may have come from animals; the virus was highly similar to rinderpest, which infected cattle.

In 340, Chinese alchemist Ko Hung described the difference between smallpox and measles; a Christian priest, Ahrun, did the same in Egypt about 300 years later. In 910, the Persian physician Rhazes published the most widely celebrated early diagnoses of the two diseases.

1492: In a pattern that would be repeated across the world for centuries, Christopher Columbus and his fellow European explorers arrived in the Americas, bringing a raft of deadly diseases — including measles — with them.

Native Americans had no natural immunity to many of these diseases. Measles, smallpox, whooping cough, chicken pox, bubonic plague, typhus and malaria — already dangerous and often deadly in Europe — became even more efficient killers in the New World. By some estimates, the Native American population plunged by as much as 95% over the next 150 years due to disease.

1824-48: As was the case with many diseases, measles’ risk to Pacific Islanders was particularly dangerous in the 19th century as traders and travelers crisscrossed the globe. In 1824, Hawaii’s King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamamalu traveled to London to meet King George IV, but instead swiftly contracted measles. Both died within a month. The virus, along with several other diseases, struck Hawaii in 1848, killing up to a third of the native population.

1846: Danish physician Peter Ludwig Panum traveled to the Faroe Islands between Iceland and Norway to study a measles outbreak that had sickened more than 75% of the islands’ 7,782 residents — killing at least 102. Measles had not appeared on the isolated islands in decades, and Panum discovered that “not one” of the elderly residents who had been infected in 1781 “was attacked a second time.” Such immunity would later become key to defeating the virus. Panum observed measles’ contagiousness as it leaped from village to village.

1875: The HMS Dido brought measles to Fiji, killing 20,000 people — up to a third of the island’s natives. Measles outbreaks would continue to hopscotch Pacific islands for much of the next century.

1912: The United States required physicians to start reporting measles cases, which gave scientists a precise grasp of the disease’s widespread impact inside the country. Almost all Americans caught measles sometime in their life – mostly when young – and the outcome could be deadly. A study in the U.S. from 1912 to 1916 found 26 deaths for every 1,000 measles cases.

1954: Thomas C. Peebles, a World War II bomber pilot turned doctor, isolated the measles virus in an infected 11-year-old boy named David Edmonston. Peebles’ work paved the way for a vaccine.

1963: The first measles vaccines were licensed in the U.S.

Measles’ lethality had dropped by the 1960s, thanks to improved treatment and nutrition, with less than one death reported for every 1,000 cases. But before the vaccines, millions of American children were infected every year, and many developed serious side effects: An annual average of 48,000 measles patients required hospitalization, with 400 to 500 deaths per year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The most serious side effects included pneumonia and encephalitis – swelling of the brain. Hearing loss from measles-related ear infections was also common.

Measles vaccines slashed those infection rates. Over several decades, the vaccines were were bundled with vaccines for mumps and rubella into a booster shot parents now know as the MMR. State legislatures began mandating vaccination for school students in the 1960s and 1970s, and eventually every state and the District of Columbia adopted such laws, with some exemptions for medical, philosophical or religious reasons.

1989-91: A measles outbreak in the U.S. brought 55,000 cases, 11,000 hospitalizations and 123 deaths. The virus infected some vaccinated patients in the U.S., leading experts to begin recommending a second dose of MMR.

For the next decade, measles infection rates grew so low that, by 2000, measles was declared effectively eliminated in the U.S. But the virus remained prevalent around the world.

1998: A report in the British journal Lancet claimed a possible link between the measles vaccine and autism. Although the report was later debunked as fraudulent, its publication and a 1982 documentary called “DPT: Vaccine Roulette” aroused parents’ fears that vaccines might harm their children and spurred requests for vaccination exemptions.

The Lancet retracted that paper in 2010, and its author, Dr. Andrew Wakefield, lost his medical license. An investigation found that Wakefield had manipulated his data and altered patients’ medical histories to make his assertions more convincing.

“The MMR scare was based not on bad science but on a deliberate fraud,” Dr. Fiona Godlee, editor in chief of BMJ, formerly known as the British Medical Journal, wrote in 2011. Such “clear evidence of falsification of data should now close the door on this damaging vaccine scare.”

That did not happen, however. If anything, vaccination refusal rates continued to grow in some American communities. Scientists say at least 92% of a population must be vaccinated for so-called herd immunity to protect virtually everyone. As the vaccination percentage drops, the risk of outbreak rises.

2014: The worst American measles outbreak in two decades erupted, with more than 600 cases reported -- more than triple the 2013 total. One outbreak came in unvaccinated Amish communities in Ohio, where a missionary had traveled to the outbreak-ridden Philippines and returned home with the virus. Another outbreak came at Disneyland in December.

The Disneyland outbreak caused at least 52 of the 79 measles cases reported in California near the end of January, state officials said. By Jan. 31, a total of 102 measles cases had been reported in 14 states. At least two cases were reported in Mexico.

The Disneyland outbreak continues to draw scrutiny to anti-vaccination sentiments in California, where the rate of personal-belief vaccination exemptions at kindergartens with at least 10 students doubled to 3.1% in 2013 from 1.5% in 2007. That increase was driven largely by parents in wealthier school districts, many of which have fewer than 92% of kindergarteners immunized.

In the Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District, for instance, nearly 15% of students last year were not vaccinated; that number has now dropped to 11.5%, school officials say.

Measles continues to survive around the globe, causing 145,700 deaths in 2013, the World Health Organization says. Although the number of deaths have dropped by 75% between 2000 and 2013 because of vaccine use outside the U.S., the WHO says the virus remains “one of the leading causes of death among young children even though a safe and cost-effective vaccine is available.”

Rosanna Xia and Rong-Gong Lin II contributed to this report. Sources include: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; “Smallpox and its Eradication,” the World Health Organization; “The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas,” by Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian. “Observations Made During The Epidemic Of Measles On The Faroe Islands In The Year 1846,” by Peter Ludwig Panum. “Measles Elimination in the United States,” the Journal of Infectious Diseases. “Diseased Goods: Global Exchanges in the Eastern Pacific Basin, 1770-1850,” by David Igler.

Follow @MattDPearce for national news

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.