For Dean Potter, BASE jumping was spirituality, not sport

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK, Calif. — They experienced a rarefied state — a gap between life and death as narrow as the notch they were attempting to clear at dusk Saturday.

Their mountaintop leaps in high-tech wingsuits were often described as “extreme sport.”

But Dean Potter believed that missed the point of his breathtaking flights — what he called the “dangerous arts.” On his website he wrote that he was misunderstood when his “spirituality is considered sport.”

The ever-present risk of death, he said, allowed him to “play in the void.”

Related: Fellow climbers try to come to terms with deaths of Dean Potter, Graham Hunt

As word spread of Potter’s death at the age of 43 — and that of his protege, Graham Hunt, 29, — fellow climbers and BASE jumpers gathered Monday at Yosemite to reflect on their lives, deaths and meticulous dedication to their dangerous, sometimes illegal, pursuit.

“Both loved Yosemite very much and did it not because it was illegal but in spite of it,” said Lori Butz, 42, of San Francisco, a wingsuit flier who knew Potter and Hunt. “It’s getting to do the most awesome thing in the world in the most awesome place in the world.… The pursuit of human flight is universal. Doesn’t everybody want to fly?”

BASE jumping involves leaping off a fixed structure or cliff with only a parachute, and sometimes a wingsuit intricately engineered to soar like a flying squirrel.

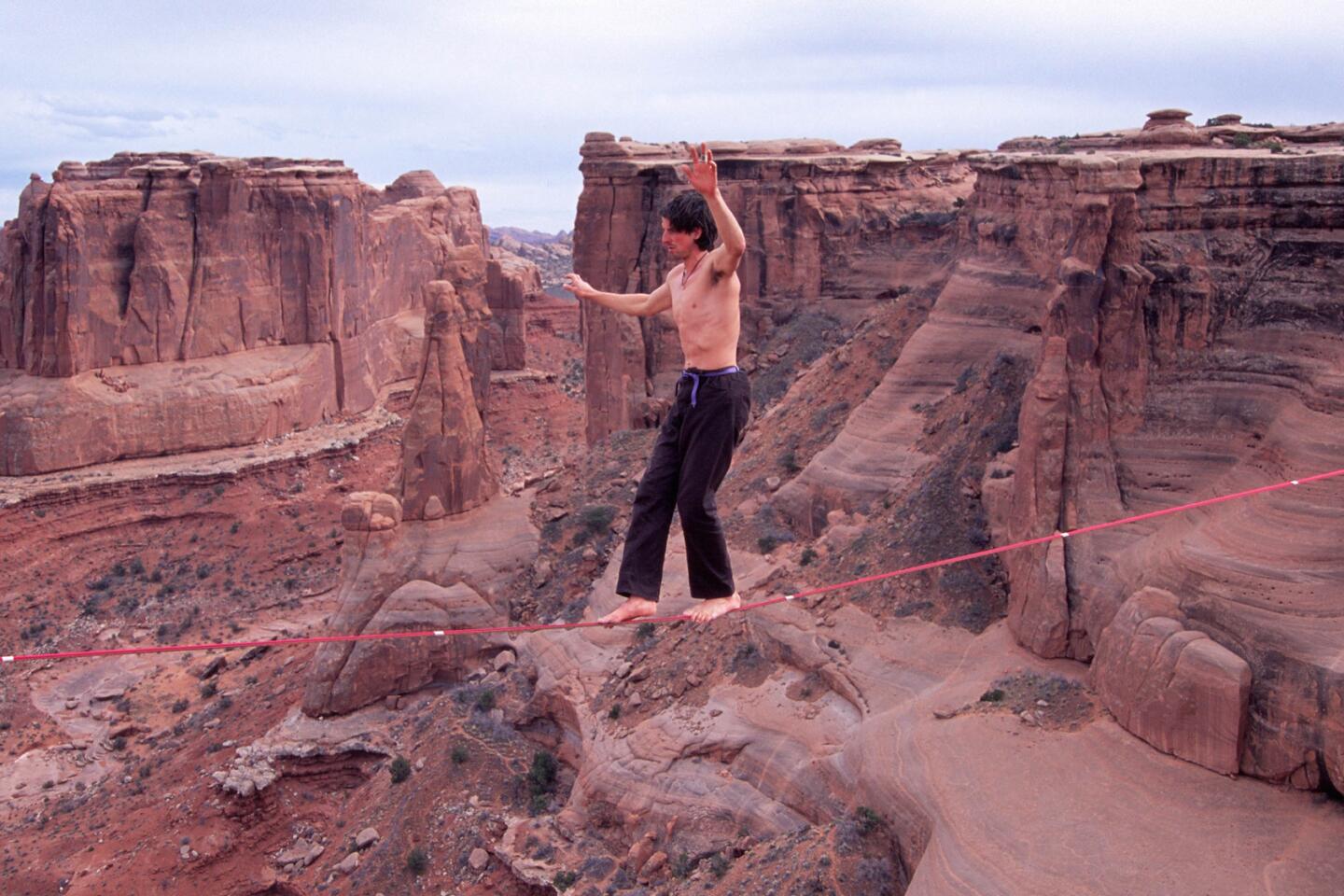

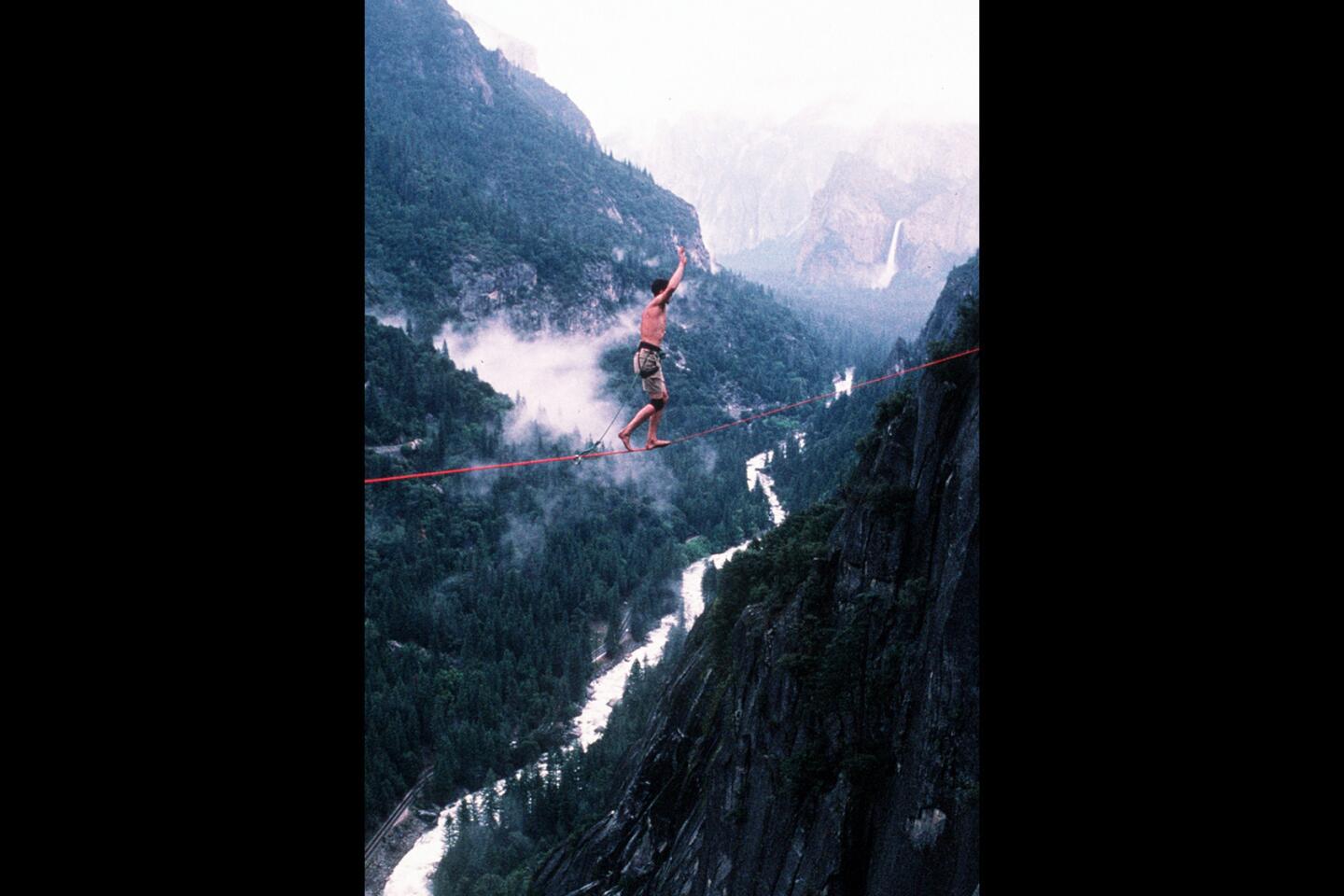

Potter, celebrated as one of the world’s best aerialists, had set records not only for wingsuiting, but also for free climbing — ascents where ropes are used only to arrest falls — and BASElining — crossing chasms on an elevated line with a backup parachute.

(BASE stands for buildings, antennae, spans and earth — meaning cliffs and mountaintops.)

BASE jumping in national parks is banned under federal law. Those who are caught and cited in Yosemite face fines up to $5,000. Some have been forced to relinquish their gear, said park spokesman Scott Gediman, who estimated that three dozen people make the jumps yearly.

Friends said Potter and Hunt, who lived near the park, pursued their passion methodically. Potter had been studying avian aerodynamics and aerospace technology in Canada with hopes “of safely flying and landing the unaided human body,” according to the biography on his website.

Potter’s affinity for climbing was noted as early as age 5, when he attempted to scale a stone wall that surrounded his family’s temporary home in Jordan, where his father, a U.S. Army colonel, had been assigned. He fell and landed on his head, his mother, Patricia Dellert, told The Times in 1998.

By his mid-20s, Potter, a college dropout, had become known as one of Yosemite’s top climbers.

Hunt was part of a younger generation of climbers inspired by Potter to branch into BASE jumping. His father, Cliff Hunt, said Monday that after growing up in Shingle Springs, Calif., his son worked on a hotshot fire crew before making his way to El Portal, near Yosemite.

He befriended Potter, a neighbor, as well as another renowned jumper, Sean Leary, traveling with Potter to the Swiss Alps a few years ago to hone his skills.

“Even though from the outside it might seem like he was super extreme, his inner psyche was very much in the middle,” said Shawn Reeder, 38, of Nevada City, who had known Hunt for a decade.

He called Hunt “very calculated, very methodical” about jumping only in ideal conditions, adding, “He was chill and mellow, but when he’d go out there he’d give it his all.”

Hunt had described wingsuiting to Reeder as a kind of “alternate freedom.”

But death came. As Potter often contemplated in poetic journal entries that it could. As it had last year to Leary. And to dozens of others before that.

Tom Evans, 71, a climbing photographer from Crestline, knew Potter for two decades. BASE jumpers venture out at dawn or dusk when rangers are changing shifts, he explained at the park’s Camp 4, a longstanding gathering spot for climbers. They jump in quick succession to avoid being caught.

“It’s a game of cat and mouse,” he said, “and the jumpers usually win.”

On Saturday evening, Potter and Hunt hiked to Taft Point with a spotter, who photographed them jumping about 7:30 p.m. — 25 minutes before sunset — said Yosemite chief of staff Michael Gauthier. They were attempting to clear a “notch” on a steep and rocky ridgeline that Gauthier described as “spiny like a stegosaurus.”

Gauthier estimated that Potter had made the jump up to 20 times.

But the jumping-off point, known as the “exit,” is highly technical, said Dean Fidelman, 59, of Santa Cruz, who was among those gathered in the valley.

“It was a place where you had to be an expert,” he said, noting that horizontal speed in a wingsuit reaches 120 mph. “It was two people in a tight place. There was no margin” for error.

The spotter, whose identity was not released, told investigators she heard what she thought sounded like two parachutes opening, or impact. She called out to the men, and tried to contact them as planned, via text. She got no answer.

Gauthier said “photos show that they didn’t collide.” Their wingsuit-clad bodies were found early Sunday on a rock outcropping below the 7,500-foot point. Their parachutes had not deployed.

“Those guys were like the gurus, definitely the best of the best,” said Sean Jones, 45, who was one of Hunt’s early climbing mentors. “That was the one comforting thing for me, that at least Graham was in there learning from the best, and that had Graham becoming the best.”

Potter’s devotion to jumping had placed him at the center of controversy over the years, and he lost sponsorships by Patagonia and Clif Bar. But even people running the park where he consistently flouted federal law were struck by what they called his uncompromising ideals and gentle demeanor.

“It was clear that Dean followed his convictions and heart, and that he did so with complete commitment even when it came at personal and professional cost,” said Gauthier, the Yosemite chief of staff, who described Potter as “sweet and caring [and] incredibly kind.”

Writing in October of time spent on the north face of the Eiger in the Swiss Alps with his longtime girlfriend, Jen Rapp, and their Australian cattle dog Whisper — who often flew, strapped to Potter’s back — Potter contemplated death and marveled at his good fortune.

“Wingsuit BASE-jumping feels safe to me but 25 wingsuit-fliers have lost their lives, this year alone,” he wrote. “There must be some flaw in our system, a lethal secret beyond my comprehension.”

Three years earlier, he had set a record on the mountain — soaring in his wingsuit for 3 minutes and 2 seconds and making a perfect landing.

“I guess all the night flying I do to avoid being arrested must teach me to feel the air more acutely than daytime flying,” he pondered, saying that he had come to think of himself as “more bird than human.”

Potter added: “It’s still not right that I’m a criminal in my home town and that I can’t legally fully spread my wings in ‘The Land of the Free.’ ”

Friends struggled with the new reality.

“This is not a suicide mission,” Evans said. “Those guys, they think they have it down to a science and most of the time it works out. But when the cream of the crop gets killed, what does it say to the average person?”

Barboza reported from Yosemite, Mejia from Los Angeles and Romney from San Francisco.

Times staff writers Hailey Branson-Potts, Christine Mai-Duc and Javier Panzar contributed to this report.

Twitter: @brittny_mejia

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.