How do coyotes thrive in urban Southern California? The answer is not for the weak-stomached

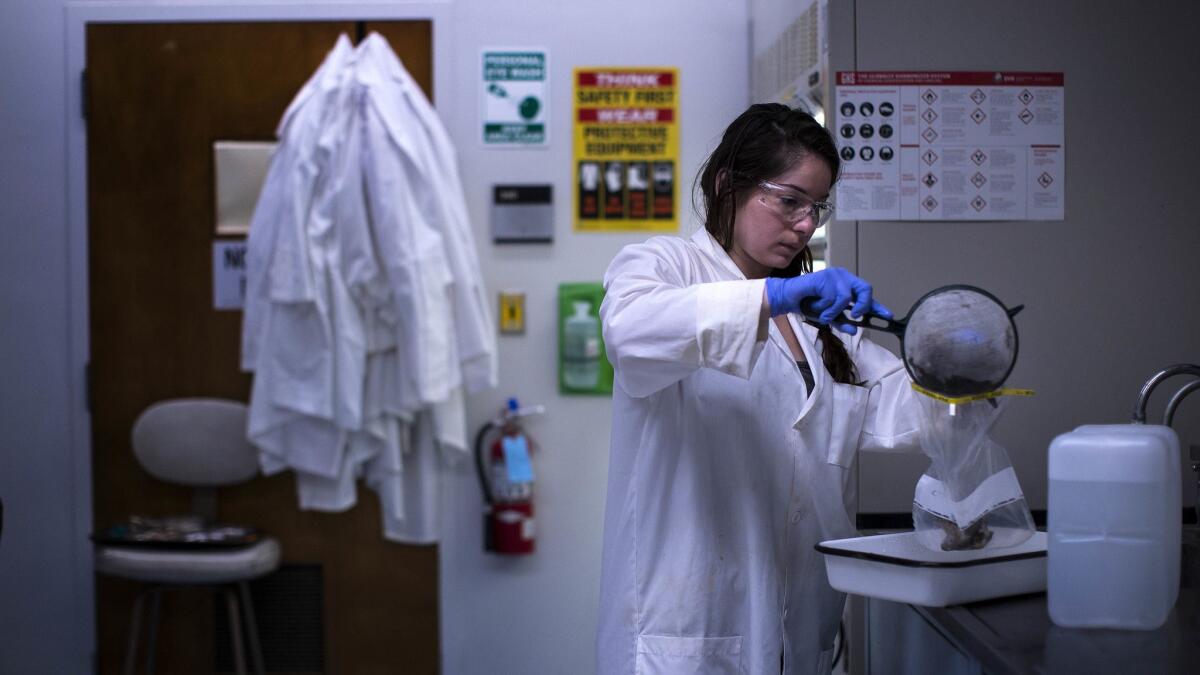

Danielle Martinez donned a lab coat, pulled on a pair of latex gloves and adjusted her safety goggles in preparation for one of biology’s little surprises.

“They’re like Christmas packages,” she said of the cantaloupe-sized coyote stomachs before her. “You never know what you’re going to find inside.”

Martinez is part of a team of researchers that for more than a year has been cataloging the astonishingly diverse contents stewing in the bellies of local urban coyotes.

Organs from coyotes that perished across Los Angeles and Orange counties under myriad circumstances are offering fresh glimpses of a biological mystery: Exactly what fits into the diet of the intelligent, socially organized and highly adaptive scavengers in urban settings?

What percentage of the daily smorgasbord is composed of rodents and garbage compared with, say, household pets?

The answer wouldn’t just interest concerned cat owners, but could also help shape effective strategies for managing the species in urban areas.

This scientific study is a coyote postmortem on an unprecedented scale — it has so far documented the contents of 104 stomachs and intends to examine 300 by the end of the year. The team, led by Niamh Quinn, UC Cooperative Extension’s human-wildlife interactions advisor, is already generating a wealth of data to better understand how these omnivorous canids sample everything from pocket gophers to hiking boots while managing to survive in a land of 20 million people.

Shoes with rubber soles may seem unsavory, but preliminary results show that urban coyotes gulp them down, along with western cottontail rabbits, birds, avocados, oranges, peaches, candy wrappers, fast-food cartons and an occasional cat.

“Cats seem to make up only about 8% of a local urban coyote’s diet,” said Martinez, 27, a graduate student at Cal State Fullerton.

Another surprise: Remarkably few of the coyotes had eaten roof rats, a ubiquitous rodent that can weigh up to a pound. The researchers theorize that may be because roof rats are fast, superb climbers.

Determining whether a coyote had feasted on dogs — Chihuahuas, for example — is beyond the scope of the study, researchers said. That’s because it would be extremely difficult to differentiate the DNA of the predator from that of another member of the canid family.

The defining characteristic of the decomposed grayish-brown gunk in a coyote tummy, however, is its stench, which lab visitors have described as “shocking,” “disgusting” and “fetid.”

Quinn, who says her lab work keeps her “elbow deep in coyote carcasses,” put it this way: “It’s a sickly sweet smell — like the worst candy you ever had in your life. No joke. But Danielle is a trouper, and I’m used to it.”

Until now, much of the research on what coyotes eat had focused on analyses of scat, which, Quinn says, “is highly inaccurate. Our study will be more precise — down to the molecular level.”

Scat, Quinn said, is less reliable because of the quantity of easily misidentified food sources.

“This much is clear: coyotes aren’t struggling in our urban environments,” she said. “They are almost everywhere, continually learning to adapt alongside us.”

Across Southern California and much of the United States, debate is growing over the most humane and cost-effective methods of executing the wily predators, as is a vigorous push to find ways to live alongside them.

Several cities have adopted coexistence plans with help from wildlife advocacy groups including the Humane Society of the United States and Project Coyote that encourage enforcement of laws prohibiting the feeding of wildlife and the development of a system for determining the proper responses to encounters with coyotes. They range from hazing techniques — shouting, loud whistles and bright lights, for example — to elimination of a coyote involved in documented attacks on humans.

But hazing has limits, some say, when it comes to big-city coyotes.

“We’re making the case that Southern California’s coyotes, by adapting to life in a metropolis, behave differently than those found elsewhere,” Cal State Fullerton biology professor Paul Stapp said. “And it may be that we’re seeing an uptick in coyote bites because people are getting used to seeing these animals hanging around parks and neighborhoods.”

Professional trappers are still trying to catch a coyote that bit a 5-year-old boy and then aggressively approached a student at the Cal State L.A. campus about five miles east of downtown Los Angeles on March 14.

Images of coyotes prowling streets posted on community message boards and the neighborhood-focused social media platform Nextdoor have aroused outrage and fear.

Then there is Coyote Cacher, a UC Cooperative Extension web application developed by Quinn to receive reports of coyote sightings throughout California and let users see when and where they occurred.

Judging from its terse postings, Los Angeles and Orange counties are among the highest coyote conflict zones in the state.

“Was howling at an ambulance going down PCH toward Hoag Hospital in Newport Beach,” a report posted this month said.

“Killed and ate my cat,” said another from the same area.

Thirty-nine people have been bitten by coyotes in Los Angeles County over the last five years, most of them in communities east of downtown, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Twelve people were bitten in the Elysian Park area alone in 2015, and most of those attacks were unprovoked, the department said. Victims included a jogger, a child who had been playing with friends and two people who were sitting on the ground and looking up at the stars.

“The motivation behind all these attacks is unclear,” Quinn said. “It may be that we are living with coyotes, or they are living with us. Right now, we’re not sure.”

The answers may be lying under the researchers’ noses in the lab at Cal State Fullerton.

Following strict laboratory protocol, Martinez used a fine-net sieve to rinse the contents of the stomach from a 30-pound female coyote, euthanized in Newport Beach in June 2016, with distilled water, followed by 95% ethanol alcohol.

Then she placed the material in a white tray under a dome designed to eliminate offensive smells. Using forceps, she picked through the mound, plucking out decomposed evidence of the animal’s life and times.

“We’ve got a small snake,” she said, “a paw, perhaps from a squirrel, and seeds. We also have the tail of a small mammal, and a piece of blue plastic. Hmm.”

Martinez examined samples of hair under a powerful microscope. “Might be from a mule deer,” she said.

Later, using DNA sequencing techniques, the team will make precise identifications of the urban coyote’s food sources, helping determine what really fuels a species that has proved to be one of nature’s ultimate survivors.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.