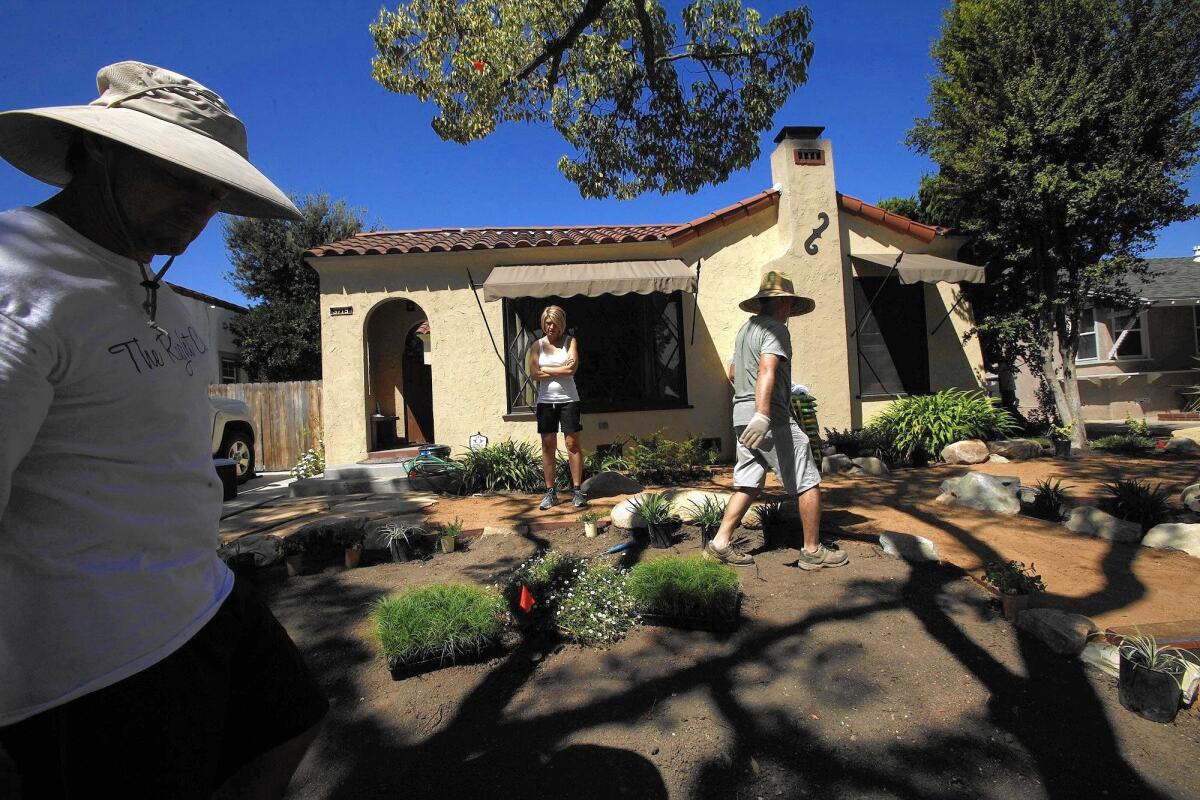

Keeping up with the Joneses’ drought-friendly yard boosted MWD’s tab for rebates

When it came down to it, the number crunchers at the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California knew they saved a lot more water for every dollar spent subsidizing low-flush toilets than drought-friendly lawns.

But there was one thing the MWD planners didn’t bank on when they threw an unprecedented $340 million into persuading residents to tear out their lawns: The value of one-upping your neighbor.

They said it contributed to a rush of rebate sign-ups that, in a matter of weeks, exhausted all the turf removal funds for the rest of the year — and provided an unexpected lesson in social engineering.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

A drought-friendly lawn became a badge of honor, said MWD General Manager Jeffrey Kightlinger, adding, “The toilet is somewhere buried in your house. No one knows if you did the right thing or not.… People want that ‘Yeah, I did the right thing for the drought, and I want people to see it.’”

As the drought got worse and pressures mounted to save more water, MWD gave turf removal a bigger push, even though the numbers said don’t do it. For every $160 the agency spends handing out rebates on drought-friendly appliances, it saves about one acre-foot of water a year. To save the same amount of water via turf-removal rebates? About $1,400.

That’s more expensive than the water itself, officials said. But if it meant more people were actually going to get rid of their lawns, which suck up about 50% of a household’s water, then maybe it was worth it for the future savings.

“We were willing to throw a bunch of money, even if it’s not maybe the most cost-effective tool. I think in the long run, changing that mindset is going to pay off,” Kightlinger said. “If it was just saving water, we’d have preferred to put everything, every dollar into devices.”

With tens of thousands of homeowners signing up to redo their lawns, the rebates this year could help save about 26 billion gallons of water a year — enough to serve 160,000 households annually. For a typical 1,500-square-foot front yard, removing the turf would save up to 66,000 gallons of water a year, officials said.

SIGN UP for the free Water and Power newsletter >>

The turf-removal rebate program has been around for about a decade, but had typically generated little interest. Until a few years ago, MWD had set aside about $20 million for subsidies every year and offered a 30-cent rebate for every square foot of turf removed.

At that price, few homeowners wanted to change their lawns. Even with appliance rebates, there were years when some of the $20 million went unspent.

So MWD took a chance in 2010 and more than tripled the turf rebate to $1 per square foot. And increased it in 2014 to $2 . Other water agencies in Southern California, such as the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, offered as much as $1.75 per square foot on top of MWD’s rebate.

Suddenly it was real money: Homeowners might be able to claim more than $5,000 in rebates for redoing their front yard.

The rebates exploded in popularity. In response, MWD officials quintupled their $20 million budget to $100 million, then added $350 million more this spring. Staff estimated the turf funding would last at least six months; it was all accounted for within weeks. (Of that $450 million, $110 million was set aside for appliance and system upgrades. There is still funding left for these rebates, officials said.)

Every forecast model was wrong, Kightlinger said. Each week was a new surprise.

Public consciousness of the drought was at an all-time high. Every time Gov. Jerry Brown or state water officials made a dire announcement about the drought, MWD had a spike in the number of homeowners calling about removing their lawns.

People finally understood the drought was serious and wanted to help, experts say, but also wanted credit for doing the right thing. Environmental economists say their research has found that people want to be seen making the socially responsible choice, likening lawn replacement to installing solar panels or driving a Prius or Tesla.

A hybrid would be a tougher sell if it looked exactly like a regular car, said Matthew Kahn, a professor at UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

“There are a couple of trends that are intersecting here. Individuals feel a responsibility to be part of the solution, and there’s now greater incentive to go green, and if you think your neighbors are making a similar move, then it’s gotten cheaper in some sense to go green — you won’t stand out,” Kahn said.

Plus, there’s the expectation that water will get more expensive. “I think the typical Californian sees that this drought is here to stay,” Kahn said. “And if there are relatively low-cost actions, like ripping out our grass, these become especially attractive as water prices are expected to rise.”

But critics, such as Keith Lewinger, an MWD board member from the San Diego County Water Authority, say too much ratepayer money has been spent encouraging people to do something that many would have eventually done on their own.

“The MWD rebate was meant as a program to provide an example to people of what could be done. And to help change hearts and minds,” said Lewinger, who acknowledged that, early on, “we did need to kick-start this culture change.”

But that changing mindset, Lewinger said, happened back in April when the governor ordered a 25% cut in urban water use across the state. With a call to action that serious, MWD did not need to put more than $300 million more into rebates, Lewinger said.

“The cultural shift had already happened,” he said.

Officials said turf was the right issue to tackle because Southern California has already made huge strides in promoting water-efficient appliances. In the 1990s, a toilet used up to five gallons per flush. Today, most use less than 1.75 gallons. The appliance rebates now aim to get more toilets under one gallon a flush.

“At the end of the day, 50% of the typical household water is used outdoors,” Kightlinger said. “You’re still going to need to use your toilets, you’re still going to need to shower, you’re still going to need to clean and cook and all those other things. And so yes, doing the devices is more cost effective, but you’re not getting at that other 50% issue.”

There still is work to be done with the indoor half of water savings, such as upgrading washing machines, officials said. Many older, top-loading models guzzle about 40 gallons per wash. Newer, front-loading models use about 14 gallons.

As for turf removal, MWD would like to offer a rebate again next year, but that’s up for debate.

“We obviously can’t afford it at this level,” Kightlinger said. “So we either have to lower our subsidies to a point where it is sustainable and convince the public it’s still worth doing, or find another methodology.”

The turf-removal trend will probably continue, even without the rebates, experts said. With more homeowners replacing their lawns and new state regulations limiting grass for future homes, lush green landscaping will become less fashionable.

Enough people have proven to skeptical neighbors that it is possible to have drought-friendly landscaping that is both practical and beautiful, said Magali Delmas, a UCLA professor who has studied the economics behind what motivates a society to go green.

“I think people really enjoy their lawn once it has been transformed,” Delmas said. “Now you have a completely different landscape that goes with modern homes. There’s more individuality.”

Hoy: Léa esta historia en español

MORE ON THE DROUGHT:

There’s little incentive for L.A. renters to take shorter showers

Look up drought report cards for California’s urban water districts

Hey, California, you can still have a lawn! Here are five water-wise alternatives

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.