Summer was a season to dread, and during the first heat wave in early July last year, the residents of the encampment on Broadway Place had no place to hide.

The sun blazed upon them. The air hardly moved. The sidewalks baked. It would be one of the hottest days in the recorded history of Los Angeles.

An older man complained of dizziness, and his neighbors sat him down. They put a towel on his head and poured water over him.

By midafternoon, temperatures had soared to 108 degrees, and the encampment had its first fatality: Caesar, the pit bull.

He was a familiar presence but had been neglected ever since his owner was stabbed in the neck during a fight and had moved away.

Tied to a jacaranda tree, Caesar had clawed his way into the shadows of a tent, where it was even hotter. The heat killed him. Someone carried his body across the street, and four days later the city’s Department of Sanitation claimed him.

The trauma of his death lingered for days. Weariness was in the air, along with the smell of sweat, urine and moldering trash. Crushed cockroaches dotted the sidewalk.

“This going to be a crazy summer, like all the summers,” Big Mama said. “Tragedy happens on this block. It never fails. It never fails.”

Big Mama, 51, tried to keep everyone in line on the street, but it was getting more difficult.

Even as she kept her appointments for getting housed — sorting out her identification, income and a background check — she had watched smoke rise from a nearby tent fire, felt the glare of business owners and scrambled to stay clear of the Sanitation Bureau as crews swept through the encampment with military efficiency.

She had been told that she and her neighbors would be off the street by the end of June and living in their own apartments in a building a couple of miles away.

Except they were still here. Outreach workers said nothing had changed, that the delay was normal, but Big Mama wasn’t so sure.

One evening, in the waning light, she retreated to her tent. Her friend and next-door neighbor, Top Shelf, was playing music on her phone.

The rap “Stranger to the Pain” came up in the queue, with its haunting refrain:

No drugs in the world could heal the pain that I’m feeling …

You a stranger to the pain that a nigga feels …

The repeating beat and words provided a doleful soundtrack for the encampment, where pain came from a life marked by trauma and disregard. This was the status quo.

One afternoon, Wendy, who lived with Horace Lackey on the far end of the block, was cooking chicken on a camp stove inside their tent. The warm scent of onions, teriyaki, garlic and adobo filled the air.

A vocational nurse, she never shared her personal life with her patients and requested that her last name be withheld. “I’ve come to see that black people are — for the rest of the world — like old broken toys that no one wants to buy,” she said.

Nothing, she believed, would change that.

::

Big Mama had lived on the street for nine years. Somehow, she made it work. She had her routine.

- Wake at 5:30 to the sound of Alan Ishii, owner of the machine shop across the street, as he draws the lock and chain through his driveway gate.

- Shower on Mondays at the shelter where the mobile bathing facility parked.

- Launder clothes at the Sunshine Coin-Op Laundromat at 42nd Street.

- Be careful what you give to others; otherwise you might be broke or hungry near the end of the month.

She was weary of it all, and she knew the city wanted to get rid of her and her neighbors. Sanitation sweeps made it hard enough, and businesses were fencing off the sidewalks. It was only a matter of time until everyone would be pushed out.

Earlier in the year, Big Mama had made two trips to the city Housing Authority on Wilshire Boulevard, one to submit paperwork and another to pick up a Section 8 voucher. It brought a smile to her face and tears to her eyes. But when she applied for an apartment, the manager never called back.

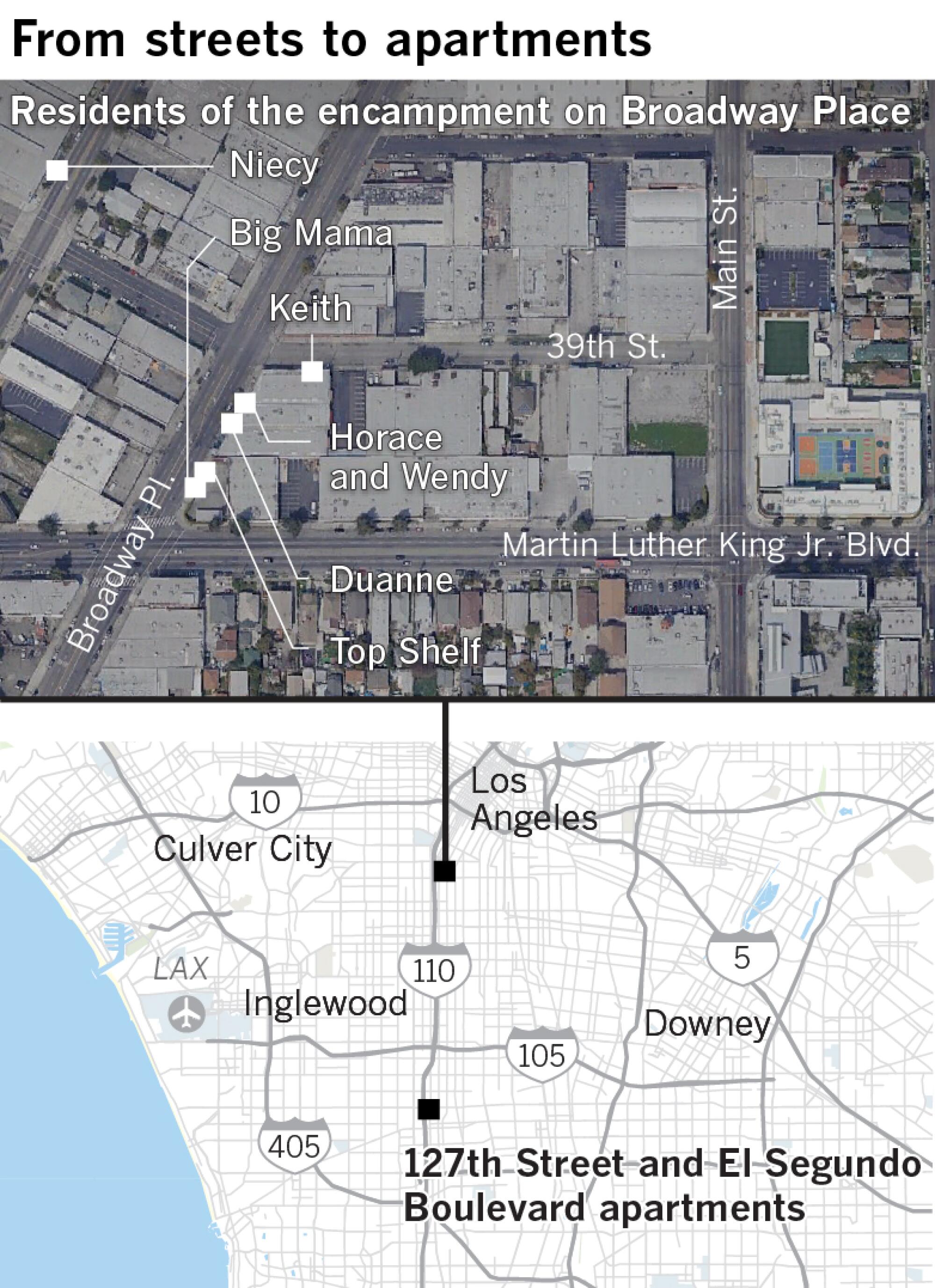

So she agreed to participate in the Encampment to Home program, an initiative of city and county agencies to move homeless residents in South L.A. into housing. One day, mid-May, she joined about 35 other people who had been living on the street for preliminary interviews at a homeless agency.

Melissa Vollbrecht, a program director with the People Concern, helped run the meeting. With pens sticking out of her hair bun, she shouted instructions. She was young, savvy and slight. Big Mama and Top Shelf called her Itty-Bitty. She personified the energy and enthusiasm needed for this work.

Construction was almost finished on two apartment buildings, 160 units, half of which had been set aside for residents in two neighborhoods of encampments around Broadway Place and Leimert Park. Once documents were completed, signatures and subsidies secured, they were told they could move in.

The interviewees crowded into a small conference room and pored over paperwork.

Pencils in hand, they answered questions about their income and personal history. They had done this before. Their faces were shadowed with wariness.

Then Big Mama lost it. Impatient with the process, she stormed out of the room.

Vollbrecht followed her into the parking lot, but Big Mama brushed her away.

“No, I don’t want that,” Big Mama said. “I’m moving on.”

She disappeared into the streets.

::

Nearly a month went by before Big Mama changed her mind. One morning in June, she joined her neighbors on a trip to the apartment complex, where Housing Authority staff would review still more paperwork.

Located at El Segundo Boulevard and 127th Street, the two buildings were in Harbor Gateway, a narrow strip of city land leading to the Port of Los Angeles. Once an oilfield filled with rusty pipes, old wells and storage tanks, the site was cleared in 2017, and new construction began.

Four stories tall with offset planes, picture windows — and for the safety of the residents, no balconies — the buildings stood out from the neighborhood’s older apartments.

Big Mama took a moment to explore what she believed would be her new home.

On the ground floor were computer and exercise rooms, a commons for community gatherings and offices for management and the People Concern, whose counselors would help residents adjust to living indoors.

Big Mama opened an entrance to an unfinished stairwell. The air was dusty from sanding, and the walls smelled of paint. Upstairs, paper covering the floor crinkled under her feet. She stepped around workers studying blueprints and called out apartment numbers as she went by.

“206, 204 …”

She found the unit she had been assigned. She didn’t have a key, but she saw enough to imagine her future, and her knees went weak. “Oh, my goodness!” she said. She placed her palm on a closed door. “Hi, baby! Bless your home, Jesus!”

She rang the doorbell and relished the simple bing bong.

In a community room crowded with six round tables, scattered laptops and folders of paper, an eligibility interviewer sat with a big man known on the street as X — as in extra large. His name was Duanne Hardaway. He was 44. He weighed 368 pounds and stood 6 feet 3. A tattoo on his left arm said XL.

X had been homeless for most of his life, starting when his father threw him out as a teenager. At first, he squatted in abandoned buildings. Court records showed that he’d been convicted of petty theft, reckless driving and “inflicting corporal injury.”

He had tried to turn things around. He said he once had a maintenance job at Universal Studios, but one day high blood pressure and diabetes left him with fuzzy vision and a weakness on his left side. He wasn’t able to continue working.

His housing file — some two dozen forms — was fanned out across a tabletop, but something was wrong. His “chronically homeless” certification was incomplete.

Vollbrecht stepped in and added her signature. X pursed his lips, trying to keep his happiness in check.

“Smile!” the interviewer said. “This is a good day for you.”

X stepped into the courtyard and found an open door to a one-bedroom unit where an electrician was working. X walked in. He saw the dishwasher, the stove, the refrigerator, the new countertops and the bathroom. He pulled out a handkerchief and wiped his eyes.

“I can’t ask for nothing after this,” he said.

In the courtyard, Big Mama spotted a barbecue grill. She pronounced her intention to cook something for the whole complex.

“I’m near the finish line,” she said. “I damn near gave up.”

::

As Big Mama and her neighbors anticipated moving, they began to daydream about life off the streets.

“This is going to be a great day,” she said, “when I’m out of my tent and ain’t living in no fishbowl.”

Top Shelf, 46, was looking forward to spending time with her grandchildren.

She and Big Mama joked about their “take me away” moment. That would be when both of them settled into their apartments and took a bubble bath.

“Take me away!” they sang together with a laugh. It was a parody of a TV commercial for Calgon bath beads.

Leneace Pope, Niecy for short, dreamed of leaving the drama of the streets. She once had been Big Mama’s and Top Shelf’s friend and neighbor but had grown tired of the gossiping and moved a block away.

She pitched her tent against a building. The last resident in that spot — a woman who held off the advances of some men — had been burned out. Gray paint on the side of the building was still sooty and peeling, the sidewalk mottled and black.

Niecy, 34, had lived on and off the streets since 2004. She had five children staying with cousins or guardians. She carried a folder filled with memorial programs for her dead relatives and could list half a dozen health conditions including high blood pressure and sleep apnea.

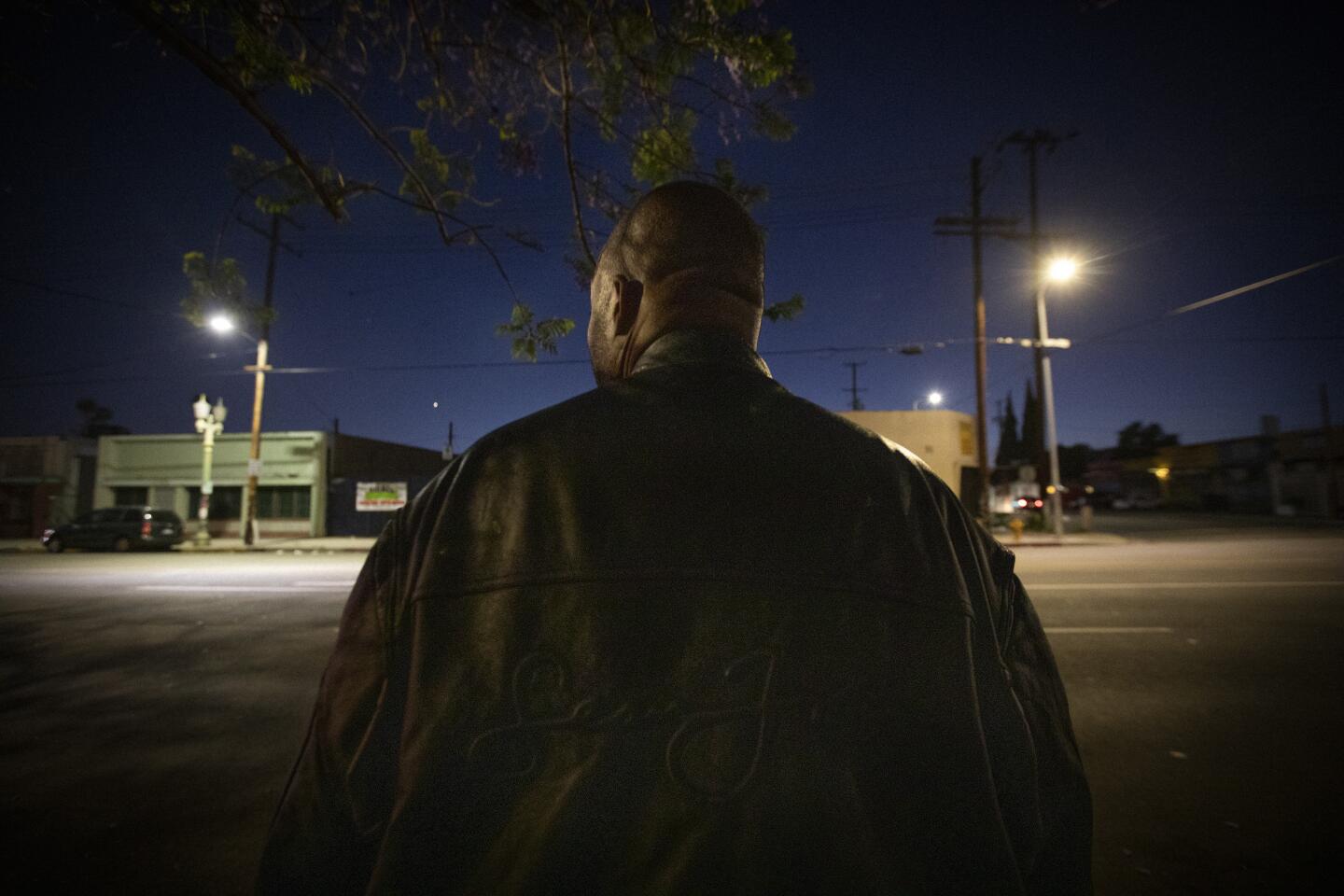

X, too, had his dreams, a life away from the slow burn of anxiety that kept him alert and wary, his eyes always assessing movement in the encampment.

He imagined the first few days in his apartment watching cartoons — “The Flintstones,” “The Jetsons” — to help him relax.

He hoped his son and daughter could one day move in with him.

Around the corner on 39th Street, Keith Gaston wondered what his apartment would be like.

Keith had one of the more palatial tents, tricked out like an in-home theater, with lounge chairs, a television, a space heater and a tangle of extension cords for electricity he had bootlegged.

But at 54, Mr. Key-Key — as his arm tattoo read — was a haunted man.

Growing up in Watts, Keith had run with the Crips. Since then, according to court records, he had convictions in California and Nevada for driving an unregistered vehicle without a license, cocaine possession with intent to sell and other offenses.

He once settled down and got married. He and his wife, Kathy, had two daughters, Kaila and Keyshanna, but soon Kathy began suffering symptoms of cerebellar ataxia, a genetic disorder that affected her brain.

His two girls had inherited it as well. Kathy died; then Kaila, just months after her 21st birthday. Keyshanna was in a long-term care facility in West Covina.

“They had short lives,” Keith said. “And they’re not supposed to have short lives.”

Once in his new apartment, he said, he planned to go back to church. His prized possession was his Bible. He wanted to learn more about the wicked: “So I will know them when I see them.”

::

By mid-July, the mood on the street had soured.

Wendy, the vocational nurse who lived with Horace Lackey, criticized the Encampment to Home interview process for failing to appreciate the humanity of homelessness.

“It’s all paperwork and numbers,” she said, describing a grinding bureaucracy that was laying bare their personal lives.

Wendy, 40, didn’t give the outreach workers her information. She valued her privacy too much. She planned to follow Horace, and if she couldn’t move in with him, she’d live with a relative.

She took a bus to hospice jobs to help the dying.

“Being homeless,” she said, “is my spiritual journey.”

She and Horace had met three years earlier when she was caring for an uncle who lived on the streets. Wendy said she was an alcoholic: “I drained my own spirit, like snakes growing out of your own skin.” After waking up in a house in the Hollywood Hills and not knowing how she got there, she quit drinking.

Horace, 64 , had a similar story. On Nov. 16, 2012 — a date he clearly remembers and is corroborated by court records — he was picked up for possession of a controlled substance and later convicted.

The story of that life is captured in a large tattoo on his back of a horse-headed man smoking a blunt and carrying a gun. Inked near his shoulders were the Gothic letters ICG — Insane Crips Gang.

After his arrest he wised up, and seven years later he is proud of his sobriety.

“Police,” he said, “are God’s angels.”

Like Wendy, he spent his days working. He took a bus from his tent to the Goodwill at Beverly and Fairfax. When he was let go from that job, he started at Big Lots in Inglewood.

“I’m comfortable,” Horace said of life in his tent. “But I’m not comfortable.”

::

Word came with only four days’ notice.

Keith, Niecy and Horace would be moving on Aug. 6. The county agencies that provided their subsidies were satisfied with the latest building inspection. But Big Mama, Top Shelf and X would have to wait. The federal agency that issued their vouchers required a more rigorous review of the apartments.

Hearing the news, Keith got chills. Horace pumped his fists, and Niecy giggled. “I am so ready to go,” she said. “I want to cry, but it ain’t hit me yet.”

That morning, outreach workers wearing T-shirts touting Measure H, the tax initiative that supported their efforts, helped load belongings into a rented U-Haul truck.

By early afternoon, everyone crowded into the community room at the apartments and huddled over blue folders that said “Welcome Home.” Inside was a lease packet with a stack of papers to review, sign and initial, many times over.

Niecy tried to pay attention, but she started to doze. She perked up when Joe Buscaino, the local city councilman, started to speak.

“Let me say you are no longer homeless,” he said.

The room broke into cheers and clapping.

“We love you,” Buscaino said. “We bless you, and just to let you know you are not alone, you will have services here on site every single day so you do not go back out there and live on the sidewalks or in your cars. … Thank you for not giving up.”

The apartment managers began handing out keys.

Niecy stepped up and waved hers in her hand.

She went straight to her unit. She put the key into the lock. Through the open door, a cool breeze from an air conditioner washed over her.

Two boxes labeled “Life Start-Up Essentials” were on the kitchen table, one filled with dishes, pots and pans, the other with linens.

As she wandered through the two rooms and the bathroom, her eyes widened.

“Oh, this is big. Oh, my goodness!” she said. “I thought this was never going to happen.”

She reached for her phone.

“Grannie,” she said, “I just got my keys.” Pause. “It’s nice.”

On her first night in her new home, she took a bath, adding a little bleach and rubbing alcohol to the water. She locked the door, smoked two blunts and had some Moscato wine.

In his unit upstairs, Horace settled in and then texted Wendy, who had taken a bus to her work, with a video of the apartment. Then he turned on the television. Football season was only a month away.

Across the courtyard, Keith stood at the door of his apartment with his mother, Claudia Gandy. She had joined him, and when he offered her the key, she shook her head.

“This is all yours, baby,” she said.

He opened the door, and they stepped inside.

“I prayed so hard for him,” Gandy said.

Excited and uncertain, Keith asked his mother if she thought he could bring his daughter Keyshanna from her long-term care facility for a visit.

His mother tried to settle him down, but Keith paced from room to room and circled the kitchen table.

“Look at what God gave you,” she said.

“I am, Mama,” he said.

::

Big Mama, Top Shelf and X looked out on the street.

“We’re running out of patience,” Top Shelf said.

“We gotta try to have a little more strength,” Big Mama said. “The first shall be the last....” She had been one of the first on Broadway Place, so she would be the last off Broadway Place.

But that was little solace. She grew tired and irritated. She had broken out in a rash. There had been yet another car crash on Broadway Place. Her nerves were rattled.

“I have no more energy for any of this,” she said.

At the beginning of September, her frustration had turned to anger.

“I’m just out here every day and every night,” she said. “It’s a feeling I can’t explain. I feel like I’m forgotten.”

X heard rumors that all of the apartments were full and that anyone still on the streets would have to be assigned to another building near La Brea.

He tried to contain his disappointment. “If I let the streets upset me,” he said, “then I feel that I let the streets win.”

But with some residents gone and others remaining, life was out of balance, and the rules that Big Mama had tried to enforce were being ignored.

Then the Sanitation Bureau posted a notice for another sweep.

Big Mama couldn’t believe it. She would have to drag her tent across the street again. “It can’t make it,” she said.

Two days later, the convoy of trash trucks returned. Big Mama refused to move her battered tent, and this time the police allowed it to remain. She and Top Shelf retreated across the street and watched as X waited for a break in the traffic before hauling his stuff out of the way.

A Kubota with a bucket claw rolled off a flatbed truck. It maneuvered onto the sidewalk and began gnashing on an old sofa. A cleaning crew raked debris toward 39th Street.

Water bottles, scraps of clothing, shoes, food containers, pots, a stuffed Target bag, food seasoning, cardboard, books and papers fanned into the street. Used syringes, collected from a tent on the corner, halfway filled a five-gallon bucket.

Afterward, before anyone could move back to their customary places, the owner of a business on the corner began stringing a green garden fence on 39th Street to block the sidewalk.

Within days, a more permanent chain-link fence was in place. Big Mama felt it was only a matter of time before her sidewalk would be closed off as well.

One morning on the street, God’s Property was belting out “More Than I Can Bear” from a tent up from Big Mama’s.

I’ve been broken into pieces

Seen lightnin’ flashin’ from above

But through it all I remember

That He loves me

Sweet a capella voices contrasted with the trash, the flies, the cockroaches and the smell of excrement in the encampment.

Cops came and went. Fears rose and fell. Strangers passed by. Rumors and the alliances shifted like the smell of weed in the wind.

As the others were settling into their new apartments, Big Mama and her neighbors spent days and nights in a slow accretion of rage, twisted logic and sad resignation.

Big Mama was fed up.

“I’ve been nine years on the streets,” she said, “and I’m not coming back. I would die on these streets if I stayed here. I can’t go no further.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.