Could slain boys have been saved? L.A. County revisits response to abuse allegations

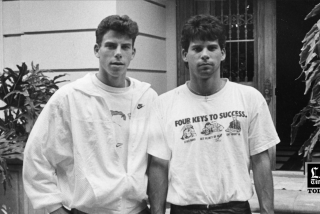

Luiz Fuentes is charged with murder in the deaths of his three young sons. Fuentes has not entered a plea.

A year before three young boys were found stabbed to death in the back seat of a car, their risk of abuse at home had been marked as “high” by a Los Angeles County department’s program intended to guide social workers’ level of intervention.

This week, Los Angeles County’s Department of Children and Family Services officials will convene a high-level review to determine whether social workers made mistakes investigating allegations of abuse and whether the department missed opportunities to save Luis, Juan and Alex, whose father, Luiz Fuentes, is now charged in their deaths.

The brothers, ages 8, 9 and 10, had been the subject of several calls to the county’s child abuse hotline alleging physical abuse by their father. More than a year after the last report, authorities allege, Fuentes fatally stabbed his sons and then stabbed himself.

Fuentes has been charged with murder, and police say he is the sole suspect in the case. He has not yet entered a plea.

Irene G. Nunez, a deputy public defender representing Fuentes, said that the defense is investigating his entire life history and has learned that his father was murdered when he was a small child. Fuentes’ wife, the boys’ mother, died of a brain aneurysm.

“This is such a heartbreaking tragedy,” Nunez said. “His despair and depression basically destroyed everything he loved — everyone he loved.”

DCFS officials have been publicly silent about their findings, and the presiding judge of Los Angeles County’s Juvenile Court, Michael Levanas, has so far declined to release the case records in response to a petition by The Times.

But confidential DCFS case records obtained by The Times indicate that officials believe their initial inquiry has uncovered no egregious errors.

In the weeks since the boys’ bodies were found, social workers and county attorneys have pored over case notes and interviewed witnesses to develop an account of the county’s supervision of the family in the years preceding the deaths.

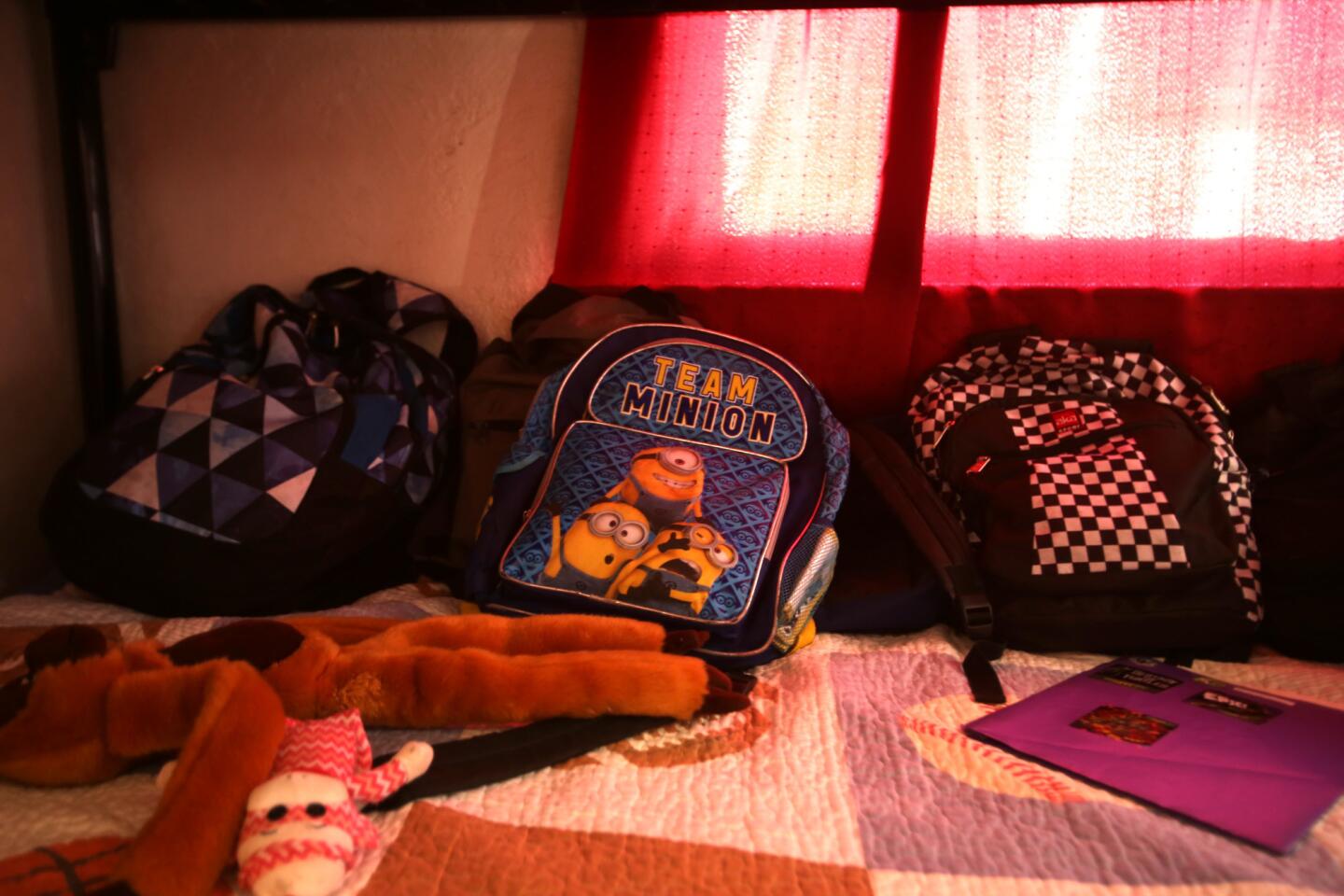

For five years, the family lived with Fuentes’ girlfriend, Josefina Barrales, in her South Los Angeles home. But because of problems between the couple, Fuentes and the boys moved out of the home, Barrales said. They moved in with his sister, then left after a month or so.

After that, he would tell Barrales he was staying in a motel, or sometimes sleeping with the boys in his car, she said.

This is such a heartbreaking tragedy. His despair and depression basically destroyed everything he loved -- everyone he loved.

— Irene G. Nunez, a deputy public defender

Although Barrales, who has a 3-year-old son with Fuentes, maintains there was no abuse in the home, social workers investigated the family three times between 2010 and 2014.

The department’s involvement with the family began in March 2010, when someone called the county’s child abuse hotline to say that Fuentes had struck Luis, then 5, on the face with a belt, according to the case records. Social workers responded, but Fuentes and his sons all denied the allegations and the investigation was marked “inconclusive,” the records say.

Six months later, on Sept. 3, the child abuse hotline received another call from someone who said Luis had shown his teacher a bruise on his stomach that he said was left by his father’s belt. Luis reportedly told the teacher that Fuentes also beat his brothers. County doctors examined the child and determined his bruise came from abuse, the records say.

Juan denied being abused and Alex showed the social worker a light red mark on his arm, but declined to say where it came from, according to the records. The boys were removed by social workers from Fuentes’ care that day and moved to Barrales’ residence, but they were returned to their father on Oct. 27 because of a court order, the records say.

At the time, social workers linked the abuse to Fuentes’ grief over the death of his wife — the boys’ mother — in 2008. Fuentes was ordered by the juvenile court to undergo grief counseling and participate in classes on parenting skills, the records show.

On Nov. 29, 2011, social workers recommended that the case be closed, and a court officer agreed. At that point, Fuentes had completed parenting classes but attended only one counseling session. He blamed his busy schedule for the lapse, court records say.

Now, officials are analyzing whether the department was correct to close the case without more compliance from the father — and whether appropriate treatment of his depression might have helped to prevent his deterioration in later years.

“It is disappointing if those activities were ordered by the judge or agreed by the father but never completed,” said Philip Browning, the department’s director.

Barrales said she doesn’t recall Fuentes taking classes, and in a previous interview with The Times said she believes he was suffering a severe depression. As far as she knew, he had never gone to therapy, despite losing his father at a young age, his mother when he was about 18 years old and later his wife, she said.

DCFS did not record contact with the family again until someone made a call to the child abuse hotline on April 9, 2014, to say that the boys were the victims of physical abuse by their father and emotional abuse by him and his romantic partner, the records say.

The caller said Alex, then 6, had misbehaved in school the day before and his father punished him by striking him on the chest with a belt, the records say.

An initial review by social workers of the family’s case records uncovered no efforts to speak to the boys at school separately from their father. Social workers did not speak to them until an appointment with Fuentes on April 22, when he and the children all denied abuse, and Alex recanted the account that he had previously told his teacher, case records say.

Without confirming that the Fuentes boys were not interviewed separately, Browning said he was frustrated to read case files showing that children are not always interviewed apart from their accused abusers.

“That should be done in every case,” he said.

Barrales confirmed that a social worker visited in April, but said that’s the only visit she recalls.

“There was one occasion, where they thought he’d hit Alex,” Barrales said. “But it wasn’t true … they never found anything.”

A doctor reported no signs of abuse during an August visit and follow-up visits by social workers yielded no signs of anything amiss.

There’s a joke that DCFS is on the cutting edge of 1990. We are still working an antiquated state system of which we have very little control.

— Philip Browning, director of Department of Children and Family Services

Still, in August of last year, social workers calculated the family’s risk with a computer program that is meant to use statistical information to help guide their level of intervention. The program — known as Structured Decision Making — uses a list of multiple choice questions to collect information.

Some of the information submitted by the social worker was incorrect, the records show. The worker, for instance, said the father had never had a previous mental health problem despite the depression documented by social workers in 2010.

The worker also said there was no history of substance abuse, despite a previously acknowledged DUI arrest, case records show.

It is unclear whether the information was available to the social worker, because the department’s computer system was conflating multiple families’ case histories into one, and it was difficult to discern what information applied to the Fuentes family and what information applied to other families, case records say.

“There’s a joke that DCFS is on the cutting edge of 1990,” Browning said. “We are still working an antiquated state system of which we have very little control.”

He noted that the California Department of Social Services is planning to replace the data system, but it is years behind schedule.

Despite the missing information, the Structured Decision Making program recommended that social workers “promote” the case and remove the children or provide services inside their father’s home, the records show. The program scored the children’s risk of abuse as “high.”

Social workers decided to instead “override” the recommendation, and they marked the latest allegation as “inconclusive,” the case records show. The department’s review will analyze whether the decision was appropriate, Browning said.

The department shows no recorded contact with the family after closing its investigation last year until the boys died, according to the family’s case file.

In the months before their death, the boys were homeless and living with their father in his car, case records say. The father and his sons received $204 in food stamps each month, and the father’s June 22 application for CalWorks welfare benefits was denied, case records show.

DCFS social workers wrote that they did not yet understand why the CalWorks application was denied during a period when the family was under such obvious financial distress.

In a previous interview with The Times, Barrales, who worked with Fuentes at the Farmer John meat processing facility, said he had told her shortly before the deaths of the boys that he didn’t have any money.

The DCFS internal review, which will probably take place Friday, is one of several the department has held over the last three years in response to recurrent cases of children dying of abuse and neglect after mistakes by social workers and breakdowns in the rickety computer systems that support them, Browning said.

“The goal is to identify what we might do differently in the future and consider any employee discipline that might be warranted,” Browning said.

[email protected]; Twitter: @gtherolf

[email protected]; Twitter: @brittny_mejia

ALSO:

San Fernando Valley leads the way in lawn-replacement rebates amid drought

Coastal Commission bans captive orca breeding at SeaWorld San Diego

California bullet train project is attracting interest — but not funding

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.