The brothers were a study in contrasts.

Syed Raheel Farook was the extrovert — loud and sociable with an air of nonchalance. Acquaintances said he preferred to walk a casual line when it came to religion. He told people he “wasn’t into Islam,” dated a non-Muslim girl, imbibed freely and showed up at a local mosque primarily to please his family.

After graduating from La Sierra High in Riverside, he joined the Navy and received medals for service in the “Global War on Terrorism.”

The brother two years his junior was soft-spoken and reserved. Syed Rizwan Farook had a reputation for being pleasant but introverted. He enjoyed fixing old cars and shooting hoops. He joined the Muslim Club at school, memorized the Koran and was outwardly devout.

Years ago, he once grew irate when his brother — hair still wet from a shower — requested a few more minutes to ready himself before heading to prayers.

“Rizwan was yelling. He was cursing,” recalled Shakib Ahmed, 32, who was at the house that day and attended the same mosque. “Raheel just said, ‘All right, all right,’ like it was nothing. He was laid-back.”

Although younger, “Rizwan was kind of the boss,” Ahmed said.

The Farook family had come from modest means. Pakistani immigrants, the parents made their way to Chicago, where Syed Rizwan Farook was born. After moving to the Inland Empire, the father worked as a truck driver, while the mother became a clerk at Kaiser Permanente Riverside Medical Center.

Neighbors recall the family keeping chickens, roosters and goats on their property. While raising four children, the couple declared bankruptcy in 2002.

1/106

Friends and relatives of Sierra Clayborn gather for her funeral at Mt. Moriah Missionary Baptist Church in South Los Angeles.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 2/106

A memorial service was held for Nicholas Thalasinos on Saturday morning at the Shiloh Messianic Congregation in Calimesa.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 3/106

A Shabbat service was part of the memorial for Nicholas Thalasinos at Shiloh Messianic Congregation in Calimesa, where Thalasinos and his wife, Jennifer, were integral parts of the congregation.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 4/106

A hired mover carries out personal items from the home of San Bernardino shooters Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 5/106

Residents turn out to greet President Obama’s motorcade in San Bernardino.

(Michael Robinson Chávez / Los Angeles Times) 6/106

President Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama greet San Bernardino Mayor R. Carey Davis, center, and Supervisor James Ramos outside Air Force One at the San Bernardino airport on Friday night.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 7/106

President Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama leave in a motorcade, after arriving at San Bernardino International Airport, to meet privately with the families of the victims of the San Bernardino terrorist attack.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 8/106

President Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama depart Air Force One at San Bernardino International Airport.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 9/106

San Bernardino residents Ashrie Matthews, left, Leah Brown and James Matthews line the street to cheer the president’s motorcade.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 10/106

President Obama stopped in San Bernardino on Friday evening to privately visit with the families of some of the victims of the Dec. 2 terrorist attack. Ashrie Matthews, left, Leah Brown and James Matthews joined others to cheer as the president’s motorcade passed.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 11/106

Anti-Obama protester Deann D’Lean, right, holds some of the many signs she brought to a small protest. In the background, Paul Rodriguez, Jr., with America First Latinos holds a bullhorn. Protesters were out on some San Bernardino street corners voicing their opposition to the president and Islamic State.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 12/106

People continue to visit the memorial just down the street from where the terrorist attack occurred.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 13/106

Family members and friends pay their respects to Robert Adams, one of the 14 victims killed in the San Bernardino shooting, during his graveside funeral service at Montecito Memorial Park in Colton.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 14/106

Summer Adams, center, grieves at the graveside ceremony for her husband, Robert Adams, at Montecito Memorial Park in Colton.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 15/106

A mourner sits on the curb with her head in her hands during the graveside ceremony for San Bernardino shooting victim Robert Adams at Montecito Memorial Park in Colton.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 16/106

Mourners embrace at the funeral for Aurora Godoy at Calvary Chapel in Gardena on Wednesday. Godoy was one of 14 killed in the attack in San Bernardino on Dec. 2. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

17/106

Mourners embrace at the funeral for Aurora Godoy at Calvary Chapel in Gardena on Wednesday. Godoy was one of 14 killed in the attack in San Bernardino on Dec. 2.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 18/106

Mourners arrive for the funeral for San Bernardino shooting victim Aurora Godoy at Calvary Chapel in Gardena on Wednesday.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 19/106

Shemiran Betbadal, mother of Bennetta Betbadal, is hugged by family after funeral services at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Rancho Cucamonga.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 20/106

Pallbearers carry the casket of Bennetta Bet-Badal during funeral services Monday at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Rancho Cucamonga. Bet-Badal was one of the 14 people killed in the San Barnardino shooting rampage.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 21/106

The husband and children of Bennetta Bet-Badal hug Monday following her funeral services at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Rancho Cucamonga.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 22/106

Funeral services were held for Bennetta Bet-Badal, one of the 14 people killed in the San Barnardino shooting rampage, at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Rancho Cucamonga.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 23/106

Funeral services were held for Bennetta Bet-Badal at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Rancho Cucamonga.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 24/106

Funeral services were held for Bennetta Bet-Badal at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Rancho Cucamonga.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 25/106

Twelve days after the mass shooting attack at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino the flowers are beginning to wilt but hugs and paryers are still in abundance.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 26/106

Gwen Rodgers, assistant pastor at the Church of Living God, hugs Cindy Quinones, cousin of the slain Aurora Godoy, during a vigil at the makeshift memorial for the victims of the terrorist attacks in San Bernardino, Calif.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 27/106

Visitors arrive to pay their respects at the makeshift memorial outside the fenced off Inland Regional Center, in the background, the site of the deadly terrorist attacks, in San Bernardino, Calif.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 28/106

San Trinh, the longtime boyfriend of Tin Nguyen, 31, one of the victims of the San Bernardino terrorist attack, is consoled by family members as Nguyen’s casket is loaded into a hearse at St. Barbara’s Catholic Church in Santa Ana.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 29/106

Cousins of Tin Nguyen -- Trang Le, left, Tram Le and Krystal Le -- hold onto some of her personal items and cry as they watch her casket being lowered into the ground at her funeral at the Good Shepherd Cemetery in Huntington Beach.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 30/106

Pallbearers stand guard over the casket of the Tin Nguyen, a Cal State Fullerton graduate, at the start of her memorial service at St. Barbara’s Catholic Church in Santa Ana.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 31/106

Van Thanh Nguyen shouts her daughter’s name during her funeral at the Good Shepherd Cemetary in Huntington Beach. Tin Nguyen was 31.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 32/106

Family members and friends write messages on the side of the Tin Nguyen’s burial vault.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 33/106

Van Thanh Nguyen places her hand on her daughter’s casket while surrounded by friends and family.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 34/106

The casket of San Bernardino shooting victim Isaac Amanios leaves the St. Minas Orthodox Church during his funeral service in Colton.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 35/106

Two women cry during Isaac Amanios’ funeral service at the St. Minas Orthodox Church in Colton. Amanios, 60, is survived by his wife and three children.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 36/106

Funeral goers cry during Isaac Amanios’ service. Amanios had shared a cubicle with the male shooter at the San Bernardino County Public Health Department.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 37/106

Frineds and family stand during the funeral service for Isaac Amanios.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 38/106

Trenna Meins, center with daughters after the funeral for her husband Damian Meins at St. Catherine Of Alexandria in Riverside.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 39/106

Pallbearers escort the casket of Damian Meins at St. Catherine of Alexandria church in Riverside.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 40/106

Mourners gather at St. Catherine Of Alexandria in Riverside on Friday morning for the funeral of Damian Meins, one of 14 people killed in the San Bernardino shooting.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 41/106

Trenna Meins places a cross on her husband’s coffin. Damien Meins was killed in a terrorist attack at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 42/106

Mourners gather for the funeral of Damian Meins.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 43/106

Community members sing Amazing Grace during a candlelight vigil for Nicholas Thalasinos and the 13 other San Bernardino shooting victims at Fleming Park in Colton, Calif.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 44/106

COLTON, CA - DECEMBER 10, 2015: Jennifer Thalasinos,middle, fights back tears during a candlelight vigil for her slain husband Nicholas Thalasinos and the 13 other San Bernardino shooting victims at Fleming Park on December 10, 2015 in Colton, California.(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

45/106

A portrait of Yvette Velasco, one of the victims of the deadly San Bernardino terrorist attacks, is placed at her funeral service at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, in Covina, Calif.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 46/106

Robert Velasco, father of Yvette Velasco, consoles a family member during Yvette’s funeral service at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, in Covina, Calif.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 47/106

COVINA, CALIF.--December 10, 2015 - The coffin of San Bernardino shooting victim, Yvette Velasco, is carried to the hearse following a private viewing for family at Forest Lawn Mortuary in Covina, Calif.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 48/106

An FBI dive team searches a lake located about two miles north of the Inland Regional Center in connection with last week’s terrorist attack and shootout that left the two attackers and 14 victims dead.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 49/106

An FBI dive team searches a lake near the Inland Regional Center in connection with last week’s terrorist attack.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 50/106

A memorial to victims of the terrorist attack in San Bernardino continues to grow near the Inland Regional Center, where the attack took place during a holiday party.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 51/106

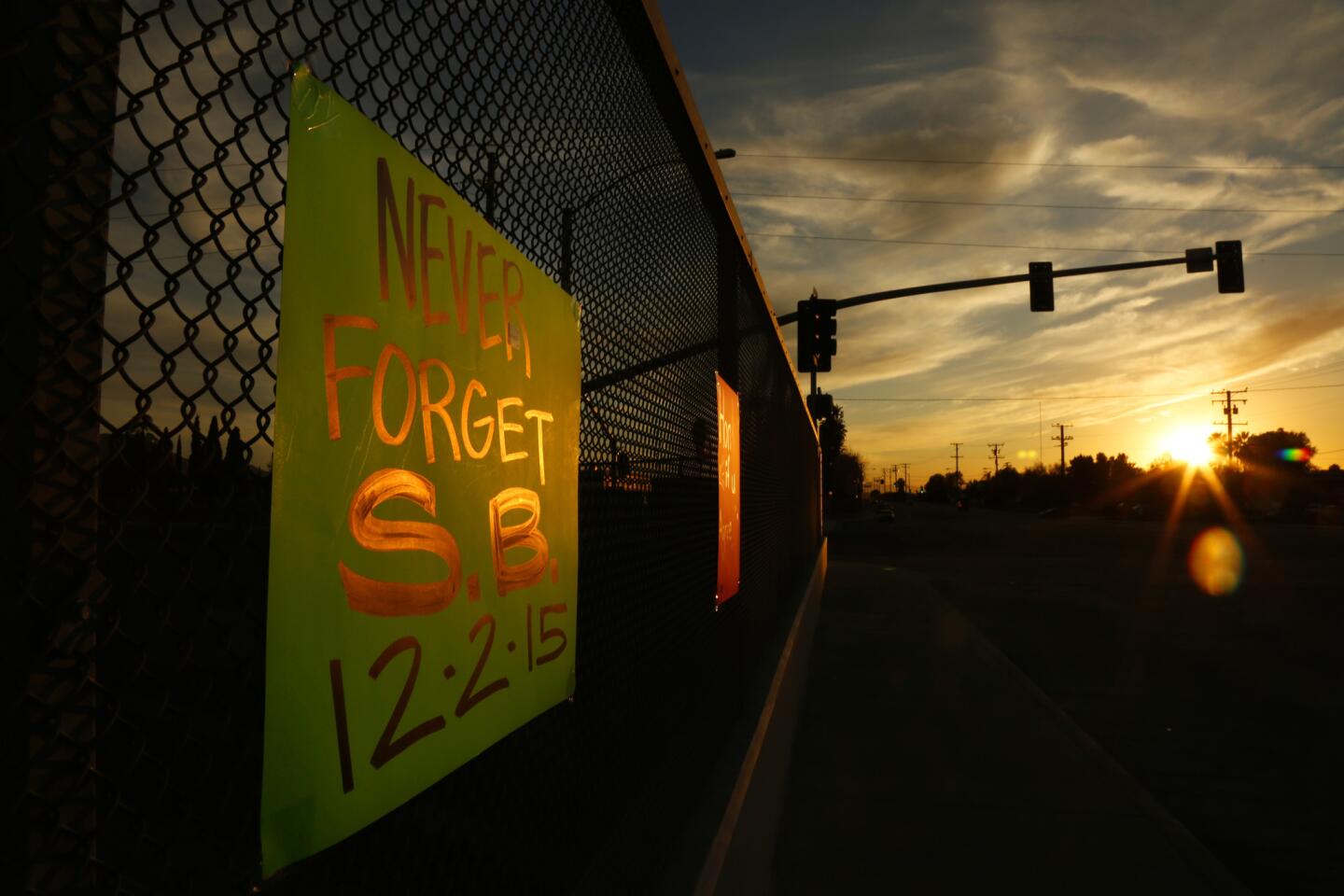

One week after the mass shooting at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino, the public is posting signs of gratitude and thanks like this one found at the San Bernardino Police Department.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 52/106

Family members and survivors paid their respects with a moment of silence at 11 a.m., exactly one week after the shooting occured at the Inland Regional Center.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 53/106

Customers wait for the doors to open at Turner’s Outdoorsman in San Bernardino Wednesday morning.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 54/106

Speaking during a Dec. 8 news conference, dispatcher Michelle Rodriguez of the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department becomes emotional as she recounts the events of the deadly San Bernardino attack.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 55/106

Trenna Meins, right, of Riverside, hugs friends and family during a vigil t the Riverside County Health Complex for her husband, Damian Meins, and 13 others killed in the San Bernardino shooting rampage.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 56/106

On Dec. 8, people bring flowers, candles and remembrances to a memorial to the San Bernardino shooting victims near the Inland Regional Center, the scene of the attack.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times) 57/106

Frank Cobet of the Get Loaded gun store in Grand Terrace shows a customer an AR-15 rifle on Dec. 8.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 58/106

Monica Gonzales relights candles Tuesday morning at a memorial for victims of the shooting rampage in San Bernardino.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 59/106

Community members and students gather for a Dec. 7 vigil on the Cal State San Bernardino campus to remember the victims of the deadly attack in the city.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 60/106

Patricia Corona of Colton, Calif., holds her children, Dejah Salvato, 7, and Brandon Salvato, 9, as they attend a Dec. 7 vigil at the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors headquarters to pay tribute to the victims of the city’s recent mass shootings.

(Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) 61/106

A prayer is said at the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors headquarters to honor the victms of the city’s recent mass shootings.

(Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) 62/106

FBI agents put up a screen to block the view of onlookers as they investigate the building at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images) 63/106

Syed Farook, father of the suspect in the San Bernardino mass shooting, Syed Rizwan Farook, arrives at his home to a swarm of reporters in Corona, Calif.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 64/106

Roses are laid at the entrance to San Bernardino County headquarters as thousands of employees returned to work Monday, five days after Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik opened fire on a gathering of his co-workers, killing 14 people and wounding 21.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 65/106

Trudy Raymundo, director the the San Bernardino County Department of Public Health, is surrounded by San Bernardino County supervisors as she addresses the media during a press conference Monday.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 66/106

John Ramos of Riverside pays his respects Monday at a makeshift memorial site honoring Wednesday’s shooting victims in San Bernardino.

(Jae C. Hong / Associated Press) 67/106

Claudia Zaragoza writes a message on a banner at the ever-growing memorial site to the victims of the recent mass shootings near the Inland Regional Center.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 68/106

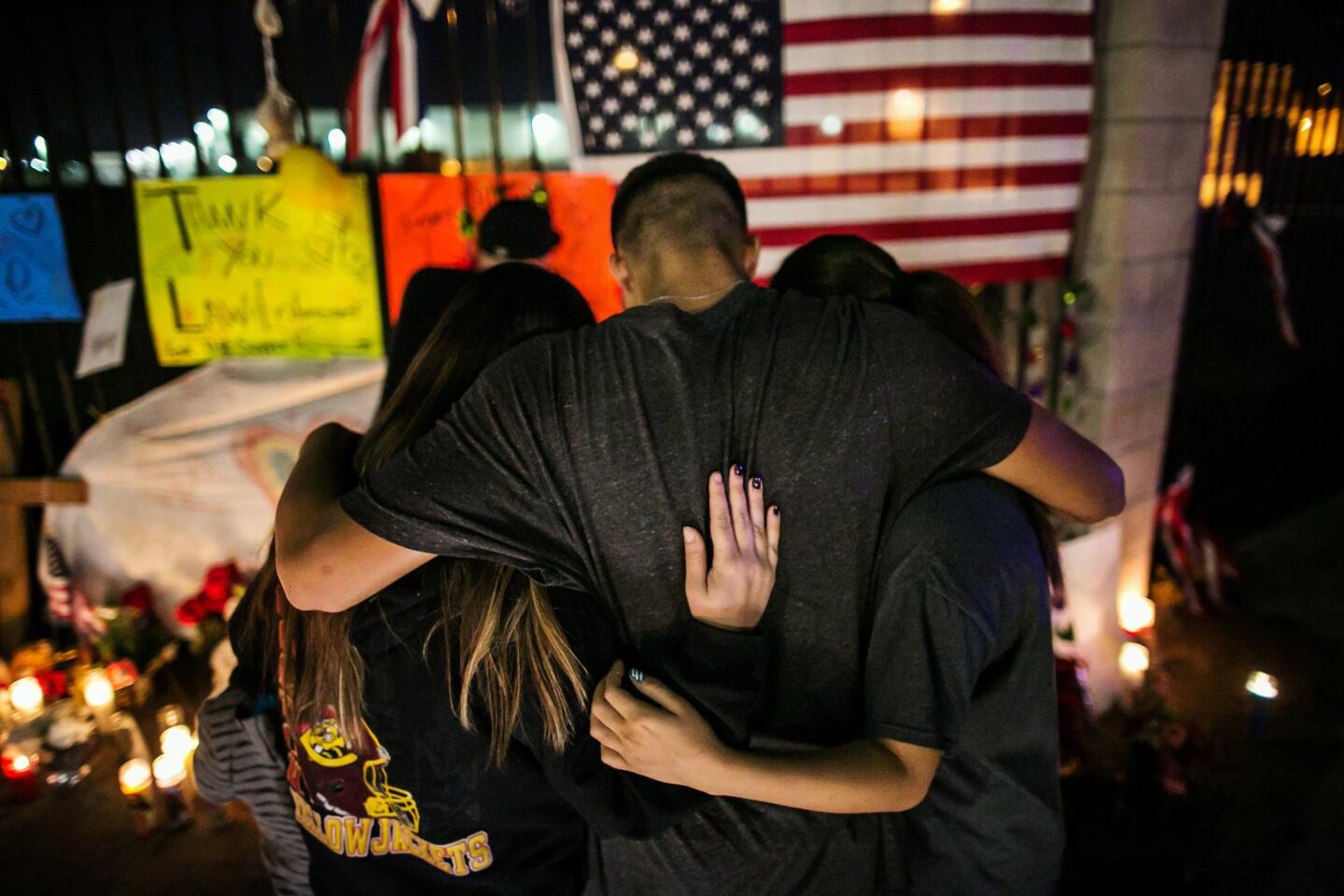

Caroline Campbell, from left, Jessie Campbell and Rylee Ponce embrace as they pay their respects at the ever-growing memorial site for the victims of the recent mass shootings.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 69/106

Caroline Campbell embraces her son, David Malijan, 6, as they pay their respects at the ever-growing memorial site to the victims of the recent mass shootings near the Inland Regional Center.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 70/106

The Zafarullah family of Chino, originally of Pakistan, watches Obama’s address. Arshia, at left, is holding her 18-month-old nephew, Sohail Ahmed.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 71/106

One of several signs supporting the city of San Bernardino hang above the 215 Freeway on Sunday evening.

(Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) 72/106

Members of the Muslim community, such as Khadija Zadeh, lit candles and wrote messages to the families of victims of the San Bernardino shooting rampage during a memorial service at the Islamic Community Center of Redlands in Loma Linda.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 73/106

Ajarat Bada prays during a memorial service at the Islamic Community Center of Redlands in Loma Linda to remember the victims of the San Bernardino shooting rampage.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 74/106

Alaa Alsafadi, center, holds her son, Yousef, 4, during a memorial service at the Islamic Community Center of Redlands in Loma Linda.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 75/106

Riders from the Christian Motorcycle Association in San Bernardino pray at a growing makeshift memorial for San Bernardino shooting victims near the Inland Regional Center.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 76/106

A candlelight vigil dubbed “United We Stand,” took place at Granada Hills Charter High School on Saturday evening. The event was organized by Muslim Youth Los Angeles and Devonshire Area in Partnership.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 77/106

Ryan Reyes, boyfriend of San Bernardino shooting victim Larry Daniel Kaufman, hugs members of Dar Al Uloom Al Islamiyah of America mosque who brought roses to a memorial at the Sante Fe Dam on Saturday.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 78/106

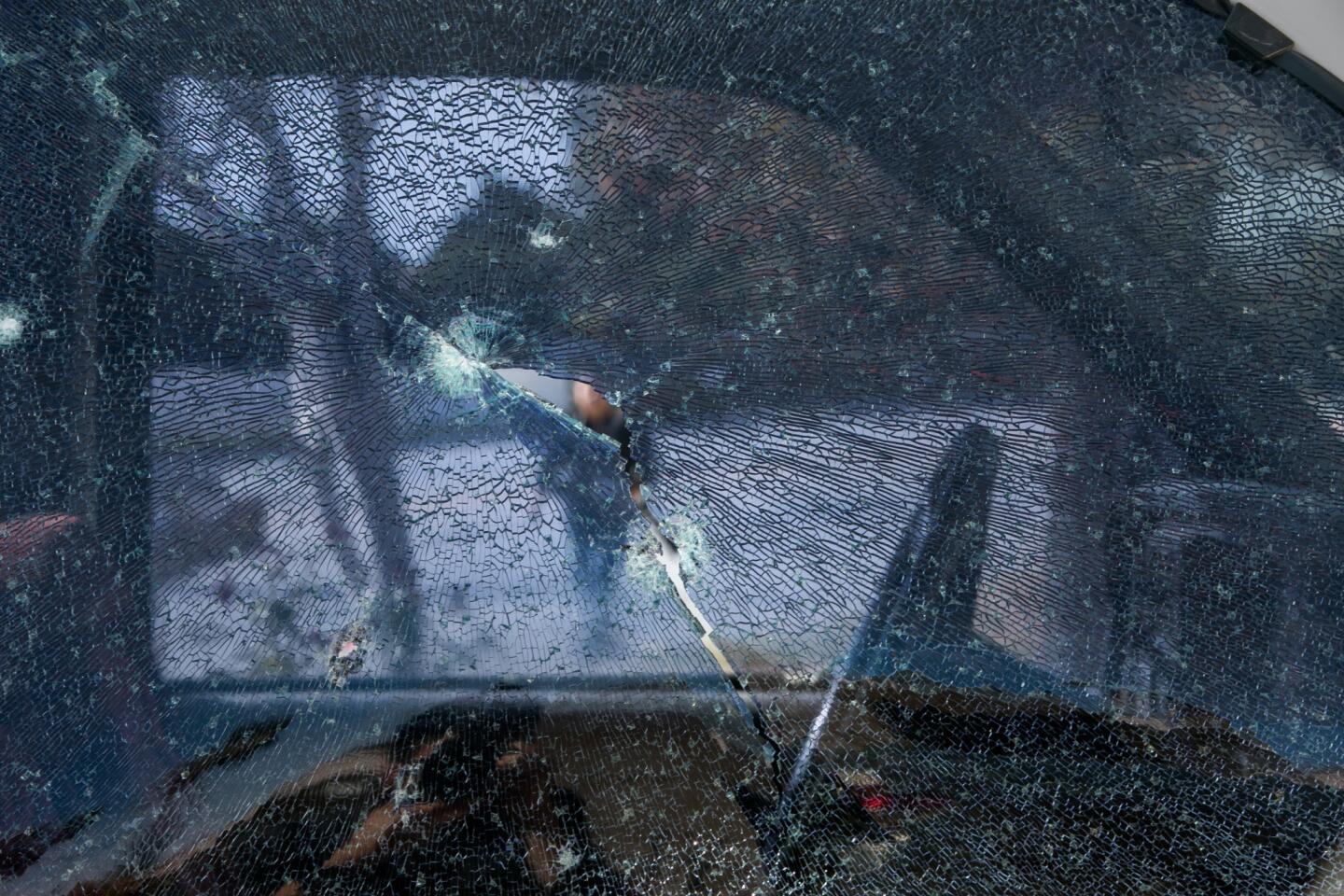

A bullet hole in the window of a pick up truck where the shootout took place on San Bernardino Avenue.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 79/106

A composite photo of the 14 victims of the San Bernardino shooting rampage. (Courtesy of family / Los Angeles Times)

80/106

People kneel in prayer for victims of the recent mass shootings at the Inland Regional Center, in San Bernardino.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 81/106

After sunset, people continue to arrive at the memorial site for the victims of the recent mass shootings at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 82/106

The scene after landlord Doyle Miller opened the doors and allowed the news media inside the Redlands town home where Syed Rizwan Farook and Tafsheen Malik, suspects of the deadly the recent mass shootings in San Bernardino, lived.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 83/106

Josie Ramirez-Herndon, center, and her daughter, Chelsie Ramirez, bottom left, join other community members as they pray during a candlelight vigil.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 84/106

Fabio Ahumada, a San Bernardino EMT, attends a vigil at San Manuel Stadium

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 85/106

A couple embrace at the candlelight vigil to honor the victims of the mass shootings at the Inland Regional Center.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 86/106

Angel Meler-Baumgartner 11, who was a member of the Inland Regional Center, where the shooting occurred, attends a vigil at San Manuel Stadium for the victims.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 87/106

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community USA held a press conference and prayer vigil at Baitul Hameed Mosque in Chino. The group denounced the massacre.

(Michael Robinson Chávez / Los Angeles Times) 88/106

Amy Mahmood, right, holds hands with a woman named Shenaz during the vigil at San Manuel Stadium.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 89/106

Ryan Reyes, center, breaks down after finding out his boyfriend of three years, Daniel Kaufman, 42, was one of those killed during Wednesday’s mass shooting at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino.

(Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) 90/106

Ryan Reyes holds an image of his boyfriend Daniel Kaufman who was confirmed as one of the 14 victims of Wednesday’s mass shooting at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino.

(Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) 91/106

Larry Jones, left, pastor of Crossover Outreach Church; Dr. Jeannetta Million, pastor of Victoria’s Believers Church; and Arnold Morales, pastor of King of Glory Church, pray for the victims and those involved in the mass shooting in San Bernardino.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 92/106

A coalition of church leaders comes together to pray for the victims and those involved in the San Bernardino shootings.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 93/106

FBI investigators inside the suspects’ Redlands home on Thursday morning.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) 94/106

The investigation continues Thursday morning on San Bernardino Avenue, where two suspects in the mass shooting at the Inland Regional Center died in a shootout with police.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) 95/106

Law enforcement stands guard at a police line as investigators work at a Redlands home after the San Bernardino attack.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 96/106

A SWAT team stands guard with a rifle pointed at a home that is being investigated by police after today’s San Bernardino’s mass shootings.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 97/106

Farhan Khan, second from right, who was identified as the brother-in-law of San Bernardino shooting suspect Syed Rizwan Farook, joins religious leaders during a news conference at the Council of American Islamic Relations in Anaheim.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 98/106

San Bernardino County sheriff’s deputies draw guns behind a minivan on Richardson St. during a search for suspects involved in the mass shooting of 14 people at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 99/106

Marie Cabrera, Sonya Gonzalez and Christine Duran, all of San Bernardino, pray after the mass shooting in San Bernardino.

(Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) 100/106

A woman and a man enter the Rudy C Hernandez Community Center after they and other people, who were at the scene of a mass shooting, arrived by bus to be reunited with their familys.

(Hayne Palmour IV / San Diego Union-Tribune) 101/106

Emergency personnel bring in a wounded person into Loma University Medical Center after the shooting in San Bernardino on Wednesday.

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 102/106

A SWAT unit is on the move in San Bernardino.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 103/106

A member of the San Manual Fire Department takes the names of people evacuated from the scene of a mass shooting in San Bernardino before they are loaded onto buses and taken away from the area.

(Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) 104/106

Sheriff’s department SWAT members deploy on Richardson Street in San Bernardino on Wednesday.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 105/106

Sheriff’s department SWAT members deploy near San Bernardino Avenue and Richardson Street in San Bernardino on Wednesday.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 106/106

Evacuated workers join in a circle to pray on the San Bernardino Golf Course across the street from where a shooting occurred at the Inland Regional Center.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) Life at home was turbulent. In court records, Rafia Farook detailed a violent marital history in which her children often had to intervene.

In 2006 divorce filings, she said her husband of 24 years was physically and verbally abusive. She referred to him as a negligent alcoholic and said his hostility had forced her and the children to move out.

Later, in multiple requests for domestic-violence protection, the mother detailed the maltreatment she said she encountered and that her children witnessed: Her husband — also named Syed — had dropped a TV on her while he was intoxicated. Another time, he pushed her toward a car. After a drunken slumber, he shouted expletives and threw dishes in the kitchen.

“Inside the house he tried to hit me. My daughter came in between to save me,” she said about one incident.

She also said her husband was suicidal and described a February 2008 incident when he threatened to kill himself. She called her husband’s brother in Chicago, who notified local police. They alerted Riverside authorities, who arrived at the home. Her husband was placed in a county hospital for a 72-hour observation period, she said.

A neighbor said the Farooks kept to themselves. If there was fighting, it took place behind closed doors, said Rosie Aguirre. The mother, she said, appeared to be very much the head of the family.

“Bossy, to put it lightly,” said Aguirre, who has lived in the neighborhood for two decades.

Working part time at the hospital for $16 an hour, Rafia Farook sought custody of the couple’s teenage daughter, Eba. She proposed that her son Syed Rizwan Farook supervise future visits between her husband and daughter.

In April 2008, Rafia Farook halted divorce proceedings. But one month later, she filed a petition for legal separation, citing irreconcilable differences. Her husband, she said in court papers, had not held a steady job for “a long time.” They divorced earlier this year.

Despite bearing witness to an unstable marriage, Syed Rizwan Farook seemed intent on settling down. His online dating profile said he was looking for someone who took his Sunni Muslim faith seriously. He had studied environmental health at Cal State San Bernardino and taken a job with the county. He didn’t drink or smoke and was growing out his beard.

He brought Tashfeen Malik to the United States on a fiancee visa last year. Family members said they were not “overly close” to the 29-year-old woman who had been born in Pakistan and raised in Saudi Arabia. They never even saw her face, since Malik wore a niqab, which revealed only her eyes.

“She was totally covered,” said one of the family’s attorneys. “They just knew her as ‘Syed’s wife.’”

In the aftermath of last week’s deadly act of terror that killed 14 people at the Inland Regional Center, the Farooks have found themselves fielding an extreme amount of attention and scrutiny. Family members were held for hours — grilled about the gunman and his wife’s social media activity, affiliation with religious sects, changes in behavior and dress, and possible proselytizing. FBI agents demanded a list of guests at the couple’s Saudi Arabia wedding as well as their local reception.

The night of the shooting, Farook’s brother-in-law offered a universal sentiment: “Why would he do something like that?” he said.

Attention has also turned to Farook’s 30-year-old brother, whose wife’s sister is married to a friend who bought two of the semiautomatic rifles used in the attack. Three days after the shooting, police were called to Syed Raheel Farook’s Corona home after an unidentified woman reported a domestic disturbance. A spokesman for the Riverside County district attorney’s office said the office was reviewing the case.

Until a few weeks ago, Syed Rizwan Farook regularly stopped by his brother’s home for Sunday dinners, said a neighbor who lives two doors down. The brothers’ father had moved in with Syed Raheel Farook and often baby-sat his child.

“He’s really nice, very talkative,” said Brittani Adams, 24, about the father.

The father struck up a conversation with Adams’ husband, admiring the gold 1970s Jaguar in their driveway. He mentioned that his other son had a penchant for repairing cars. About a week ago, Adams said she noticed that large boxes and furniture were being loaded out of the house and into vehicles at night.

After the shooting, an Italian newspaper ran a story that said Farook’s father said his 28-year-old son agreed with the ideology of Islamic State leaders and was “obsessed” with Israel.

But a family spokesman said the elder Farook did not recall making that comment. The spokesman, Hussam Ayloush, executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations in the Los Angeles area, added that the father was stressed and on medication.

His ex-wife had lived with Syed Rizwan Farook and Malik in Redlands.

“It stretches the imagination to believe that she didn’t have some kind of knowledge … about what was going on,” said Sen. James E. Risch (R-Idaho), who reviewed information on the shooting.

The morning of Dec. 2, the couple left their 6-month-old daughter in Rafia Farook’s care. At about 11 a.m., the shooting began.

[email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]

Times staff writers Kate Mather, Jack Dolan and Paloma Esquivel contributed to this report.

ALSO

Shooting closure hits Inland Regional Center’s clients hard

San Bernardino shooters planned bigger attack, investigators believe

Loan to San Bernardino shooter draws scrutiny to online lending industry

Survivors and victims’ family members help California Democrats put a face on gun violence