What will Los Angeles transportation be like when the Olympics arrive in 2028?

Three rail projects will be crucial to Los Angeles hosting the 2028 Summer Olympics.

As the 1984 Summer Olympics approached, few questions loomed larger in Los Angeles than traffic.

The region, a rail transit dead zone, was already notorious for gridlock. Southern California’s extensive streetcar network, once the largest in the world, had been ripped out decades earlier. And the ribbon-cutting on the first modern rail line was still six years away.

But for all the anxiety about apocalyptic congestion, traffic during the 1984 Olympics was painless, thanks to a vast public effort to reduce congestion. Angelenos telecommuted or worked flexible schedules, public transit agencies ran an extensive network of shuttles, and trucking companies changed their delivery schedules to avoid peak hours.

The

A new sales tax increase approved by Los Angeles County voters in November will fund another massive transit expansion, enhancing bus service and bringing rail lines to the Sepulveda Pass, the San Fernando Valley and cities southeast of downtown

“In 1984, we had bupkis in terms of rail,” said Dave Sotero of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. “Now, we’re going gangbusters.”

Los Angeles Mayor

Many of the key Olympics event locations — USC, downtown and Santa Monica — are already connected to the Metro rail network. By 2028, stations are slated to open within a mile of several more venues, including UCLA and Inglewood.

Other rail projects in the works are aimed at improving rail travel for Angelenos and out-of-town visitors.

Here’s a look at three rail projects that officials say will enhance the region’s transit network before the 2028 Olympics.

2021: A seamless ride through downtown

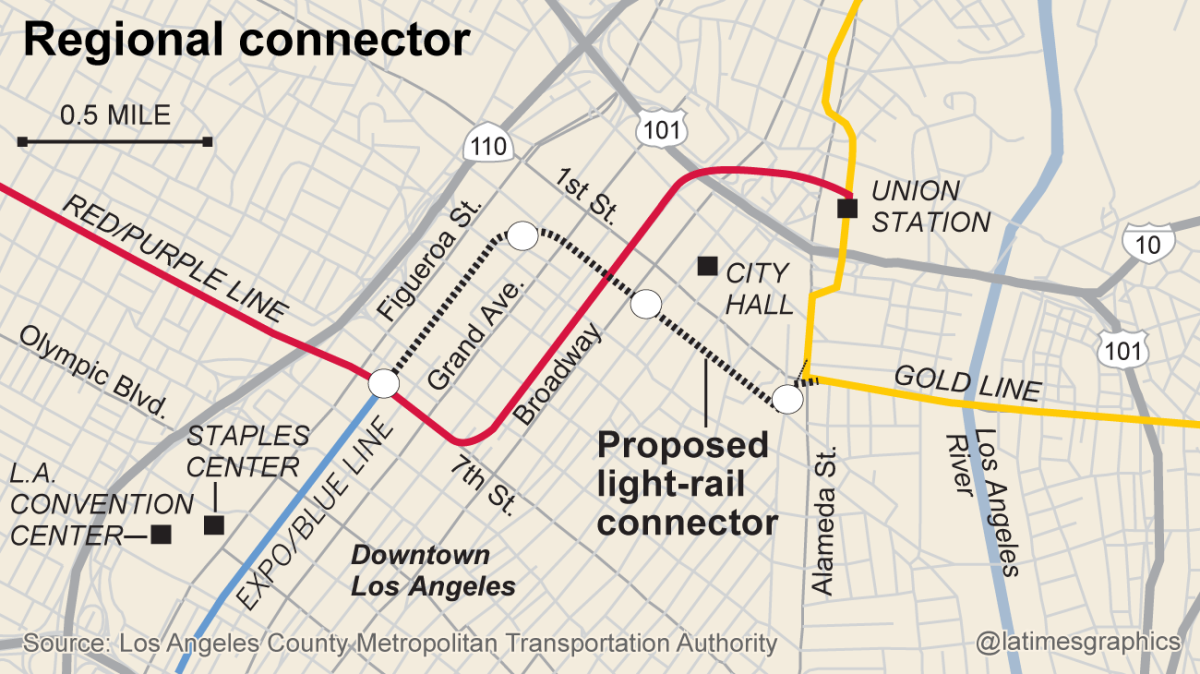

A 1,000-ton German boring machine known as “Angeli” is churning eastward beneath downtown, digging twin tunnels aimed at addressing one of the Metro system’s most obvious flaws: Any light-rail trip that passes through downtown requires at least two transfers.

The $1.75-billion tunneling project, known as the Regional Connector, will reorganize the Blue, Expo and Gold lines into two lines that will connect Long Beach to Azusa and East Los Angeles to Santa Monica.

Currently, riders have to board the Red or Purple Line subways to bridge the gap between Union Station and a transit hub on 7th Street on the western edge of the central city. The project will provide a one-seat ride for passengers whose trips cross through downtown.

The Regional Connector should smooth the transit experience for crowds of visitors watching beach volleyball games in Santa Monica, water sports in Long Beach or the 26 Olympic and Paralympic events in downtown, officials said.

Though Regional Connector promises seamless travel, its construction has been anything but. Officials have grappled with schedule and budget woes as costs for utility line relocation soared. The opening date has shifted later, to 2021, and the budget has risen 28% above original estimates.

Mid-2020s: A train to the airport

The next light-rail line scheduled to open in Los Angeles County will run south from the Expo Line through Leimert Park, Inglewood and El Segundo. The 8.5-mile route, known as the Crenshaw Line, is slated to open in 2019.

But Angelenos will have to wait five additional years for the most anticipated part of the line: A rail connection to Los Angeles International Airport.

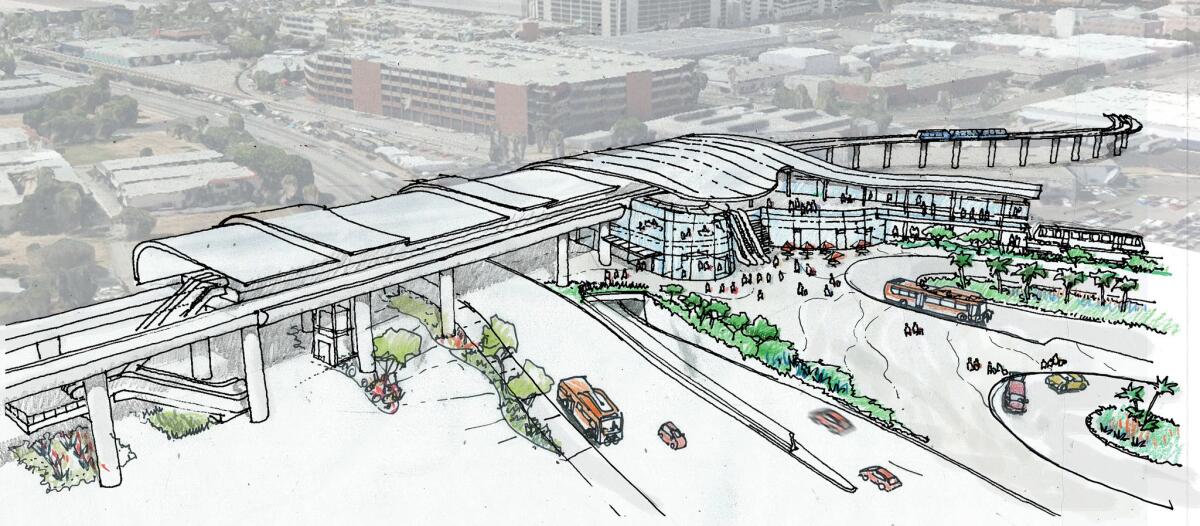

A new station at 96th Street and Aviation Boulevard is being designed to address one of Southern California's most infamous planning problems.

By 2025 or so, travelers and airport workers will be able to step off the Crenshaw Line a mile and a half east of LAX and board a smaller, automated train that will shuttle between a consolidated car-rental facility, a ground transportation hub and the terminal area.

The aerial train, which transportation officials call an “automated people mover,” is expected to cost about $1.5 billion and will be funded by the city’s airport department.

The Crenshaw Line is funded through Measure R, a half-cent sales tax increase for transportation projects that county voters approved in 2008.

Mid-2020s: A subway to West L.A.

The Purple Line subway will shave the trip from the Westside to downtown Los Angeles to half an hour, and is key to the region’s Olympics bid.

Transportation officials had vowed to finish the line 11 years early — just six weeks before the 2024 Olympics. (“If it doesn’t happen before 2024, you can fire me,” Metro CEO Phil Washington said earlier this year.)

The 2028 Olympics will provide four years of breathing room for an agency that often struggles to open major projects on time.

Metro will open the Purple Line to the Westside in three phases: from the current terminus in Koreatown to the Miracle Mile by 2023; to Century City in 2025; and the final phase, to West L.A., sometime before 2028. The project is currently ahead of schedule, officials say.

Transportation officials are now concerned about

A

Still, officials are optimistic. Metro has secured three packages of grants and low-interest loans for transit since the Republicans regained control of the Senate in 2010:: $830 million for the Regional Connector, and a combined $3.7 billion for the first two phases of the Purple Line.

The transportation legacy of the Olympics

For months before the 1984 Games, officials warned commuters of "Black Friday"— a day with more than a dozen Olympic events spread across the region.

The traffic nightmare never materialized. But the same scare-tactic strategies formed the playbook for another potential traffic apocalypse a generation later: Carmageddon.

The 1984 Olympics also provided the ultimate test for a suite of new transportation technologies that The Times described as a “panoply of Space Age electronic gadgets.”

Those tools — including sensors embedded in the street, meters on freeway ramps and video cameras to capture traffic flow — later became ubiquitous.

City engineers also connected a handful of intersections near the Coliseum to each other by remote control, theorizing that traffic signals that could talk to each other could move traffic more efficiently.

After the Olympics ended, the traffic light synchronization project plodded on. Whenever money became available, engineers connected more signals to a central computer system housed beneath City Hall in a space that was formerly a nuclear bunker.

The last of the city’s 4,398 traffic signals was synchronized in 2013, 29 years after the Olympics.

ALSO

Usain Bolt has a clear image of how his final race will play out

'We expect to compete for a medal': Former King Tony Granato to coach 2018 Olympic men's hockey team

Poll: L.A. residents want the Olympics, even if they must wait until 2028

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.