Mentally ill inmates are swamping the state’s prisons and jails. Here’s one man’s story

Reginald Murray sat next to his mother for the first time in more than a year, under the alternately bored and watchful eyes of the guards in the visitors’ room at Atascadero State Hospital.

He teased his mother about her weight; she teased her son about the scruffy beard he had grown.

They weren’t allowed to hug after the initial greeting. Instead, Murray kept reaching over to touch his mother’s arm. She made a show of being annoyed, but they were both smiling.

The state mental hospital on California’s Central Coast wasn’t where Murray wanted to spend the day after his 27th birthday. But it was better than where he had been a month earlier — in a solitary unit in the state prison in Lancaster.

Everything that could go wrong did go wrong.

— Attorney Mieke ter Poorten on the circumstances that led to her mentally ill client, Reginald Murray, being sent to prison

Over the last two years, Los Angeles County officials have announced a new focus on diverting people who are mentally ill from jail and prison. In July 2014, Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey told county supervisors that the jailing of mentally ill defendants was “a moral question.”

“The use of the jail as a mental health ward is inefficient, ineffective and in many cases it is inhumane,” she said.

But it is also growing.

See the most-read stories in Local News this hour >>

Even as officials have announced plans to address the issue, the number of mentally ill inmates has grown in both county jails and state prisons, although overall inmate populations have shrunk. In L.A. County jails, the average population of mentally ill inmates in 2013 was 3,081. As of mid-May it was 4,139, a 34% increase.

In the state prison system, the mentally ill inmate population was 32,525 in April 2013, making up 24.5% of the overall population. As of February, according to a recently released monitoring report, the overall population had fallen by 5,230 while the mental health population had grown by 4,275, and made up 29% of the total population.

A spokesman for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation gave an even higher percentage — 37% — but noted that most of the patients have lower-level conditions that do not require inpatient or enhanced outpatient treatment.

Murray, who has been diagnosed at different points in time with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and has spent the last three years in jail and prison, is part of that surge. Those close to his case see it as an illustration of the pitfalls in the intersection between the mental health and criminal justice systems.

“Everything that could go wrong did go wrong,” said his attorney, Mieke ter Poorten.

*****

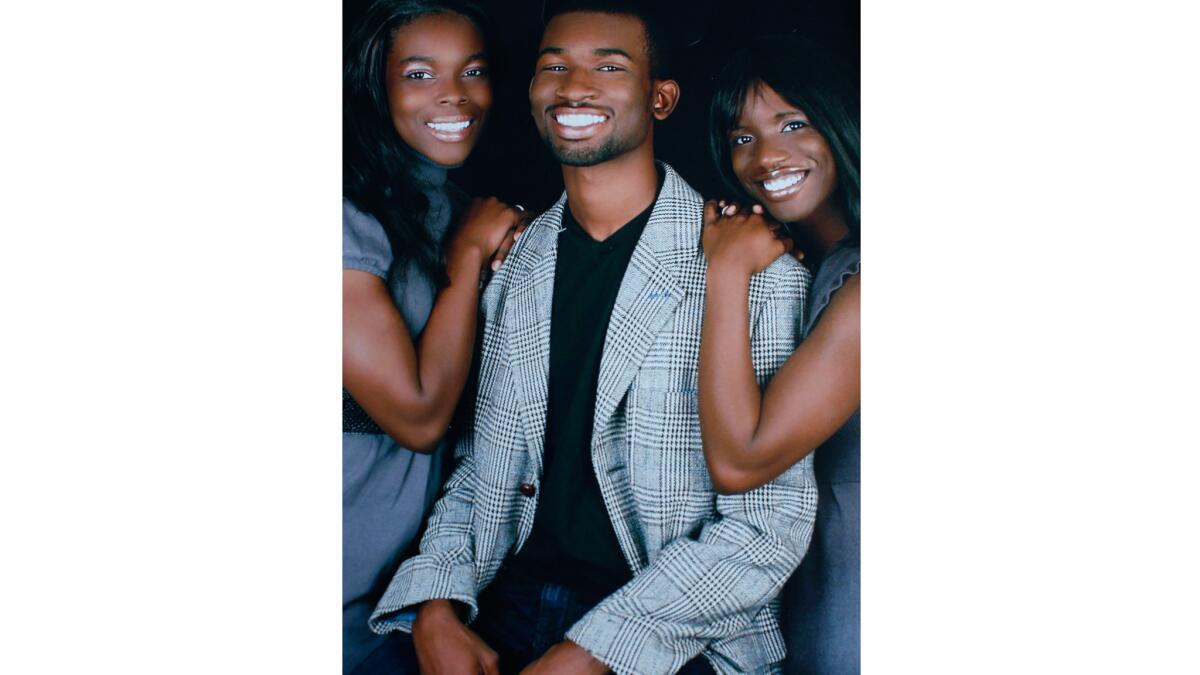

Murray’s beginnings did not seem auspicious. He was raised in Watts, and his father had been in prison since Murray was a baby. But his mother, Kookie Williams, pushed her children to be successful. Murray’s older sister grew up to be a teacher, his younger sister a corrections officer. Williams got a master’s degree in social work and counsels veterans at Los Angeles Trade Technical College.

Murray also seemed on track to do well. He showed an early aptitude for math and computers, and as a kid he earned spending money by fixing computers for people in the neighborhood. He decided he would become a computer engineer.

Murray and his sister KyOnta — the one who grew up to become a prison guard — agreed on one thing about their futures. “My brother promised me and I made a promise to him that we would never end up where our father was, no matter what,” KyOnta said.

His senior year of high school, Murray won a scholarship and decided to enroll at the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, a historically black college in a town where he had relatives.

But shortly after his high school graduation, Murray was driving with a friend, hit a pothole, lost control and ran into a pole. The accident left Murray with a fractured skull and his friend paralyzed.

Murray sank into depression. He had trouble concentrating and came home after one semester in Arkansas. He went back to work at the computer lab at his old high school and took some community college classes, but friends and family said he seemed to be drifting.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

In 2010, the family suffered another blow: Williams’ brother, who had been a father figure to her children, died suddenly of an asthma attack.

Over the next couple of years, Murray’s depression turned more ominous. He was hearing voices. He told his mother that crows were following him.

In March of 2013, he was taken to a hospital on a short-term, involuntary psychiatric hold after he called Kaiser Permanente and said he was thinking about suicide.

“I’m thinking of driving myself into something, but I don’t think I can kill myself that way,” he told the operator, according to a log of the call. “I would shoot myself, but no one else.”

Upon his discharge he was given a prescription for medication that he never filled.

*****

The situation came to a head on June 1, 2013.

Murray had gone to live with his aunt and cousins in Camarillo after his uncle’s death. His aunt, alarmed by his increasingly erratic behavior, told his mother to come get him.

The family called 911, hoping to have him taken in on another psychiatric hold, but Ventura County sheriff’s deputies decided he didn’t meet the criteria of being a danger to himself or others. Instead, Murray drove back to his mother’s house in Los Angeles.

KyOnta, who met him there, said she called the police after he made what she believed to be a suicide threat.

By the time police arrived, she said, she and her brother were struggling at the front door as she tried to stop him from leaving. He slammed her into the front window, breaking the glass. She remembered him calling, “I’m sorry!” before he ran out the door.

Again, the police did not stop him.

At 1:50 a.m. the next day, Murray crashed his car going more than 100 mph on the 110 Freeway.

In the next few minutes, witnesses said, Murray attacked a motorcyclist who had slowed down at the scene, punching the man repeatedly and trying unsuccessfully to ride off on his bike. He tried to pull another driver out of a pickup truck. After struggling with police, he was subdued and loaded into an ambulance.

Williams said she believes that if officers had taken her son in for psychiatric evaluation the day before his arrest, “I don’t think we would have been going through all this.”

“They would probably have reevaluated him and he would have been put on meds,” she said.

In an interview, Murray said he blacked out while driving. He remembered crashing, then being hit by a car and by the motorcycle. He said the motorcycle rider then offered the bike to him.

A report by a California Highway Patrol officer who rode with him in the ambulance said he stared at the ceiling blankly, unresponsive to questions until he suddenly said, “I told you I died at 1:20 tonight.”

*****

Murray was charged with carjacking and attempted carjacking and faced a potential nine-year prison sentence. A public defender had Murray evaluated by a psychiatrist but did not mount a defense based on his mental health.

With the case moving toward trial, Williams hired Ter Poorten, a private attorney. After another psychiatric examination found that Murray had serious mental health issues, she tried to negotiate a deal that would allow him to serve his time in a locked mental health facility instead of prison. The district attorney’s office did not agree.

Neither of Murray’s defense attorneys formally declared a doubt as to his mental competency, which would have stopped the criminal proceedings and triggered a special hearing. His public defender did not respond to a request for comment; Ter Poorten said she was inexperienced with mental health cases at the time.

In April of 2014, Murray pleaded no contest to attempted carjacking and was sentenced to three years in state prison. At the plea hearing, Judge Craig E. Veals raised Murray’s mental health issues and asked Ter Poorten whether she was sure they wanted to take the deal. Ter Poorten replied that going to trial would “risk a greater sentence.”

“After consulting with him and his mother, we are very regretfully and with tremendous anguish accepting what we are doing today,” she said.

Prosecutor Garrett Worchell told the judge that the charges were both “serious and violent felonies” and the fact that one was being dismissed “may be a significant advantage” to the defendant.

Williams said that while her son was in county jail awaiting trial, he had been housed in the psychiatric unit and was taking medication that seemed to help his mental state.

“I saw him coming back to who he was,” she said. “I could see him, the son I knew.”

But once in prison, she said, he was no longer being medicated. His letters became increasingly incoherent. Convinced that prison staff were poisoning his food, he refused to eat and lost 40 pounds.

In September, with a few months left in his sentence, Murray was charged with making criminal threats against a prison psychologist. The psychologist reported that while she was interviewing him at the door of his cell, he made “an indistinguishable statement starting with ‘If I don’t get’ and ending with ‘28, I will kill you and any other [corrections officers]!’”

When the psychologist asked if he was threatening her, she said, he responded, “Freedom of speech,” then called her insulting names.

In an interview, Murray denied threatening the clinician.

Under a legal settlement with prisoners, California prison officials must assess whether mental health issues played a role in inmates’ behavior before deciding on discipline.

The clinician who evaluated Murray under that requirement wrote that he “clearly indicated that the incident was not related to his mental health” and said his mental condition should not be considered as a factor. Murray was sent to solitary housing and the case was referred to the district attorney’s office.

Ricardo Santiago, a spokesman with the district attorney’s office, said the office considered Murray’s mental health when evaluating the charge, but “the facts and other circumstances in this case supported the filing of a felony.” He declined to comment further.

Ter Poorten declared a doubt as to Murray’s mental competency, putting the proceedings on hold. After being evaluated by a psychiatrist at the Los Angeles mental health court, he was found incompetent to stand trial and sent to Atascadero State Hospital for treatment.

*****

Advocates often blame the swell in mentally ill inmates on the contraction of the mental health system.

In California, the number of acute psychiatric beds available in hospitals statewide decreased by 2,700 — or nearly 30% — from 1995 to 2013, according to the California Hospital Assn., while the state’s population grew by 20%. The vast majority of state hospital beds are now reserved for people like Murray, who came in through the criminal justice system.

Williams said she saw her son becoming himself again in the hospital. His paranoia subsided and he resumed eating.

Murray said the food was better at the hospital than in prison. He liked being able to get calls from family and friends. The prospect of being put in restraints for violating hospital rules made him anxious, he said, but he was less worried about being roughed up by the guards there.

But as he sat next to his mother in the hospital’s visiting room, Murray said the help was too late: “To me, being in a mental institute now — I’m thinking if they would have sent me here in the beginning, I wouldn’t have to be here in the end.”

Twitter: @sewella

READ MORE

A sane approach to dealing with mentally ill death row inmates

Report on increase in mental competency cases leaves many unanswered questions

Expedite executions to keep California’s death row inmates from going insane

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.