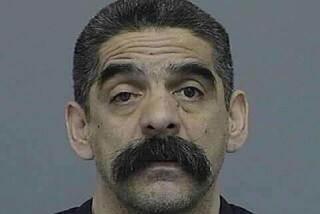

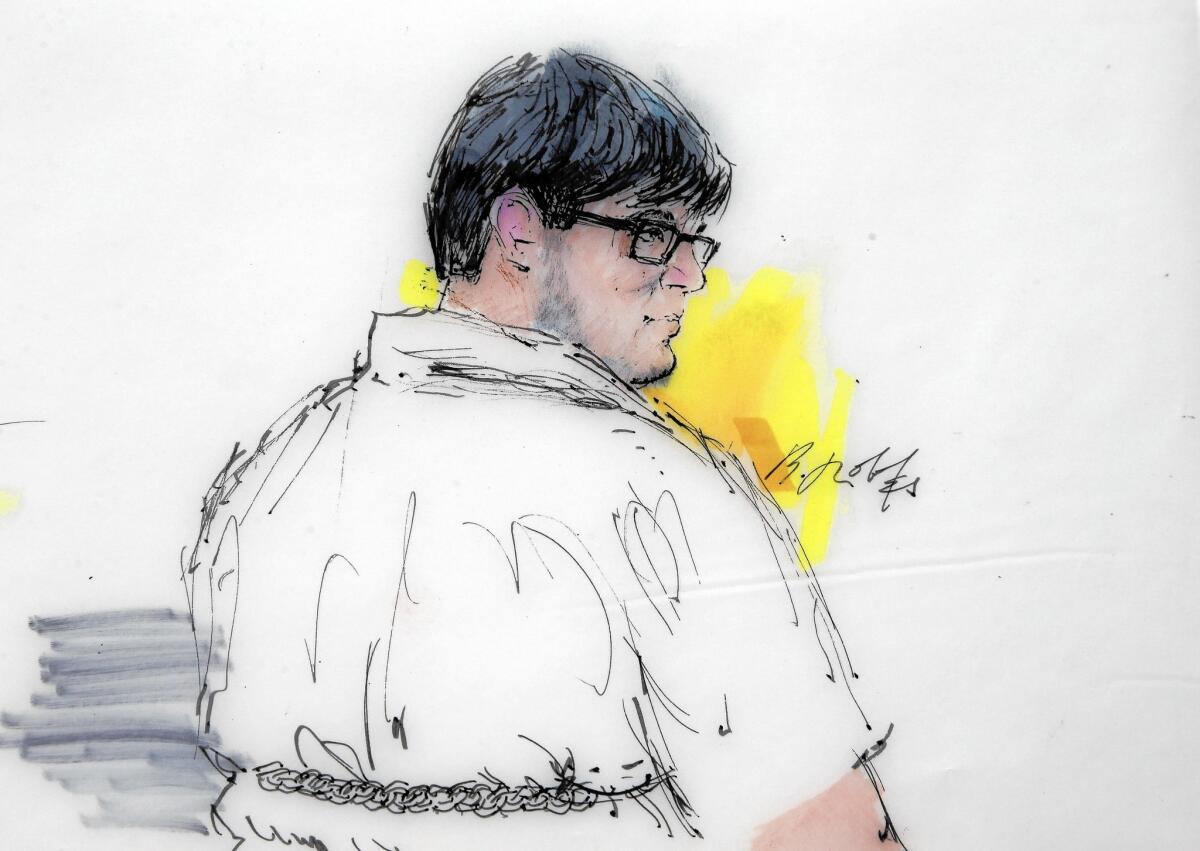

Goofy, friendly guy, or aspiring terrorist: Clashing portrayals of Enrique Marquez, friend of San Bernardino shooter

To the people around him, Enrique Marquez Jr. seemed like a straightforward guy with a silly streak and a shaky laugh. He was the suggestible type — always eager to fit in.

The 24-year-old spent his free time posting cartoons on Facebook and tinkering with old cars. He still shared a room with his brother and took up biking to shed some pounds in hopes of enlisting in the Navy.

But that simple image shattered last week when federal prosecutors portrayed him as a starkly different character:

A methodical and malicious man who purchased the military-style rifles his former neighbor used to massacre 14 people in San Bernardino.

A wannabe terrorist who immersed himself in radical Islamic teachings.

A conspirator who hatched a plan to blow up Riverside City College students with pipe bombs and sit in the hills above the 91 Freeway, shooting at cars during rush hour.

For Marquez’s former boss, Jerry Morgan, it’s all hard to believe — hard to reconcile the details laid out in federal court with the kid who checked IDs at Morgan’s Tavern a couple of times a month during rock shows. Marquez would sometimes come in when he wasn’t working and settle into a spot at the U-shaped bar, nursing a pint of beer and making conversation.

Marquez was the type of guy who coordinated rides for people who had had a little too much to drink and made sure women had a seat at the bar. He wasn’t tough or violent, Morgan said. In about four years of knowing Marquez, Morgan never heard him say anything suspicious.

“You just don’t ever know someone,” Morgan said. “He would have been the last person I would have suspected of doing this…. If this incident hadn’t happened, he’d probably be here saying, ‘Hey, you gonna buy me a beer?’”

Morgan said he believes Marquez was manipulated and molded by Syed Rizwan Farook, who along with his wife, Tashfeen Malik, carried out the Dec. 2 attack in San Bernardino.

Marquez is impressionable, Morgan said, and perhaps fell into something he didn’t know how to escape.

“He couldn’t fight his way out of a wet paper bag,” Morgan said.

Marquez, who also worked as a security guard at Wal-Mart, met Farook soon after moving to Riverside from El Monte in the mid 2000s. His family settled into a stucco tract home on Tomlinson Avenue, next door to Farook.

Although Farook was four years older, the boys shared a love of working on cars, and before long Farook opened up about his religion. Marquez converted to Islam in 2007. By 2011 he was spending almost all of his time at Farook’s house studying radical ideology, according to a complaint charging him with providing support to terrorists.

That same year, the neighbors began concocting a twisted plan.

The duo agreed that Farook’s appearance would draw unwanted scrutiny, so Marquez purchased smokeless powder for making explosives and two rifles, the complaint said. They planned to target the library or cafeteria at Riverside City College and throw pipe bombs from an elevated position on the second floor.

Asked recently by FBI agents what portion of the 91 Freeway they planned to target, Marquez pointed on a map to an area isolated from any exits. They’d wait for rush hour, Marquez told agents, and then start shooting.

Marquez admitted that they planned the attacks, according to the complaint, “to maximize the number of casualties.”

He told agents that to prepare, he studied online tutorials about firearm tactics and how to maintain a clear shooting angle while rounding a corner. He visited gun ranges, sharpening his shot, and studied a magazine published by Al Qaeda to learn how to make an explosive device.

He managed to keep it all hidden.

His friends knew him as a goofy guy who played the ukulele, cracked up at his own jokes and had a melancholic streak. One friend, who asked not to be named to avoid media attention, said that when her boyfriend cheated on her, Marquez rushed to console her. Another time, she said, he walked two miles to the veterinarian carrying her friend’s sick dog.

“I hate reading about him or hearing about him,” she said. “I just don’t believe it. I can’t.”

People who knew Marquez did find one thing about him a bit unusual: his marriage.

One friend said Marquez confided in her, saying that he and his wife, Mariya Chernykh, were “not clicking.”

But it seems the married couple hardly knew one another.

The marriage, Marquez told federal agents, was a sham — a business transaction, according to the complaint. He had agreed to marry Chernykh, a Russian émigré and the sister of Farook’s brother’s wife, at the Islamic Society of Corona-Norco in 2014 to help her get immigration papers. In exchange, he told authorities, she paid him $200 a month.

Marquez had recently messaged Chernykh — who lives with her boyfriend in Ontario — saying he was nervous about an upcoming meeting with immigration officials, according to an affidavit attached to the criminal complaint.

“Omg!!” she wrote back, “Enrique I’m the one freaking out here!!! Relax I’ll see u Monday and we’ll talk…[i]f they decline me its my problem not yours.”

Nick Rodriguez, who met Marquez at Morgan’s Tavern, said Marquez admitted that his marriage was a charade, saying that his wife wouldn’t kiss him and that he was paid to marry her.

There were other warnings too. During one unusual conversation, Marquez had mentioned the existence of sleeper cells.

“You guys have no idea how many people are out there,” Rodriguez recalled him saying. “They’re waiting. It’s going to be big when they do.”

But Rodriguez brushed the comments off as harmless bluster — just as he did the time that Marquez spoke about guns.

“I looked at him like, ‘Dude, you can’t even use a slingshot,’” he said. “‘What are you talking about guns?’”

Marquez hid parts of himself even from his family.

His mother, Armida Chacon, sobbed outside her Riverside home on a recent morning. None of the scary things she was hearing about her son made any sense. He’d always been her “right-hand” man, she said, eager around the house. A normal twentysomething who spent time with friends and went to parties.

“My son is a good person,” she said. “I don’t know how this happened…. My world is upside-down.”

It all caved in the day after the shooting, when Marquez checked himself into Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. He told the hospital staff that he was very upset and had pounded nine beers, according to the affidavit. He rambled about the San Bernardino shooting.

“I’m involved,” he told the medical staff.

Two weeks later, federal authorities charged him with buying the rifles used in the San Bernardino attack — the deadliest terrorist attack in the U.S. since Sept.11, 2001.

But up close, Marquez’s façade had started to crack even before his arrest.

One night in November, the complaint said, he opened his Facebook and wrote a note saying that he didn’t think anyone really knew him and that he lived multiple lives.

“My life turned ridiculous,” he wrote. “Involved in terrorist plots, drugs, antisocial behavior, marriage, might go to prison for fraud, etc.”

He couldn’t help but wonder, he wrote, when it would all collapse.

Times staff writers Matt Hamilton and Paloma Esquivel contributed to this report.

MORE ON SAN BERNARDINO

Family members remove items from home of San Bernardino shooters

Increased security for Rose Parade and Rose Bowl after San Bernardino attack

Criminal complaint illuminates San Bernardino gunman’s ties to Islamic militarism

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.