Fear of ‘collateral’ arrests hangs over ICE sweeps

A rooster’s crow filled the quiet Compton street as two immigration agents knocked on the door of the baby-blue-colored house. They were there to arrest a woman with convictions for theft.

Instead, they encountered Sonia, a 52-year-old mother who makes a living selling pupusas from the front porch.

As the fugitive operations team searched a separate back house, the street vendor told one of the agents that she was from El Salvador. She did not volunteer that, like their target, she was not in the country legally.

In the Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration, people like Sonia are in increasing danger of becoming collateral damage. ICE agents are out in force in immigrant neighborhoods across the country looking for specific offenders here illegally whom the government wants to arrest and deport. But they are often coming across many more people here illegally who are not wanted by the agency but still face the danger of being picked up.

Arrests of noncriminals by agents in the L.A. field office rose from 4% in 2016 to 12% in 2017. This has increased anxiety around the L.A. area since President Trump took office. To Trump’s supporters, there is nothing wrong with picking up those in the country illegally if agents come across them.

But critics have cited such arrests as a clear sign of the administration’s overexuberance to deport immigrants and make their lives miserable, whether they have criminal records or not. ICE officials blame “sanctuary state” laws for so-called collateral arrests, saying a lack of cooperation with California law enforcement has made it more difficult for them to find wanted people and forces them into neighborhoods.

And so, on this Sunday morning — whether she knew it or not — Sonia the pupusa peddler found herself on a razor’s edge.

In the back of the house, a woman told ICE agents that their target had been kicked out about half a year ago for not paying rent. As for Sonia, the agents never asked about her legal status. An agent thanked her and said they would not bother her again.

About 10 minutes after arriving, the ICE team left to continue with their part on the first day of an operation the agency hoped would lead to 500 arrests across Southern California.

“They were so nice that I didn’t get scared,” Sonia said later, though she wondered whether the presence of a reporter might have made the scene play out differently.

By the end of the operation on Tuesday, the Los Angeles field office had made 162 arrests, including a Mexican national convicted of rape and a citizen of El Salvador convicted of voluntary manslaughter. Of the 157 men and five women arrested, most of them — 129 — are Mexican nationals, according to ICE.

Almost 90% of the people arrested had criminal convictions, according to ICE.

In the last operation earlier this year, agents made 212 arrests over a four-day period.

“These operations can show that what ICE does is protect the community,” said David Marin, director of Enforcement and Removal Operations for ICE in Los Angeles.

Marin said that there are so many potential targets in the region with criminal records that the agency can focus on them.

Of Sonia, the street vendor, Marin said:

“Some people would say, OK our encounter with her — why didn’t you arrest her? Well our officers had no reason to ask her any questions to establish probable cause,” he said. “She wasn’t the person we were looking for, and she was being very cooperative with us.”

That discretion, however, has not always favored immigrants with no records.

In the first quarter of fiscal 2018, San Diego’s ICE office arrested more people with no criminal records than anywhere else in the U.S. That field office, which also covers Imperial County, was the only one in the country where the majority of arrests — about 72% — were of “noncriminals,” according to the agency. (At the time, about 16% of the people arrested by ICE officers in L.A. did not have criminal records.)

Marin cited the Atlanta and Chicago offices as jurisdictions that are “arresting a lot of non-criminals” compared with the L.A. office.

“I only have so many officers. I’m going to focus on those criminals because I know those are an immediate threat,” he said. “Some say they’re criminal because they crossed the border illegally. But just an illegal alien. Yeah, I can arrest them, but I don’t have the resources to.”

ICE’s Los Angeles office covers a vast region that stretches from San Luis Obispo to San Clemente and from the coast to the Nevada border. At least one team is active each day, making arrests. Although 2017 arrests by agents in the L.A. field office were up 10% from the previous year, rising to 8,419, it was a far cry from the over 25,000 arrests in 2013 and more than 18,000 in 2014, according to ICE data.

During the most recent three-day operation, 12 teams made arrests in L.A., Orange, San Bernardino, Riverside, Santa Barbara and Ventura counties.

Latinos make up an estimated 50% of the L.A. field office, Marin said. Of the seven agents gathered for a 5 a.m. briefing in the parking lot of a Compton shopping mall, five were Latino. Many agents spoke fluent Spanish, which came in handy as the team worked their way through a list of six targets.

Half of them were legal permanent residents whose status was jeopardized because of criminal convictions.

First on the list was the woman they thought lived at the Compton address. She had been picked up for vehicle theft and two different cases of petty thefts. The 26-year-old had applied for DACA, but was denied because she never provided evidence that she qualified for the program.

An ICE agent said that the woman had been taken into custody, but that the law enforcement agency that had arrested her did not not honor an immigration hold on her.

“Wherever she went into custody, they didn’t honor our hold due to the sanctuary policy,” he said. “So now she’s out on the street.”

After leaving the first address empty-handed, the ICE agents moved on to the next target, Adriana Espejel, who came with her parents from Mexico City when she was 5. The 26-year-old, who has had a green card since 2010, was convicted in May of possession of a controlled substance for sale.

They had already done surveillance on the home where she lived with her boyfriend in an industrial area of Compton. Shortly before 6:30 a.m., agents knocked on the carport in front of the house, which sat between factories. In the front yard was a playground set, with a red slide and swings, as well as a stroller.

A dog barked relentlessly as the agents shouted “Police,” until they were able to make contact with Juan Sanchez, Espejel’s boyfriend.

Believing the agents to be police — they wore vests that read “police” with a small badge that read “ICE” — Sanchez let them in. Espejel was sleeping on the couch with Sanchez’s 3-year-old son. The agents walked her outside and handcuffed her.

“Honestly, I’m real lost,” Espejel said, as one of the agents walked her to a black SUV with tinted windows.

“You have a green card, correct?” the agent asked her. “Any time you’re in trouble or convicted of a crime, that lets us know.”

An arrest causes one’s fingerprints to be logged electronically with the FBI and Department of Homeland Security, Marin said. When a lawful permanent resident is arrested for a removable crime, agents make a note to follow up on the person later.

But the ultimate decision on whether a person is removed from the country is determined by an immigration judge

Marin said it’s important for legal residents to try to become U.S citizens.

“If she would have become a U.S. citizen when she was eligible, we wouldn’t be here,” Marin said about Espejel. “We wouldn’t be knocking on your door if you were a United States citizen. But because she’s a lawful permanent resident, because she’s committed crimes that make her amenable to removal, she has to answer to it.”

Agents came up empty in Lynwood. They moved on to Huntington Park to search for Abel Martinez Guzman, another lawful permanent resident who had been convicted of cruelty to a child.

Rather than arrest him inside his home with his three children inside, the agents took him out front, where a geometric dome sat on the green grass of his front yard. He emptied his pockets of his wallet and a Dodgers lanyard that held his keys.

The agents left his wife with a card that listed his alien registration number, a unique nine-digit number given to anyone who applies for immigration benefits or who is in deportation proceedings. They gave her a phone number to call for information. With her arms crossed, Guzman’s wife watched as the agents placed her husband inside the black SUV.

Guzman quietly thanked the agents for not arresting him in front of his children.

The agents searched for another target, their fifth, also in Huntington Park.

A person inside the house where they thought the target might live told the agents that the man they were looking for moved out two weeks ago.

Throughout the day, agents complained about Senate Bill 54, a California “sanctuary state” law, as well as other policies they say have affected their operations. In 53 of the cases during the operation, ICE had filed detainers with local law enforcement officials, requesting that they be notified when a person in custody will be released, according to the agency.

One of the agents said that he felt that the negative opinion of the agency has recently intensified.

“Even the cops don’t like us anymore, because they’re listening to the news also. ‘Oh you guys are just separating families,’” said the agent, who did not want his name included. “It’s not like we like being seen like that. We don’t like it, but it’s positive that we’re out here, in my opinion. And we do this every day. We get tired of it, we get tired of the negative looks — but what are we going to do?”

The agent blamed media coverage.

“The media portrays us badly for the most part. But I know what we’re doing,” he said. “When the media comes out with us and sometimes they interview the detainee they’ll be like, he has five kids, he’s married, only wage earner … But what did he do?”

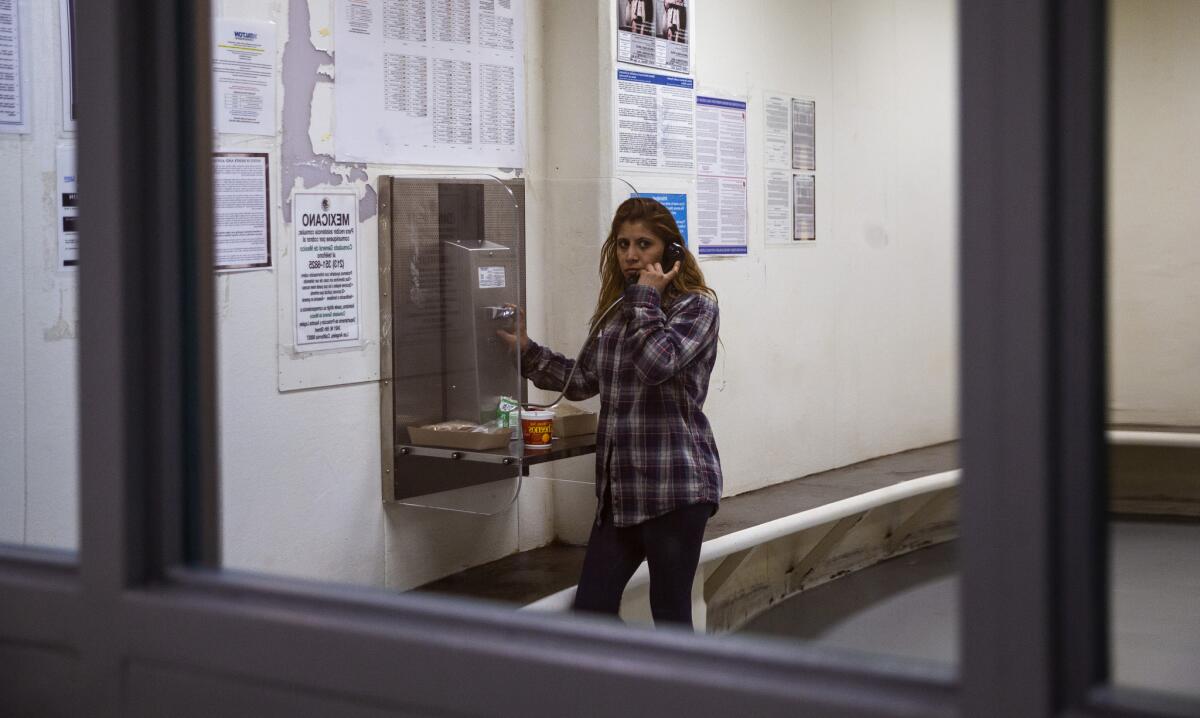

At the processing center, detainees were instructed to remove shoes and drawstrings from shorts as a safety precaution. Espejel got a medical check and her fingerprints were taken, before she sat down with an agent to answer questions.

Espejel is one of triplet sisters. One of her siblings has residency and the other is a citizen, she told a Times reporter. Espejel kept repeating that she is not here illegally and that her permanent residency has no expiration.

Through shaky breaths, Espejel shared her story about how her parents left Mexico to give their children a better life. Her father worked hard to get her and her siblings their residency, she said.

“I feel like I’m letting him down,” Espejel said. “I feel like it’s his biggest disappointment.”

When she was arrested in January 2017, she was living on the street, Espejel said. Soon, she got addicted to meth, but denied trying to sell large amounts.

Espejel was convicted in May and served eight days in jail before being released more than a month ago and put on probation, she said.

“I went in jail, served my time, I don’t see why immigration picked up on it after when I was already released,” said Espejel, her mascara smudging as tears streaked down her face. “Why am I here now, if I paid my time?”

Espejel’s boyfriend later said that she had changed, finding a job and helping him raise his son. He said he regretted opening the door.

“If I had known it was ICE, I wouldn’t have let them in.”

For more California news, follow @brittny_mejia

UPDATES:

11:30 a.m.: This article was updated with additional information from ICE.

This article was originally published at 7:30 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.