As more Latino kids speak only English, parents worry about chatting with grandma

Like many first-generation Mexican immigrants, Juan Rivera grew up in a home where the family communicated exclusively in Spanish.

So when he had his own children, it was important that his home be bilingual. He plastered the family’s Paramount home with sticky notes inscribed with words in Spanish and English of each household item.

But soon the children reverted to speaking just English, and the notes vanished.

The Rivera family’s experience mirrors a dramatic linguistic shift occurring in Latino communities across the country. More Latinos are growing up in households where only English is spoken.

A new Pew Research study released this week found that in 2014, an estimated 37% of Latinos ages 5 to 17 grew up in households where only English was spoken. That’s up from 30% in 2000.

Overall English proficiency is on the rise and a declining share of Latinos of all ages are speaking Spanish at home, the study found.

The findings reflect the significant decline in immigration from Latin America in recent years, which has reduced the number of first-generation families. It also shows that Latinos are repeating a well-traveled path of assimilation embraced by other immigrant groups such as Italians and Germans.

“The typical trend is that the first [generation] prefers to speak Spanish, the second generation is bilingual, and the third generation is generally monolingual,” said Jody Agius Vallejo, an associate professor of sociology at USC who studies immigrant integration.

Still, the movement runs counter to some of the fears critics often express about the huge amount of immigration — both legal and illegal — into the U.S. from Latin America in the last few decades. California voters in 1998 approved a ballot measure that killed most bilingual education programs in public schools in favor of English only amid fears immigrants would prefer to keep speaking Spanish.

The shift toward speaking only English comes with its own complications.

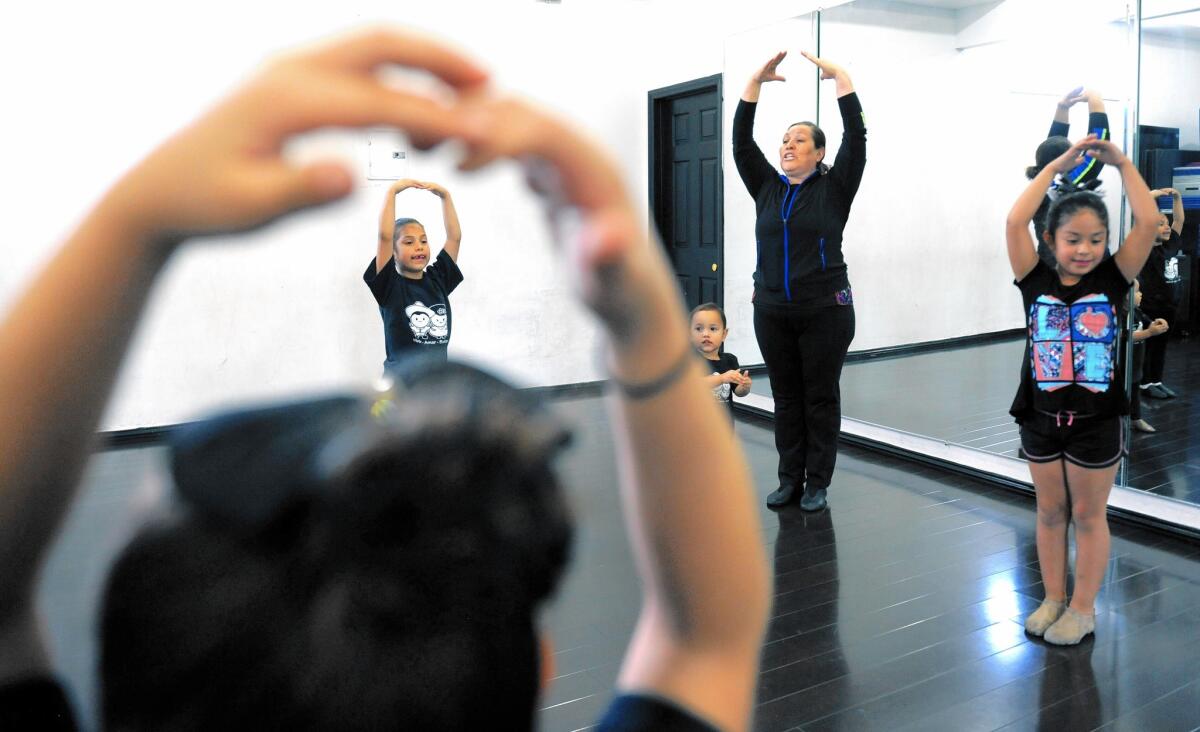

Outside a dance studio in the predominantly Latino immigrant town of Cudahy, mothers waited for their daughters to leave a folkloric dance class. Most of the children spoke English, but the instructor, Lourdes Perez, speaks almost entirely in Spanish.

As the mothers waited, they joked about speaking to their children in Spanish only when it’s time for punishment. But they also lamented the fraying line of communication between their children and their Spanish-speaking grandparents.

Maria del Rosario Peralta questions her own daughter about her reluctance to speak Spanish.

When she speaks to her daughter in Spanish, her daughter responds in English.

This summer, the family plans to visit the grandparents in Mexico. Peralta worries that her daughter will need an interpreter to communicate with her relatives.

“I tell her, ‘What’s going to happen when we go to visit your grandparents?’” Peralta said. “Vas a hablar o te vas a quedar muda?”

Translation: “Are you going to talk, or are you going to stay silent?”

Karen Rivera grew up speaking very little Spanish in the home, but her husband’s parents were born in Mexico and her mother-in-law doesn’t speak English. Whenever the couple visits her in-laws, the children practice the little Spanish they know on the car ride over.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

“Buenas tardes, como estás,” her daughters will repeat.

“They’re in the car saying it over and over to make sure they can pronounce it correctly,” Rivera said. “If the grandparents ask them a question, they try their best to answer it.”

In the last 14 years, English proficiency among Latinos has been largely fueled by Latino youths born in the United states.

Nearly half are under 18, and 88% speak only English at home or speak English very well, according to 2014 data from the U.S. Census Bureau. That’s up from 73% in 2000.

Among millennial Latinos — ages 18 to 33 — the share who speak only English at home or say they speak English very well rose from 59% to 76% during the same time, the data show.

“We often tend to think of immigrants being the main driver of the Hispanic population, but it’s actually U.S.-born Hispanics who are drivers of the Hispanic population,” said Mark Hugo Lopez, director of Hispanic research at the Pew Center.

The number of newly arrived immigrants from Latin America has been in decline for a decade.

Erika Aparicio, 24, of San Diego arrived in the U.S. on a visa when she was 6 and is fluent in both English and Spanish. Her mother and father are also fluent in both languages. But Aparicio prefers to speak to her parents in Spanish.

Aparicio makes a concerted effort to speak exclusively in Spanish to her 3-year-old U.S. born daughter, too.

“I’m not going to let the Spanish die with me,” she said. “I see the value in knowing two languages.”

At times her efforts have led to awkward moments in public. Recently while in line at the bank, Aparicio said she was talking with her daughter Ashley in Spanish when she noticed an older man staring. When Aparicio responded to a bank associate in English, the man seemed to be taken aback, she said.

“He was surprised,” she said and let out a laugh. “I don’t think he thought we knew English.”

These perceptions can turn ugly. In August, a videotaped confrontation went viral online of a woman interrupting a Los Angeles mother and son speaking Spanish to each other at an IHOP in Koreatown. In the video, the woman yells at the mother for speaking Spanish and demands that she speak English. The mother cries and yells back at the woman in English.

Spanish has long inspired contradictory impulses. On the one hand, many middle-class and affluent whites have enrolled their children in bilingual charter schools so they could learn Spanish, believing it could give them a leg up in the job market. But Spanish use has also provoked English-only initiatives across the country, Vallejo said.

It’s an old story in many ways, Lopez said, pointing to how Germans were criticized in the 19th and 20th century for supposedly failing to assimilate. In some states, such as Nebraska and Iowa, laws were enacted to ban German in public schools.

“The United States truly is a graveyard of languages,” Vallejo said.

In Maria Torres’ home, she and her husband speak only Spanish, although the two can also speak English. Because of their relatives in Mexico, Torres said, it is important for her daughters to be able to communicate in Spanish.

“If I hear them speak English in the house, I tell them no; only Spanish,” Torres said. “It’s important they have a grasp of both languages.”

For many families, language is more than just about speaking, Vallejo said.

“It is about your identity,” she said, “the relationships that you build and deepen with family and friends or through experiences like travel, and the memories that are derived from those relationships and experiences.”

ALSO

Prince, master of rock, soul, pop and funk, dies at 57

How are Pennsylvania’s GOP delegates selected? Most voters don’t have a clue

Days before her death, wrestling star Chyna posted a rambling YouTube video

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.