In Alhambra, demographic shift reaches the grocery store

Susan Moy, right, compares products with Ali Feng, left, at the new 99 Ranch grocery store that recently opened in Alhambra.

As classic diners and soda fountains gave way to double-decker strip malls packed with Chinese restaurants, Margie Myers, a resident of Alhambra for 64 years, didn't say much.

She weathered friends and neighbors moving away and endured the steady retreat of English from storefront signs.

But the change she couldn't accept came in June, when the Ralphs on Alhambra's Main Street closed and was replaced by 99 Ranch, an Asian supermarket.

"I know the city's changing," Myers said. "That's just inevitable. But does it have to change our supermarket?"

Few hallmarks of demographic change generate as much controversy as the death of the neighborhood grocery store.

This spring, Alhambra residents packed City Council meetings at the news that the Ralphs on Main Street was closing, though the city had no role in the renting of the space. Rumors flew of Chinese ownership driving up rental prices to kick Ralphs out, though the property owners are not Chinese and Ralphs decided not to renew an expiring lease.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

The debate over Ralphs contained all the fears and frictions found in any rapidly changing community. Longtime residents couldn't accept that demographic change had reached their grocery baskets. Immigrants and newcomers complained of xenophobia and racism in the opposition's protests.

Alhambra's conflict echoes in communities across the Southland. Latino grocery stores move into South Los Angeles and a mini-Wal-Mart battles for market share in Chinatown, said Min Zhou, a professor of sociology at UCLA.

"It's almost like all of the fear and anxiety over demographic change focuses on a grocery store," Zhou said.

Since Ralphs Store No. 199 closed in March, Myers has been driving three miles farther to Pavilions in South Pasadena for her groceries. It's a short journey that begins in one era of the city and takes her through another.

She backs her Chevy Tahoe out onto a quiet tree-lined street of ranch-style homes. Her father, an Army veteran and former professional baseball player, bought their house new in 1947 for $10,700, and the city identified it as a historic neighborhood in 2005. She's lived here all her life.

She heads north toward Valley Boulevard, home to one of the largest and most vibrant Chinese commercial centers in the Southland. But Myers prefers to remember it as Crawford's Corner, a family-owned shopping center with a grocery store, gift shop and a gazebo where you could hear Dixieland music play.

SIGN UP for the free Essential California daily newsletter >>

Farther north, past Main Street where she used to turn left to go to Ralphs, Myers points disapprovingly at a senior housing complex built by a Chinese developer that towers over the surrounding homes.

"We're being pushed out," she said.

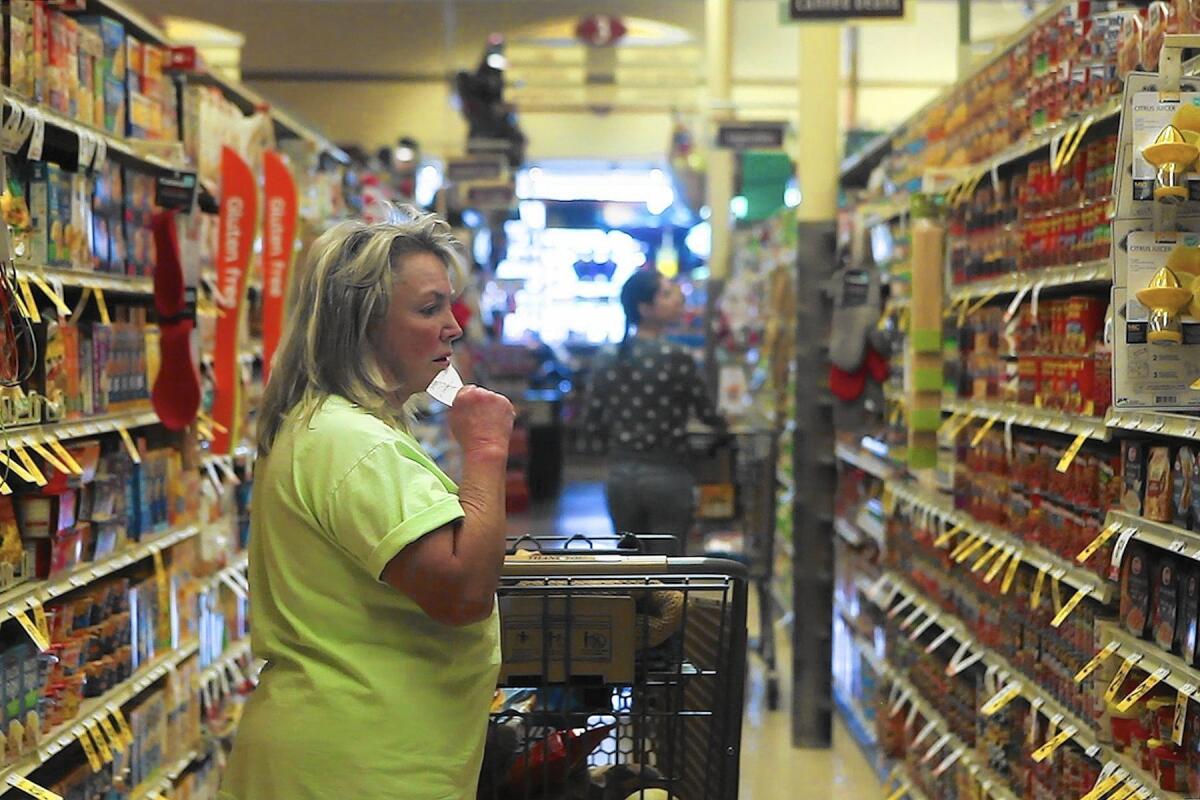

Myers pulls into the parking lot at Pavilions and consults a shopping list that includes potato chips, pickles, tomato paste, Bud Light, black olives, French bread and Vienna sausages. She's serving barbecue ribs, Caesar salad, potato salad and corn on the cob for dinner tonight.

She could buy those things at stores in Alhambra. But it's not about groceries, Myers said. It's about comfort — the familiar smell of the Pavilions, the American music on its soundtrack, the way the fish comes wrapped in plastic or displayed behind glass, and the language that the specials are announced in — English.

Having the right kind of supermarket in Alhambra isn't about convenience, Myers said. Her complaints about grocery shopping can snowball into grievances about bad driving, rude service at restaurants, cleanliness and eventually, what kind of community Alhambra should be and what it means to be American. Conversations about grocery stores, Myers said, always become conversations about belonging.

"All the businesses and the markets are becoming Asian," Myers said. "And I just don't fit in here anymore."

City leaders say they tried to negotiate to keep the Ralphs in place, but they can't tell landlords what tenants to contract with. They have even less control over the demographics of the city, which have changed dramatically during Myers' lifetime.

Alhambra's Asian population has increased from less than 3% in 1970 to 52% in 2013, according to recent census surveys. The white population of the city, which has dominated for most of the city's history, has fallen to about 11%. The Latino population has also declined slightly, to 35%.

The city's supermarkets rise and fall along with the city's demographics. Trader Joe's, Vons and another Ralphs have been among the traditional Western supermarkets that have closed over the last two decades. Super A, a multicultural grocery store serving many Latino customers, closed in 2013.

When change reaches the grocery store, people take notice, Councilman Stephen Sham said.

"I don't like change either, but it's coming," Sham said. "I hope that everyone keeps an open mind and that they're realistic."

99 Ranch markets first gained fame for packaging Asian groceries for Western shoppers. The company has two unofficial slogans, spokeswoman Teresa Leung said: "window to the East" for those with American tastes, and "home away from home" for immigrants.

The new Alhambra store is an experiment to see if both missions can be merged, Leung said.

On a recent weekday, a Beach Boys song played over the supermarket's speakers. A banner tacked over a refrigerator case of Chinese sausages encouraged shoppers to "Bring home a taste from the Far East today." Produce shelves built to look like rustic wooden vegetable carts held peaches and pears next to electric pink jackfruit. Humming freezer cases offered dozens of varieties of frozen dumplings, but also Hot Pockets, Totino's Pizza Rolls and Nestle Drumsticks.

The company, which has 37 locations across the U.S., knows it's seen as an immigrant supermarket, but the Alhambra store is an attempt to expand beyond that, Leung said. 99 Ranch wants to attract a younger generation of shoppers who appreciate authentic Asian goods but also consume familiar American products.

"99 Ranch can't stay doing the same things the same way we did 30 years ago," Leung said.

When the company opened its first location in Westminster in 1984, ethnic supermarkets like 99 Ranch functioned as economic toeholds for early immigrant communities, said Linda Trinh Vo, an Asian American studies professor at UC Irvine.

In the San Gabriel Valley, they anchored strip malls and attracted restaurants, barbers, butchers and clothing stores, creating jobs for immigrants including Jun Chen, 65.

Chen and his wife settled in Monterey Park about 30 years ago, a short walk from a Shun Fat Supermarket and a 99 Ranch grocery store. He worked as a cook in nearby Chinese restaurants, which relied on the supermarkets for produce. His wife, a seamstress, benefited from the steady flow of Asian immigrant foot traffic to the area.

Together they earned enough to send four children to college. They retired three years ago to a home in San Gabriel.

"America has been good for us," Chen said. "We've always had work. We've done well here."

On a recent weekday, they headed to the 99 Ranch where they've done most of their shopping and loaded a cart with discounted okra.

Here, price takes priority over presentation. A blast of mingled vegetable, seafood and pastry odors greets shoppers at the entrance thanks to the air conditioner above the door. Produce and packaged food are often displayed in the boxes they were shipped in, and at the back, murky water tanks and bloody beds of ice hold live and recently alive seafood. There's some English on the price tags, but few people in the store speak it.

Chen has tried American grocery stores, but he always ends up back at 99 Ranch. Even after three decades in the U.S., they still prefer to cook and eat Chinese food.

"Your eating habits are the last thing to change when you're trying to adapt to a new culture," said Zhou, the UCLA professor.

The same goes for longtime Alhambrans adapting to the city's new Asian identity. At the new hybrid 99 Ranch on a recent weekday, more than 80% of the shoppers were Chinese.

A white couple, Mike and Kathy, wandered into the store recently and began to explore. They examined the rotisserie chicken cartons under the heat lamp at the front and admired the bread selection at the bakery.

But despite the store's efforts to disguise itself as a Western grocery store, Mike described it as an exotic cultural experience.

They left without buying anything, then drove to Pavilions.

Twitter: @frankshong

ALSO:

Should L.A.'s new minimum wage apply to union workers? Depends on who you ask

Times Investigation: Nearly 9 in 10 students drop out of unaccredited law schools in California

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.