How gay men in Long Beach were targeted by police and mocked by The Times a century ago

Long Beach’s morality was in doubt.

So claimed the Los Angeles Times in numerous sensationalist 1914 stories about the arrests of 31 men allegedly tied to two private clubs in the city where gay men were said to cross dress and have sex with each other.

It was a racy scandal, the Times sneered, with details that were “unprintable” — and yet one that the newspaper could not get enough of.

Long Beach police, following the lead of undercover “vice specialists” W.H. Warren and B.C. Brown, arrested the men on so-called social vagrancy charges, collecting steep fines — $5,275 in all — or throwing in jail those who could not pay.

The newspaper's account of the "scandal" that enveloped the city offers a window into the virulently homophobic attitudes that prevailed a century ago, when gay sex was illegal and police pioneered the use of undercover stings to identify and prosecute gay people. The stories also underscore the role that The Times and other newspapers played in perpetuating the era's homophobia.

The Times printed the names of the arrested men and mocked its neighboring city over the discovery of underground gay social organizations — the 606 Club and 96 Club. At one point, the newspaper published a story with the dateline, “The Holy City of Long Beach.”

But amid the sarcasm and public calls for purity, the sweep had devastating effects. One of the arrested men, a prominent Long Beach banker and church officer, killed himself by swallowing cyanide near the beach. In a note to his sister, he said he was innocent but “crazed by reading the paper this morning” in which his name had been published. Long Beach officials temporarily banned the sale of toxic substances afterward, fearful that others might follow suit.

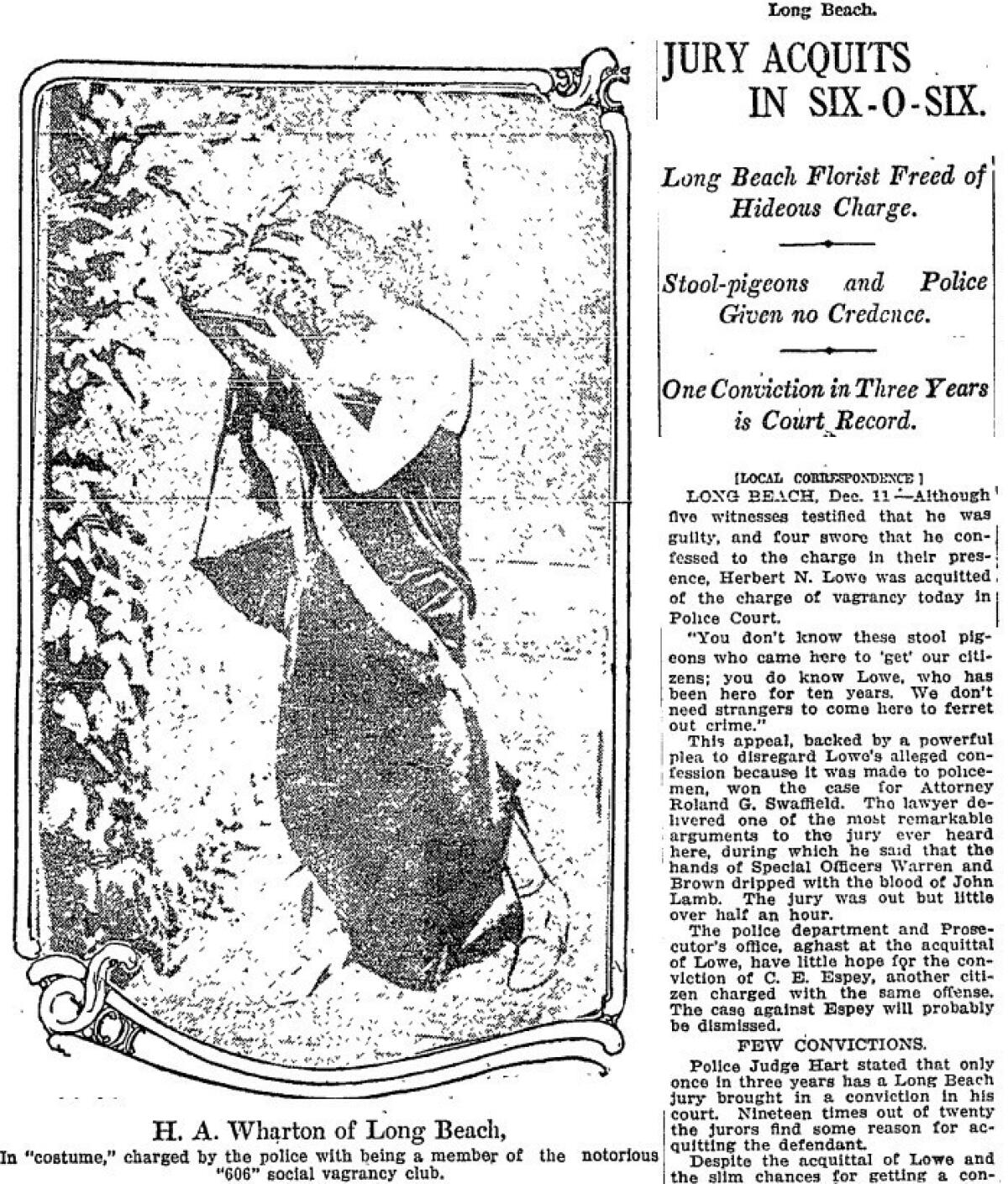

Only one of the men, florist Herbert N. Lowe, fought the charges. His trial, the Times reported, was the talk of the town, with large crowds fighting for seats in the courtroom.

“Doubting Thomases of Long Beach who refused to believe the existence of a certain class of vice in that city, heard in court yesterday the bald stories of the officers who put in jail thirty-one men on the charge of vagrancy,” the Times wrote of Lowe’s trial, adding that “It was a dramatic and hideous recital, and startled the populace.”

Officers Brown and Warren — reportedly attractive men who had no prior police training but were given badges in Long Beach and Los Angeles to rid the cities of vice – were the star witnesses, saying they got $10 for each captured “social vagrant.”

At one point, according to Times reports on the testimony, Brown rented a cottage from Lowe and arranged for other officers to watch from a peephole and window as he baited Lowe to flirt with him. One evening, Brown lay down on his bed, expecting Lowe to arrive. As officers spied on the room, Lowe tried to become intimate with Brown but was interrupted by a noise: Someone peeking into the room slipped loudly on gravel outside. Several officers then rushed in to arrest Lowe.

But in the end, the jury acquitted Lowe after his attorney said the undercover officers’ hands were “dripping with the blood” of the man who killed himself. The Times’ headline read: “Jury Acquits in Six-O-Six...Stool-pigeons and Police Given No Credence,” referring to the undercover officers.

Even in that era, the newspapers were criticized for publishing the names of arrestees, especially after the suicide, by some members of the public and by local officials embarrassed by the arrests.

But the newspapers defended themselves with self-righteous outrage. In November 1914, The Times published an editorial from The Sacramento Bee — titled “An Unprejudiced Observer: Publicity is Needed and Then More Publicity” — saying that despite criticism, newspapers should not suppress “news concerning this most horrible of all filthy crimes.”

Of the man’s death by cyanide, the editorial stated: “His suicide in itself was a confession.”

In 1915, several months after the sting operation, one of the Long Beach vice officers, Warren, and a married woman with whom he was infatuated were found dead in an apparent murder-suicide, The Times reported.

The newspaper described how Warren, who conducted the “now celebrated ‘social vagrant investigations,’” referred to himself as “the master of women.” He shot the victim when she refused his advances and then turned the gun on himself.

The article mentions that Warren made a good living from arresting so-called social vagrants, sometimes more than $100 a week. Attributed to Warren’s “activity,” the Times said, was the death of a New York City actor he “exposed with a success that resulted in the man’s desperate leap from a window with a trunk strap around his throat.”

Twitter: @haileybranson

MORE

See more of The Times' coverage of the Long Beach 'social vagrant' investigations

Undercover police stings targeting gay men endure, despite fierce criticism

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.