Highland Park nonprofit takes the homelessness problem into its own hands

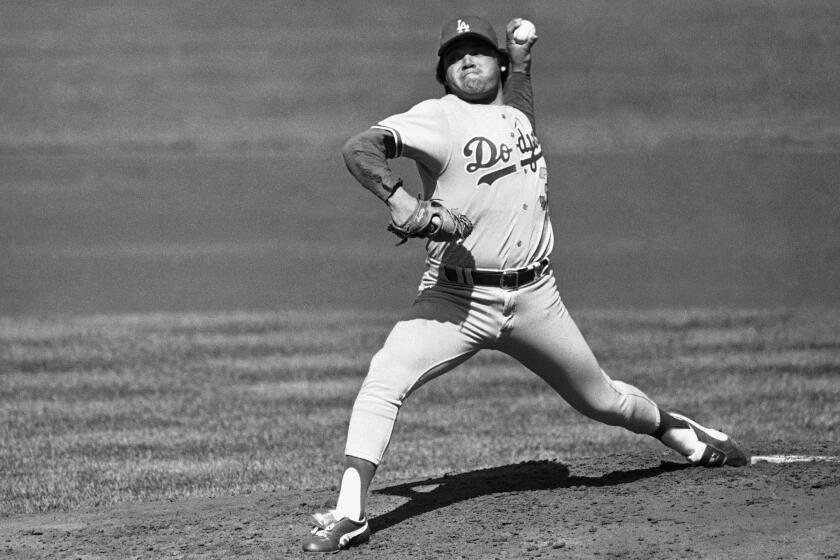

Dale Meyer, 58, settles in for a night at All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Highland Park. Meyer said he was born and raised in Highland Park and ended up homeless years ago after he was laid off from a print shop.

They began trickling into All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Highland Park in the early evening, unfurling sleeping bags along the pews, beneath an abstract crucifix wrought from twisted metal.

Elected leaders had been talking for months about the urgency to expand shelters before a much-anticipated El Niño brought wet and potentially deadly weather to the thousands of people sleeping in the streets.

But city action and funding stalled, so volunteers teamed with Pastor W. Clarke Prescott to open the all-volunteer overnight sanctuary last week to people like Cynthia Mitchell, who said she spent the previous night under a blanket on a friend’s porch.

“I’m so cold and shivery, and my feet feel like lead from walking so much,” Mitchell said. “I didn’t even have a pillow until this place.”

In September, seven Los Angeles City Council members, with the support of Mayor Eric Garcetti, pledged to declare a state of emergency on homelessness.

But the politicians later retreated, opting instead for what they say is a carefully coordinated planning process with the county that they hope will produce a comprehensive strategy early next year.

Members of a Highland Park nonprofit, Recycled Resources for the Homeless, took the homelessness crisis into their own hands, finding the church and recruiting volunteers for an experiment in grass-roots activism.

“People are in imminent danger,” said Rebecca Prine, director of Recycled Resources.

Homeless advocates said City Councilman Gil Cedillo, who represents part of Highland Park, had vacillated on supporting their project while pushing for anti-loitering signs, cleanups and parking restrictions to run homeless people out of local parks and off city streets.

“Nimbyism,” Prescott said.

Hours before the shelter opened, Councilmen Jose Huizar and Marqueece Harris-Dawson, co-chairs of the homelessness committee, announced they had filed a motion to set aside $13 million for homeless services, including funding for the Highland Park shelter. Cedillo, who pledged support for the motion, said he was as dismayed as anyone at the slow pace of the city’s response to the broader problem.

“I share the same frustration the city is not as nimble as it should be,” Cedillo said.

The night before the opening, 20 volunteers set out sleeping bags, thick emergency blankets and hygiene kits in the pews of the small A-frame church.

The choir loft was reserved for families who want to stay together, and organizers hoped to accommodate pets, which are banned in most shelters.

Homeless people will sleep one to a pew through the winter, for a total of 30 overnight guests, or more if additional resources become available. If volunteer cooks step forward, there will be dinner through the winter, along with case management to get people on the path to a permanent solution, Prine said.

Though some of northeast Los Angeles’ homeless people come from skid row, most are locals pushed out by skyrocketing rents and building conversions as the area undergoes rapid gentrification, advocates say. The district — which also encompasses Eagle Rock, Cypress Park, Montecito Heights and Mount Washington — had 800 homeless people in the latest tally in January, but only scattered homeless services and little supportive housing.

The city has 26,000 homeless people, including 18,000 who sleep outdoors, according to the most recent survey.

Monica Alcaraz, president of the Historic Highland Park Neighborhood Council, said volunteers had signed more than 400 individuals to a countywide database to match homeless people to services. Only a handful have found housing, and though Los Angeles expanded its winter shelter program, the closest beds are in Glendale — and largely restricted to that city’s residents — or on skid row.

“None of our folks will go to skid row,” said Alcaraz, who works in homeless services and volunteers with Recycled Resources.

“I’ve been downtown. No, thank you,” said Dale Meyer, nursing a third cup of coffee as he slumped in his pew. Meyer, 58, said he was born and raised in Highland Park and ended up homeless years ago after he was laid off from a print shop, one of the city’s many dying industries.

Meyer said he periodically checks into the hospital for treatment of a leg wound. Doctors who discharge him say to stay off his feet, but that’s not possible, he said.

“The way I live, walking, walking all day, it won’t heal,” Meyer said.

Over the last year, Meyer said he’d been rousted from one camp after another, finally landing in a covered carwash. “Throw a piece of cardboard down, put a blanket over me, it ain’t bad,” he said. “You lose track of time. You wake up in the morning, what is there to look forward to?”

Prine hopes to get Meyer into housing before winter ends. As the homeless man settled in for the evening, Prine drove home for a heating pad for one of the women, and Alcaraz went out for Chinese food.

By lights out shortly before 10 p.m., half a dozen homeless people had claimed pews, including a man who called himself Skratch, wearing rags he had fashioned into a sketchy pair of pants and a cape. Organizers said they expected more people as the word spread the shelter was for real.

“We have so many empty buildings, other people could do this,” Prine said.

“It’s what churches do,” Prescott said.

Twitter: @geholland

ALSO

San Francisco police chief urges stun gun use after shooting

A deal to remove four Klamath River dams is in danger of collapse

Wettest start to an El Niño season in Pacific Northwest as storms hit California

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.