Big Sur lost a bridge and slipped back in time. Now residents are wondering what happens next

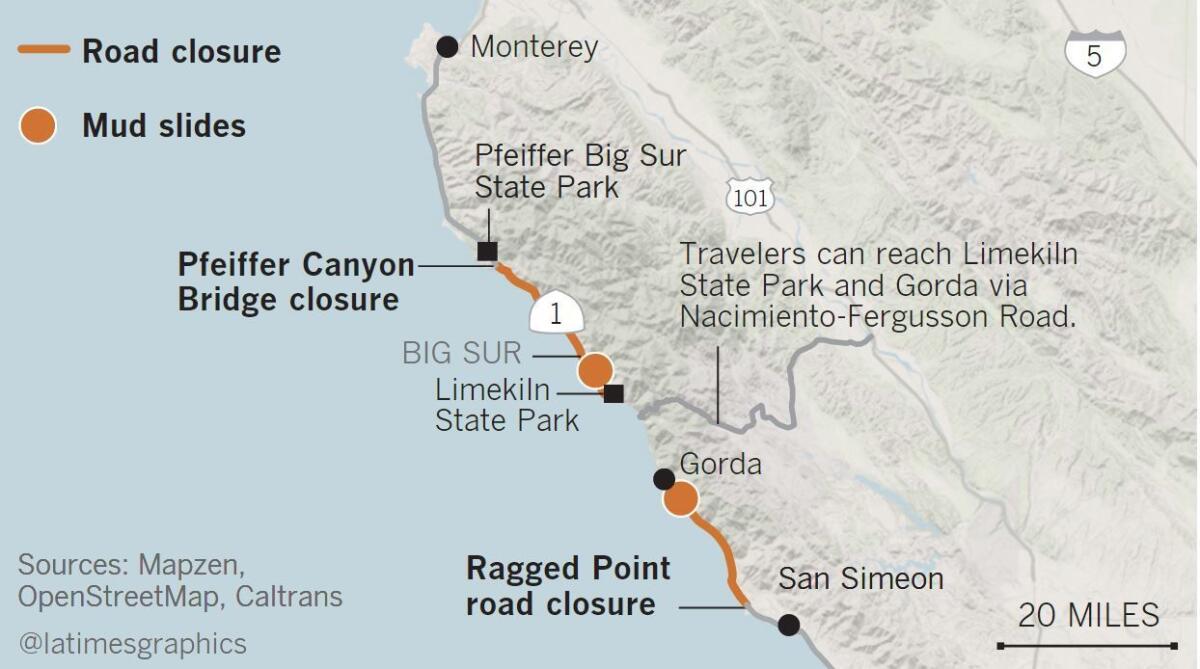

For more than a month, Highway One has been closed at the ruined Pfeiffer Canyon Bridge north of Big Sur and to the south where landslides have undermined the roadway. (Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

Outside the Big Sur Taphouse, a little before 9 p.m., the hint of marijuana is in the air. A country-psychedelic-surf rock band from Monterey plays on an iPhone propped on a stone ledge, and Blake Cusack is skipping rope in the parking area just off Highway One.

“Thirty-six, 37, 38.”

Cusack hopes to hit a hundred, and there is little to distract him, neither the sweep of headlights nor the swoosh of passing cars. The road is dark, and the night is silent but for the hushed voices of the few locals who have gathered beneath the stars.

This is a rare moment in their lives. “You can hear the birds,” said Cusack, taking a break from his exertions. “You can hear lizards running across the road.”

For more than a month, the highway has dead-ended just up the road at the ruined Pfeiffer Canyon Bridge and far to the south where landslides have undermined the southbound lanes. Fences and traffic cones block the cars that carry the visitors who would normally swarm to this treasured stretch of coastline. With only residents getting through, Big Sur has slipped back in time.

Conversations spring up on the highway. Wildlife emerges from the hollows, and the community, once at odds over the traffic and congestion, has found solace in the touchstones of its past: the sound of surf, of rushing creeks, the solidarity of their isolation.

“It’s like being in the Hobbit,” said one man watching Cusack. “Everyone knows everyone.”

But they know this idyll won’t last long. Caltrans hopes to open the highway to the south by June and the new bridge by October, and until then the quiet that’s returned to their lives reminds them of what they’ve lost.

Once a haven for the self-reliant, Big Sur has grown dependent upon outsiders.

The community is home not just to ranchers and hermits, artists and poets, but also retirees and refugees from Hollywood and Silicon Valley, jewelry and book sellers from Chicago and Florida, masons and irrigators from the Santa Ynez Valley, executive housekeepers from Mexico, chefs from El Salvador, mushroom hunters and skiff fishermen from the Monterey Peninsula, interpretative rangers from Oregon and the Bay Area.

Their interests are divided, but they also know they share common ground.

Most came from elsewhere, drawn by the promise of a more simple, more free, more creative life — or merely the prospect of being left alone — but the outside world is chipping away at all that and now seems like the time to ask why.

Once a haven for the self-reliant , Big Sur has grown dependent upon outsiders.

Not everyone agrees when Big Sur started to change. Some say it was at the onset of the drought when California’s endless summer became truly endless. Others point to the proliferation of cell phones when every headlong vista made its way around the world over Facebook and Instagram.

What was once a seasonal destination became year-round, with summers the worst: bumper-to-bumper traffic jams into Carmel, turn-outs used as parking lots and toilets.

Last summer’s Soberanes Fire was the most flagrant insult, a historic inferno started by an illegal campfire that turned mountains into ash.

When the rains came, they fell first as a balm, extinguishing the embers, but then they didn’t stop. One storm after another plowed into the coast with increasing intensity, 83 inches of rain in all. Creeks and springs exploded, and the land did what the land always does. It started to slip and slide.

Pummeled to the north and the south, Highway One was the conspicuous casualty. Then a landslide in the Big Sur Valley pushed a column supporting the Pfeiffer Canyon Bridge off center. The innocuous span started to sag, and within days it was condemned.

“Entropy out here is pretty strong,” says Richard Wangoe, who lives on 54 acres above Hot Springs Canyon. “Nature presents so many challenges to us that it’s a dynamic dance.”

Wangoe, 58, came to Big Sur as a child from Carmel, and like most residents, knows by heart the years of each major assault — ’83, ’98, ’08, ’16 and now ’17 — the fires and floods that continually shift the equation of what it means to live here.

“People have to commit,” said Jeannie Alexander, a resident of nearby Partington Ridge. “If you can’t, people will thin out very quickly when things like this happen.”

That commitment is being tested at Deetjen’s Big Sur Inn, a collection of rustic cabins in Castro Canyon built in the 1930s and listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The storms and falling redwoods destroyed several buildings. “Having lived here for 35 years, nothing is new to me,” said Doris Jolicoeur, 64, in charge of hospitality.

Standing amid a bloom of Chinese magnolia, camellias and rhododendrons, she says, “This place is like a sanctuary.”

I see Big Sur as less a place than a being. The energy calls people here and brings up what needs to be brought up within yourself.

— Ab Plosaj, who works at the Henry Miller Memorial Library

A week into their confinement, residents began to show the signs of cabin fever.

Posters began appearing, inviting the community to gather at their new cul de sac. The appeal — come watch the bridge fall — was strictly a goof; at the time the bridge only sagged, but that was hardly the point.

The highway closures have isolated 350 residents, and organizers wanted to find an occasion to share food, solve problems and dispel rumors. The next week they got together on the promise of seeing the apparition of Jesus.

The third gathering, almost a month without mail, trash pick-up and propane deliveries, drew a smaller crowd even though Big Foot was rumored to be near.

“Who wants cookies?” asked Alexander with the Big Sur Voluntary Fire Brigade. She brought out two plates heaped with her gluten-free peanut butter recipe. On either side of the bridge, crews prepped for demolition.

Alexander set the plate on the tail gate of a truck, and soon the conversation turned feisty.

For weeks, the community had wanted a path cut through Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park to connect the south and north sides of the bridge. Almost 80 volunteers were ready with McLeods, clippers, machetes, folding saws and shovels in hand.

But California State Parks said no. The habitat, nesting birds, archaeology and hydrology had to be studied. A 3-foot-wide trail, a half-mile long with shoring, steps and graded switchbacks, would take five weeks to build.

Community leaders scoffed; they could do it in less than a week. Someone blasted the park service as “a woolly mammoth” devoid of common sense. A week later, the tone was more conciliatory as crews and volunteers worked 10-hour days through weekends to put the path ahead of schedule.

The frustration, however, comes with the reminder that to live in Big Sur means living like colonists, under the control of federal, state, county agencies.

“We’re unincorporated,” said resident Butch Kronlund. “That’s one of the problems of Big Sur. We have so many governmental overlays. We have between 20% to 25% private lands. We’re small in our holdings, surrounded by big public lands.”

Kronlund talks about the privilege to live here, and he takes the responsibility seriously. But he grows annoyed when the government agencies don’t reciprocate and seem to overlook the needs of the residents.

“We’re a flea on the back of a dog,” he said. “We’re 1,500 people versus the millions of visitors a year who come to Big Sur. Who’s the constituency they’re serving?”

On the Monday before leaving on vacation to Hawaii, Holly Fassett, a second-generation owner of Nepenthe, Big Sur’s well-known bar restaurant and bar, has been on the phone with the bank for two hours trying to make arrangements to pay bills online.

“We have to learn new ways to do things,” she said. “We can’t make a plan. Nothing is predictable.”

Sitting at her desk opening emails, she looks out through a scrim of oaks to the Pacific, a bright mirror of sunlight.

When Fassett first heard that the bridge was ruined, she picked five calla lilies from her garden, tied a green leaf around them and placed them inside the yellow caution tape. She apologized to the bridge for having taken advantage of it all these years.

Fassett, 73, came to Big Sur in 1947; her parents opened Nepenthe two years later. She remembers closing up during winter, a time for ping-pong with writer Henry Miller, for listening to scratchy radio sets, playing dominoes, painting and writing.

This year’s road closures reminds her of that. Two nights before, they barbecued on the terrace — tri-tip, roasted potatoes, carrot salad and Fassett’s apple galette — and as more Jameson’s was poured, the party grew more festive. A fire was built to fend off the chill, and young children played tag among the adults.

“This town really knows how to throw a disaster,” someone exclaimed, a familiar line in the wake of each fire or flood.

Just weeks ago, said Fassett, the place was packed with visitors. She recalls when she was growing up her father calling out to the children, “I’m going to take a nap, wake me up when we have seven cars in the parking lot,” or when business was slow, saying, “C’mon, we’re going for a quick dip” and driving them to the Big Sur River.

They don’t have that luxury any more.

From his office, Fassett’s son and Nepenthe’s general manager, Kirk Gafill, whose wife and son are staying in Monterey, could be heard talking on the phone. “The trail is still closed … mired in state bureaucracy … no news on the bridge ….”

He has been charting the economic effect of the closures, and it doesn’t look good.

With Nepenthe, Deetjen’s, the Ventana Inn and Post Ranch Inn shut down, he estimates “an aggregate loss of about $320,000 per day in total sales revenue,” more than $2 million a week, and Monterey County — with its 10.5% hotel room tax — stands to lose $20,000 a day, money applied to its discretionary fund.

The sun is warm and the sky the color of a robin’s egg streaked with contrails, a perfect day for repairing storm damage or getting caught up on deferred maintenance.

At the Post Ranch Inn, they’ve drained the infinity pool and are varnishing the chaises and pool chairs. At the Ventana Inn, they’re clearing brush for the next fire season, and at Esalen, they’re planning their spring planting.

The busyness, however, has a leisurely pace. Workers, unshaven and out of uniform, eat lunches where guests would be checking in and watch children, happy and bored to be out of school. They are the lucky ones, to be working.

In the Coastlands tract just north of Nepenthe, Patte Kronlund is on the phone. The dining table is covered with papers related to the closures, and the storage bin on the floor? That’s from the Soberanes Fire, she said. If Big Sur were to have a mayor, the Kronlunds would be good candidates.

Having helped coordinated the March 3 airlift from Carmel bringing food and medications to nearly 60 families on this side of the closure, they are now trying to raise funds with the help of the Community Foundation of Monterey County for workers who have been furloughed due to the road closures. To date, they’ve sent out nearly 350 relief checks totaling nearly $150,000.

“We’re estimating about 1,000 people who are now unemployed or underemployed,” said Butch, “and considering their families, that could mean up to 5,000 people who are affected until unemployment kicks in.”

As Patte takes another call, Kronlund, a general contractor, steps outside to check on the repairs being made to the community waterline, which was severed by a landslide above Post Creek.

In 1980s, concerned that Big Sur would become as spoiled as Lake Tahoe with motels, condominiums and shopping centers, photographer Ansel Adams and Sen. Alan Cranston proposed a federal management plan for the coast.

Local representatives fought them and won. In the aftermath, though, Monterey County adopted a land use plan that was described as one of the most restrictive in the state, going well beyond the state’s Coastal Act.

“It was an era of civic activism that is continuing today,” said Kronlund, who believes that it’s time to reevaluate how the region is managed.

Highway One was built in the 1930s and is, according to Caltrans, used by more than 875,000 vehicles a year.

“We have to start inaugurating methods to regulate the flow of people and the numbers,” said resident Heather Chappellet-Lanier.

Solutions range from the modest — left-turn lanes at popular crossroads — to the more ambitious, such as a shuttle to take visitors down Sycamore Canyon Road to Pfeiffer Beach, one of most popular destinations. Some would even like to see toll booths at San Simeon and Point Lobos.

Gafill, however, argues that Big Sur’s challenges have less to do with the number of visitors than the fact that in the last 30 years, government agencies have consistently cut back on money for services while visitors have consistently heaped demands on the area’s roads, turnouts and public beaches.

“So the notion of artificially reducing the volume through constraints such as toll roads, guest passes, shuttle systems, I think those are premature concepts.”

He believes that better communications between agencies, more consistent law enforcement and public-private partnerships could remedy some of the problems. But he admits that finding a consensus will not be easy.

“There is no one property owner that owns this highway access or the property surrounding it,” he said.

Mike Linder, a land-use attorney and property manager who came to Big Sur in 2009 when he was 27, sees the region as a case study for larger problems of the planet.

“We can’t have infinite growth in a finite biosphere,” he said.

Down the road at the Henry Miller Memorial Library, Sarah Shashaani and Ab Plosaj are cleaning the archive room, sorting through paintings, posters and books. Peruvian cumbias plays on a laptop. Plosaj, 23, discovered this stretch of the coast five years ago.

“I see Big Sur as less a place than a being,” she said. “The energy calls people here and brings up what needs to be brought up within yourself, and if you show up for that, there is a lot of healing that can happen.”

She credits this capacity to the emptiness of the Pacific stretched to the horizon.

Back at the Taphouse, however, introspection will have to wait. REM’s “Losing my Religion” is playing inside where the jump-ropers stand around a table for a round of Jenga. In the quiet of the bar, they’ve become proficient and hope to break the world record of 41 levels.

While the bridge is out, they just might have a chance.

Twitter: @tcurwen

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.