California Journal: Santa Cruz Water School: A reeducation camp for water wasters

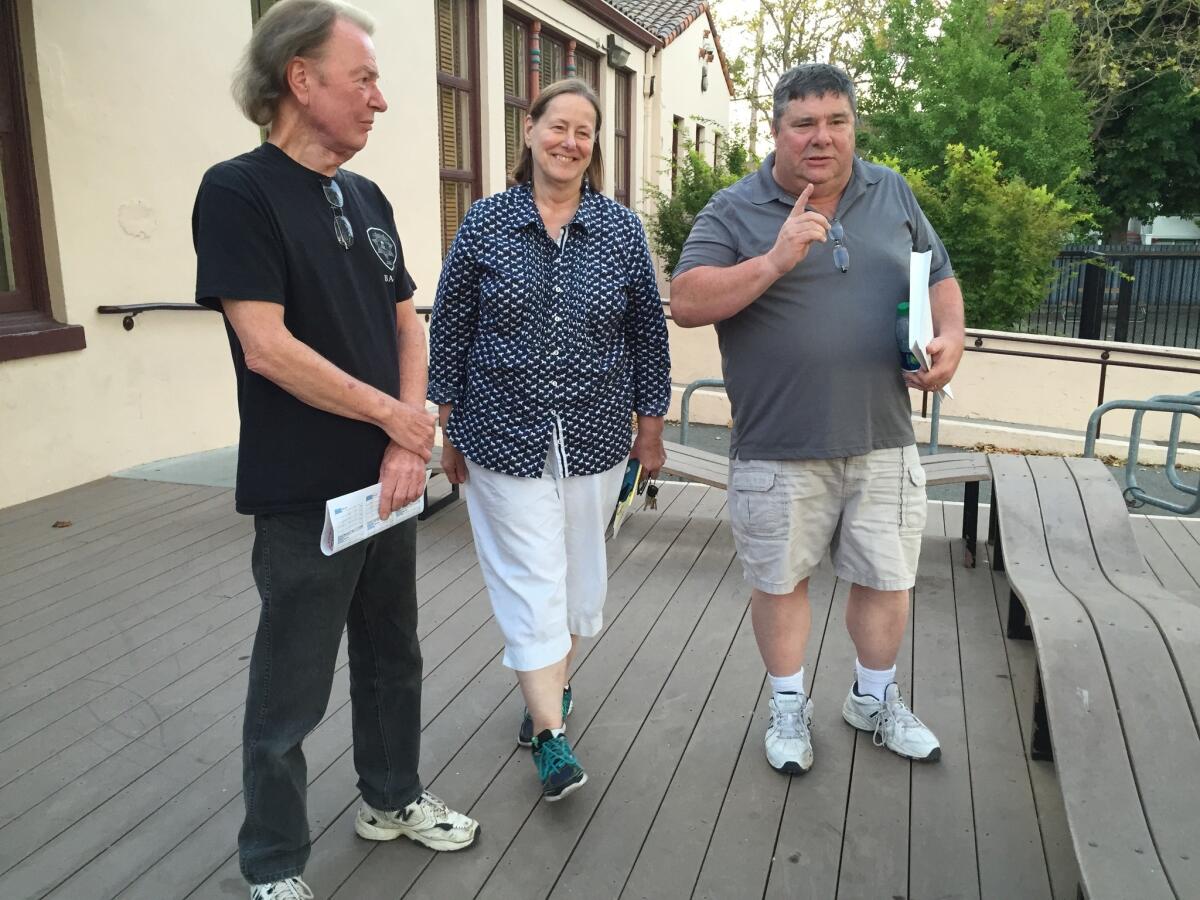

Bruce Wildenrod, left, Lee Heathorn and Mark Zevanove are shown outside Santa Cruz’s community center after a two-hour Water School. Their residential development, Paradise Park, was fined $20,000 for exceeding its water allocation.

Reporting from Santa Cruz — They were summoned to Water School because they had a leaky toilet. Or perhaps they had turned on the vegetable garden’s drip irrigation and left town for a few days. They might have let a painter prep their house with a high-pressure water hose. Or had a broken sprinkler that created an invisible swamp in the yard.

All had committed the sin of using too much water.

Did they scream when they opened their June water bills and found fines ranging from $25 to $20,000?

“I was pretty shocked,” said Lee Heathorn, treasurer of the 387-residence Santa Cruz County subdivision slammed with the largest fine. “But we knew it was coming.”

Likewise, Barbara Canfield, was expecting the $625 penalty for using almost twice her limit. “Someone from the water department had already come to my door to tell me so I didn’t have a heart attack when I opened my bill,” said Canfield, 72.

She is not profligate with her water, by the way. While she was out of town, some transient campers had commandeered her spigots for their showers. The spigots are now locked. And good luck to any water thieves trying to scale her new, 12-foot fence.

In May, for the second year in a row, Santa Cruz has imposed a strict water rationing program. Users who exceed their rations of about 60 gallons per person per day are hit with hefty fines.

But there is a way out.

Once, and only once, the penalty is forgiven if water outlaws attend a two-hour PowerPoint presentation at the local community center.

They learn where the water comes from, and how the drought has imperiled the supply. They learn to check for leaks, to recycle shower water, and most important, to read their water meters. They learn that washing machines account for 18% of residential water use in Santa Cruz, that they should kill their lawns and save their trees. They learn that state law requires all hoses to have nozzles, which was news to me.

The session was dreamed up by the Santa Cruz Water Department’s drought czar, Toby Goddard, who says things like, “To understand Water School, you have to understand rationing. To understand rationing, you have to understand our water shortage contingency plan.” He knows this stuff is abstruse. “Let me not be tedious,” he said, giving me the short version.

Water School serves a dual purpose. First, it educates the water wasters. “The idea,” Goddard said, “is that we don’t hear from you again.”

Second, it serves as a kind of self-defense for the city’s overwhelmed bureaucracy. When the city slaps you with a fine, it must offer the chance to appeal. In the last drought, Goddard said, the appeals caseload lasted way longer than the drought. Water School washed away the appeals backlog.

::

Santa Cruz is something of an anomaly on California’s remarkably over-engineered water grid. It sits on Monterey Bay at the foot of the Santa Cruz Mountains, isolated from the rest of the state’s supply.

Its 95,000 residents are dependent on rainfall that swells the San Lorenzo River and a collection of other streams to the northeast. When there is no rain on the west side of the mountains, the city is in trouble.

Normal rainfall is about 31 inches per year. It was down by a third this year. There was a big rain last December, raising water levels and hopes. But in January, zero.

Goddard is unimpressed by speculation about a coming El Niño, the ocean warming pattern that produces record winter rainfall.

That sort of optimism, he thinks, is simply the opposite of the doomsday scenarios predicting an end to California’s water supply within a year. He recently got an email about El Niño from the National Weather Service. The message: Don’t count on it.

Goddard is focused on one principal goal: Making sure the Loch Lomond Reservoir has enough water to get through next year if the rains don’t come.

Water School helps a little.

::

On Monday, Goddard wasn’t sure what kind of crowd to expect. Would people be angry? Recalcitrant? Resigned?

“Rationing is difficult for our customers, it’s difficult for us,” he said in his office a couple of hours before the season’s first session.

Water scarcity is not just a technical problem. It is a profoundly emotional issue as well. It hits us at the intersection of individual behavior and community welfare. This is not an unfamiliar theme in California, as anyone who has followed the debate over mandatory vaccinations will know.

Last month, Goddard gave a presentation about Water School to a meeting of the American Water Works Assn. in Anaheim. One of his slides, “What was the response?” shows a woman in a “Home Alone” pose, hands on shocked face. The slide outlines a water waster’s “stages of change” -- from shock, self-doubt and disbelief to acceptance.

Another slide, “I am Exceptional,” listed some of the reasons people give for using more than their share of water: I have chickens. I have a wedding to throw. I have a housekeeper. I have butterfly eggs.

“Let’s see if we get any emotional transformation tonight,” Goddard said.

He had already met that morning with Heathorn and two of her colleagues to discuss their $20,000 mega-fine. They were stuck in the shock and disbelief phase.

They live in Paradise Park, a community in the Santa Cruz Mountains that was founded in 1924 by Fresno-based Freemasons seeking escape from the Valley heat. The 387 dwellings, many occupied year-round, are served by only two water meters, which, for technical reasons, means each household is allowed half the allotment given to homes with individual meters. (I could explain, but let me not be tedious.)

“It’s cool we can get the penalty removed, but it’s only a one-time thing,” said Mark Zevanove, chairman of Paradise Park’s newly founded Ad Hoc Water Committee. “We are not going to agree to pay any of these fines because we think we are way under-allotted.”

In class, Zevanove defended Paradise Park’s excessive summer water use by claiming the community uses far less than its allotment in the winter months. “Why don’t we get a benefit for the months that we are below?”

Goddard was blunt. “We’re not in a supply crunch in the winter,” he said. “We’re in a water crunch now.”

The 20 or so who showed up did not seem overjoyed to be in the stuffy classroom. Most were middle aged or older, and from what I could tell, none had committed intentional water crimes.

“Seems like a one-time disaster for everyone rather than chronic overusage,” said Bruce Bridgeman, a UC Santa Cruz professor emeritus who had accidentally overwatered his vegetable patch.

“The class is wonderful,” said Janet Rilliet, who said she knew she and her husband, Walter, were taking a chance when they allowed their house painter to use a high-pressure hose to prep the exterior. They exceeded their water limit by 40% and were fined $175. “They should advertise it. They’ve done a really good job.”

“Of what?” her husband asked.

“Of helping us save,” replied Janet, who said the house looked great, despite the dead lawn, the dried-up fish pond and desiccated fuchsias.

Last year, about 700 people, 7% of the department’s customers, attended Water School, saving $400,000 in fines. So far this year, only 3% have exceeded their allotment. “There is less confusion,” said Goddard. “People know the drill.”

Class ended jovially, with a multiple choice quiz. I don’t know if there were any emotional transformations, but everyone went home with a prize: A small packet of toilet dye, to detect leaks. And, then, of course, to fix them.

Twitter: @AbcarianLAT