Reaching voters the old-fashioned way: canvassing, calling and, yes, even suing to register jail inmates

With three days to go until this execrable election bites the dust, I decided to meet up Saturday with activists at the ground level, people idealistic enough about the democratic process to spend time knocking on doors or making phone calls for the causes they support.

In Long Beach, I walked around a low-income neighborhood with community organizers pushing various propositions. In South Los Angeles, I popped into a phone bank, where young Latinos reached out to their peers, asking them to support my favorite proposition, No. 64, which will legalize, regulate and tax marijuana.

Younger Latinos, polls show, are wildly enthusiastic about this measure.

Their parents? Not so much. Their grandparents? Hardly at all.

Which is why veteran Latino activists decided to focus on catalyzing the millennial vote, rather than motivating older Latinos, who helped sink legalization the last time it was on the ballot, in 2010.

The trick to selling the measure this time is to convince voters that people of color have paid a far higher price for breaking marijuana laws than whites. They are arrested and incarcerated at a much higher rate than whites for marijuana crimes, despite the fact that usage rates are the same across the board.

“Focusing on the criminal justice aspect is the easiest way to approach this conversation,” said Armando Gudino, of the Drug Policy Alliance, a drug law reform group that is a major Prop. 64 backer.

If it passes, the Adult Use of Marijuana Act will erase most marijuana crimes from the books, and allow people who have been convicted of those crimes to have their records expunged. It also provides that minors caught with marijuana will no longer be charged with a crime or infraction. They will be required to undergo drug education and perform community service.

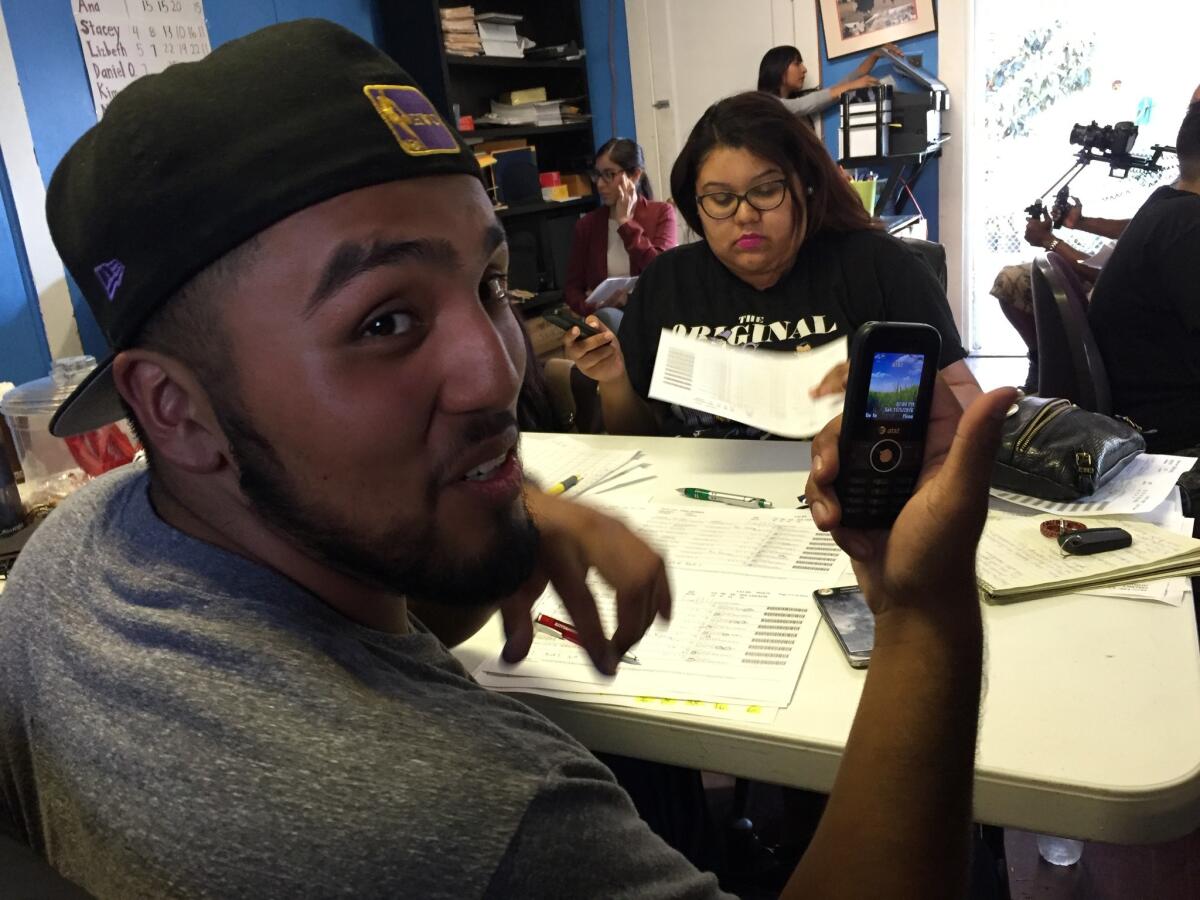

“The message that works is telling people that this law gives our youth a second chance,” said Janet Martinez, of the Latino Voters Initiative, who organized the pro-64 phone bank in a house south of Exposition Park that is normally the headquarters of a civil rights group that works on behalf of indigenous Mexicans. “Instead of making them go into the criminal justice system, give a kid a chance!”

At a table in the living room, Kim Zamor, 26, sat with three other phone bankers. She had a phone to her ear, and systematically went down a list of Latino voters, none older than 26.

“May I speak to Christopher?” she asked. “May we count on your support to tax and legalize marijuana? OK. Is there anyone else in your household who supports it? Your grandma? Great.”

Sitting across from her, 19-year-old Alfredo Campos looked up. “Half the time I don’t even finish my sentence and it’s all, ‘Hell, yeah. We’re supporting it. We’re all pot heads.’ ”

::

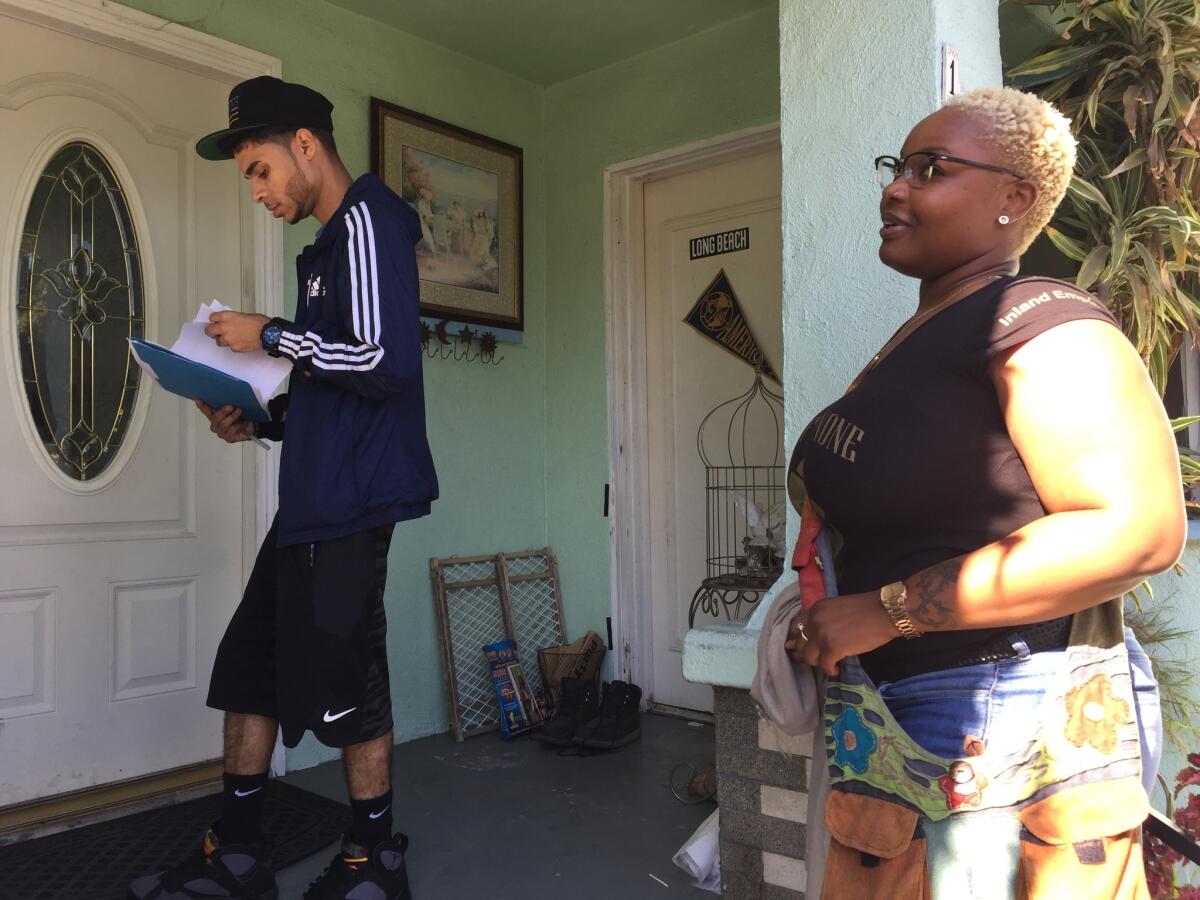

Twenty miles south, in Long Beach, Amber-Rose Howard, 30, went door-to-door handing out leaflets for Prop. 64.

A community organizer with A New Way of Life and All of Us or None, two advocacy groups that help people who have been incarcerated, Howard has been promoting Proposition 64 for months. She has spent a lot of time talking up the measure in black churches in Los Angeles and the Inland Empire, where she lives.

Just like older Latinos, she said, older African-Americans also resist legalization.

“Churches are turned off by it,” she said. “I try to help them understand that it will protect our youth. You know, the war on drugs did a good job of turning people against our youth.”

Saturday, she joined forces with organizers Marlene Montanez, 27, and Wendell Sherman, 22, from a voter engagement group called Long Beach Rising. Montanez and Sherman were pushing Propositions 55, 56 and 57 (which will retain a higher tax rate for the rich; increase the cigarette tax; and let judges, rather than prosecutors, decide whether to try juveniles as adults).

In this part of Long Beach, south of Long Beach Polytechnic High, it’s hard to tell sometimes when people answer a knock. The screen doors are heavy and made of metal mesh. Someone opening the door can see you, but you can’t see them.

Another problem: the occasional excited dog, who rushes onto the porch to see who’s visiting.

“I do not like dogs,” said Howard.

On Olive Street just south of Anaheim Boulevard, Howard and Sherman knocked on a door looking for a voter named Keith Russell. “He’s not home,” said a middle-aged man, stepping onto the porch.

“Do you mind if I leave you some information about Prop. 64?” asks Howard, handing the man a flier. “Are you registered to vote?”

“I did time,” the man replied. “They aren’t interested in me.”

“You can vote if you did time in prison,” said Howard. “I served time for a felony, and I’m registered to vote.”

The man shrugged and went back inside.

This was a bit frustrating for Howard.

Last month, Howard and All of Us or None sued Los Angeles County Sheriff Jim McDonnell and Los Angeles County Registrar-Recorder Dean Logan in L.A County Superior Court, accusing them of failing to allow eligible county jail inmates to register to vote and request ballots in a timely manner.

As it happens, inmates who are awaiting trial or serving misdemeanor sentences are not just eligible to vote, but according to the registrar’s website, are encouraged to vote. (Currently, inmates who are serving time in county jails for felony convictions may not vote, though they will be eligible in January under a new state law.)

The case was settled less than 10 days after it was filed. So far, All of Us or None has registered 804 county jail inmates.

I could be wrong, but I bet that’s another 800 or so votes for Proposition 64.

To read the article in Spanish, click here

Twitter: @AbcarianLAT

ALSO

In final weekend, Clinton focuses on her ‘firewall’ while Trump hits battleground states

Skelton: Need guidance at the ballot box Tuesday? Four final takeaways to help you cast your vote