He challenged himself to build an ADU for under $100,000. What’s his secret?

In 2019, Alexis Navarro set out to fix a problem that had plagued his rental property for years: inefficient and ill-considered design.

Navarro grew up in East Los Angeles, and when he became a landlord there, he says, he found himself struggling to create intelligent low-cost housing solutions for the low-income rental market.

“I am Mexican. I was a first-generation college student, and I teach at East Los Angeles College,” says Navarro, 62. “I feel connected to the community. It’s personal for me.”

His epiphany occurred shortly after he purchased a remodeled triplex on a 5,800-square-foot lot in East Los Angeles. The property comprised a duplex with side-by-side, one-bedroom apartments in front and a freestanding two-bedroom traditional house at the back of the plot. The rental units were move-in ready, but when Navarro learned that two of his tenants were sleeping in their living rooms because the bedrooms were too narrow for their beds, he was disappointed. “They were paying me all this rent and they couldn’t use the house comfortably,” he says.

As a professor of architecture and design with a working-class background, he says he found himself thinking: “‘How can I design and build something that is low-cost and attractive for people who can’t afford quality living spaces?’ That’s what prompted me to build an ADU.”

Navarro’s quest arrives in the midst of a housing crisis so severe that the city of Los Angeles has turned to accessory dwelling units, a.k.a. “granny flats,” as part of the solution. On March 5, the city launched the ADU / Standard Plan Program — an initiative that offers homeowners and builders access to a variety of preapproved ADU building plans and designs to allow for faster and less expensive permitting.

Los Angeles has launched a program with over a dozen preapproved designs from top architects for backyard dwellings, cutting the bureaucracy for needed housing.

And although some hail that as a helpful step, and one that trims costs, it can still be expensive to build an ADU, with the price tag between $100,000 and $350,000.

Enter Navarro, who has worked as a team member for the Getty Center with famed architect Richard Meier and who believes he has beaten the city at its own game: His ADU also simplifies design and building and manages to come in at less than $100,000 while providing a living room, bedroom, kitchen and bathroom in 536 meticulously planned square feet.

In experimenting with everyday construction, Navarro reminds us that good design doesn’t have to be expensive.

“I wanted to get that post-and-beam feel without post-and-beam construction, which is more expensive,” he says. “I used conventional two-by-four wood construction, which is a game-changer.”

ADUs, which account for 22% of newly permitted housing units, are not just about density in the physical sense, said architect John Southern, principal of the architecture and design firm Urban Operations and adjunct professor at the USC School of Architecture, but affordability and equity in the face of NIMBYism.

ADUs, also known as granny flats, are poised to transform neighborhoods across Los Angeles and beyond, as cities look to the compact dwellings as a way to ease the region’s severe housing shortage.

“As an architect who has been producing mainly single-family homes in L.A.’s Eastside over the past 15 years, I have been repeatedly reminded of how backward L.A.’s antiquated zoning code is, as well as how it has treated the single-family dwelling zone as a sacred cow,” Southern said in an email. “The result has been an amplification of the housing crisis that has been with us since the Great Recession. The prospect of ADUs acting as a possible wedge solution to the nature of the R-1 residential zone is critical in leading Angelenos toward a more sociologically and economically sustainable density model.”

Working as his own general contractor, Navarro and his design firm ANDesign built the ADU in place of the property’s 35-foot-wide carport in just five months for $95,000, including design, engineering, permits and construction costs. (His tenants who were most affected were given rent credit during construction.) “If I had hired a general contractor, it would have cost between $130,000 and $160,000,” he says. Despite the loss of the carport, each of the units has one parking space — a priority in the confined area.

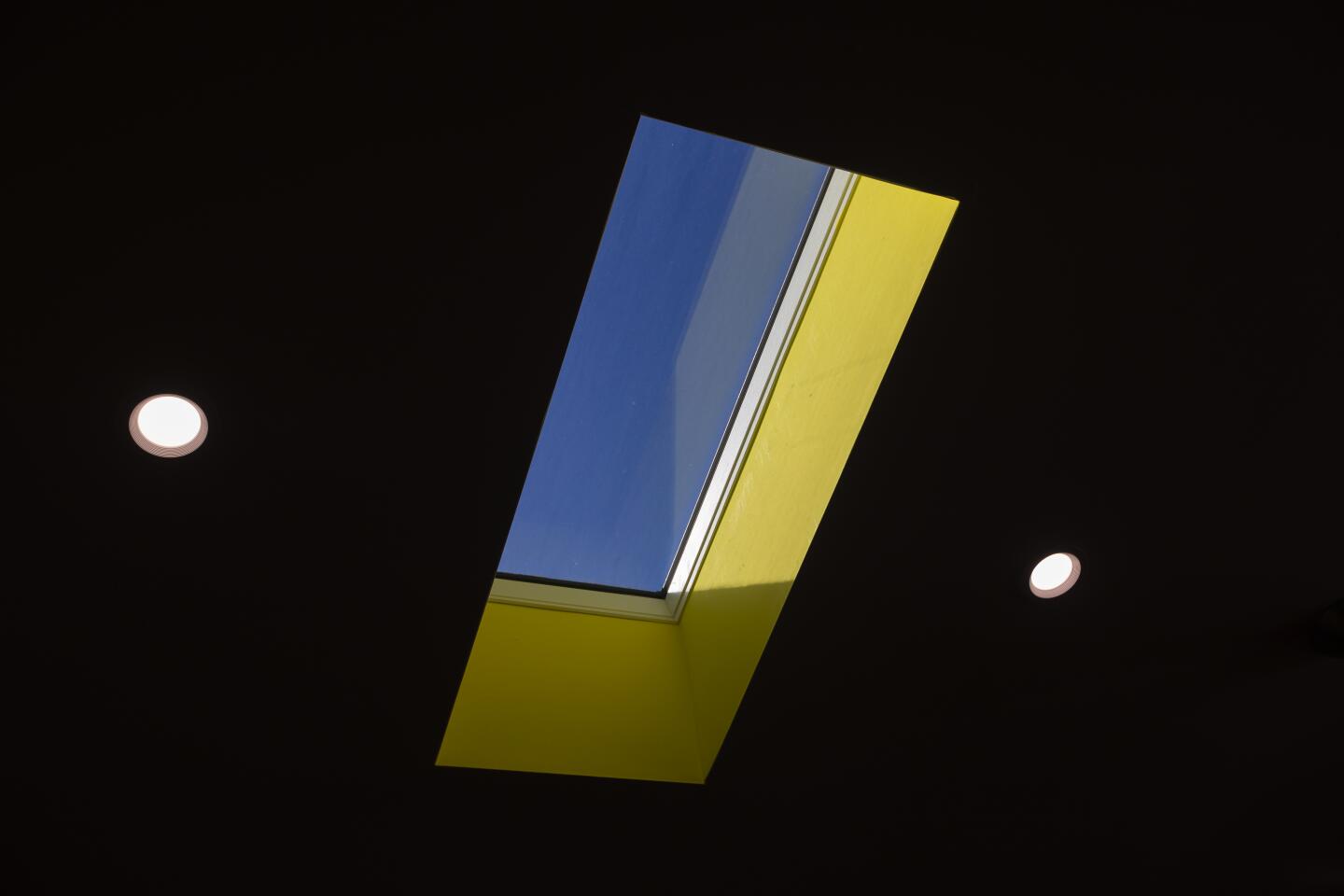

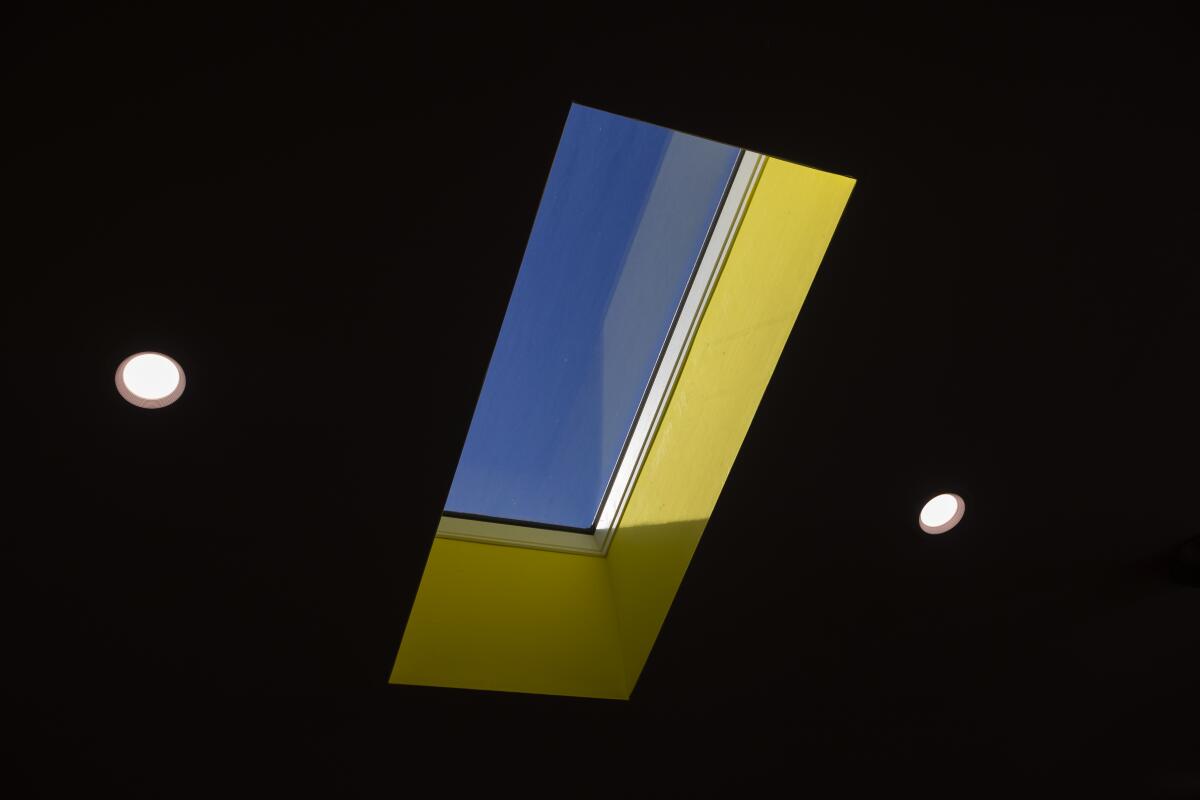

The resulting “Casita L.A.” as he calls it was designed to maximize daylight so the ADU would feel much larger than its 536-square-foot footprint.

Inspired by the Midcentury Modern post-and-beam architecture of Rudolph Schindler, Navarro installed tall cathedral ceilings to increase the volume of the space and make the interiors feel less claustrophobic.

He decided against installing walls because he wanted the occupants, and potential elderly renters, in particular, to enjoy a large open space where they could move freely and create their own small-space living solutions. “It’s meant to be a very casual loft-style house inside a bedroom community,” Navarro says.

Because the ADU is wedged alongside the three other rental units, Navarro wanted to limit the exterior views. As a solution, he installed translucent film on the home’s windows to create privacy while allowing in additional light.

Energy-efficient solutions include low-maintenance raw concrete floors that absorb heat, three operable skylights that can be opened to release hot air, and north-facing glazed clerestory windows to help keep the house cool.

Sign up for You Do ADU

Our six-week newsletter will help you make the right decision for you and your property.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The minimal kitchen features a sink and countertops from Ikea and easy-access open cubes as a substitute for traditional cabinets. Even in the tight galley kitchen, there is room for a compact washer and dryer designed for apartments. The bathroom, the structure’s only closed space, is painted a bold orange to enliven the space and is outfitted with HD Supply tile and basic plumbing and electrical supplies from Home Depot.

“I wanted to build a system that anyone who knows how to build can do,” Navarro says. “This is everyday construction.”

Although Navarro found the acquisition of building permits to be relatively easy in the unincorporated area of East Los Angeles, he acknowledged the difficulty for others who are not experienced in the process.

“It is most definitely an intimidating experience,” he says. “It is even more difficult if a homeowner does not speak fluent English or appreciate the intentions of the planning standards and building codes to protect the public from unsafe and unhealthy conditions. Unfortunately, it’s not streamlined enough and needs to be communicated in easy-to-understand language for the general public, but I do think that building officials have made substantial progress in this challenge recently. I applaud the City of L.A.’s efforts to have developed the prototype ready-permitted set of projects for the public to select from choices of different types, sizes and budgets.”

When Navarro finished, he listed the studio for rent on Zillow for $1,650, which he says is fair for the high-density neighborhood of primarily Latino families who were happy knowing the ADU was going to raise home values in the neighborhood. He was instantly inundated with inquiries from as far away as Thailand and New York.

“Some people thought it was a scam,” he says with a laugh, including his eventual tenants Ariel Gomez-Hernandez, 29, a speech-language pathologist, and John Velasco, 29, an audio engineer.

“We thought it was too good to be true,” confirms Gomez-Hernandez, who grew up in Koreatown and had been searching for an affordable rental for two months. “We thought it was such a cool structure. It looked like an art gallery.”

Yes, the four units are a tight squeeze, Velasco says, “but that’s how I would describe living in L.A. People have lived here a long time. It’s a quiet street, although the music can get pretty loud sometimes.”

That doesn’t bother Gomez-Hernandez, who lived near Little Puerto Rico when she was getting her master’s degree at Columbia University in New York. “I am used to waking up to bachata,” she says. “I like that the house is at the back of the property and off of the street. We don’t hear cars passing by. We can envision living here for a few years until we have a family. Our love language is very similar in terms of physical touch. For now, we are happy.”

During the pandemic, the couple are working from the tiny house along with their dog, Lando; they accommodate each other by wearing headphones. They have one small closet, which they use for their clothes, as well as a wardrobe; they also store items under the bed.

The couple downsized before they moved in and, for the moment, rent a storage unit for $164 a month. “It was liberating,” Gomez-Hernandez says. “We donated a lot of stuff and gave things away. I used to be a bigger consumer. But now when I go to buy something, I’ll think, ‘I don’t have space for that.’ It has helped us save a lot of money.”

Recently, Navarro added an enclosed porch so the couple can enjoy the outdoors. He is using the casita, with some revisions, as a prototype for a client in Granada Hills and hopes to build more in a courtyard setting.

“The patio was a nice addition,” says Gomez-Hernandez. “Alexis knew we were both working from home because of the pandemic and he wanted us to have a private outside space. It was so nice of him to do that.

“When I post photos of my patio on Instagram, my friends always ask, ‘Where do you live? It looks like you’re in Joshua Tree.’

“I tell them, ‘No, this is my home in East L.A.’”

More to Read

Sign up for You Do ADU

Our six-week newsletter will help you make the right decision for you and your property.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.