A UC Riverside researcher may have discovered a way to save our citrus trees

Attention home gardeners: Our beloved citrus trees may yet be saved from the incurable huanglongbing, a.k.a. HLB or citrus greening disease, thanks to natural immunities found in a rare and flavorful relative known as the Australian finger lime.

After five years of study, a team of UC Riverside researchers led by Hailing Jin, professor of plant genetics, identified which gene in the finger lime causes that immunity and extracted it to create an antibiotic that has killed the disease in young trees raised in laboratories and controlled environment greenhouses.

The treatment can be used as a spray or an injection, but don’t go rushing to your garden store just yet.

Get The Wild newsletter.

The essential weekly guide to enjoying the outdoors in Southern California. Insider tips on the best of our beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In a news release, UC Riverside announced it has entered into an “exclusive, worldwide license agreement” with Boston-based Invaio Sciences to produce and market the antibiotic, but Jin said production can’t begin until the antimicrobial peptide (a really small protein) that kills the bacteria has gotten government approval.

That natural resistance is what prompted Jin to study the finger lime, and related plants, to see if she could determine why it seemed immune to HLB infections. She used comparative analysis to look at the plant’s genes to see if she could identify what created the “internal immune response that protected it from infection ... and that allowed me to identify the responsive genes that contribute to these tolerances.”

L.A. gardening guru Ron Finley filmed his gardening MasterClass long before the coronavirus and Black Lives Matter protests. But his message is right on time.

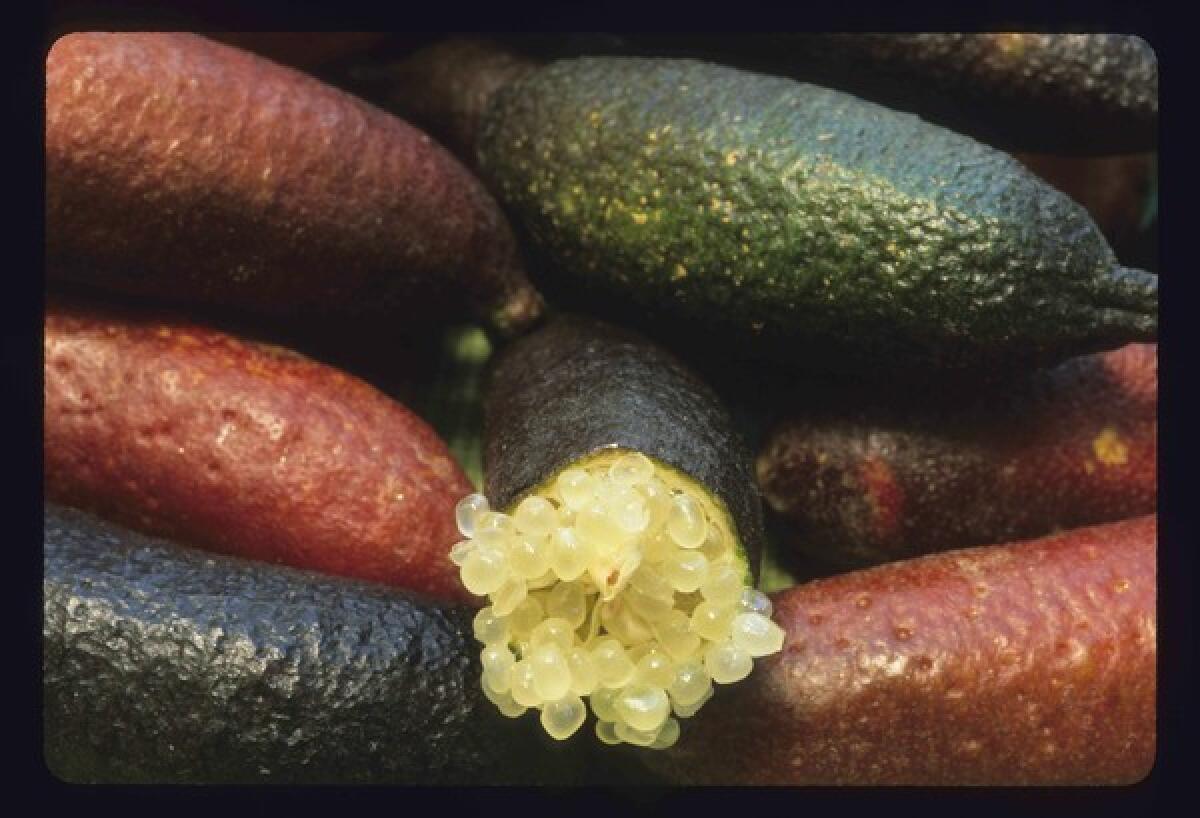

Australian finger limes are also known as caviar limes because once cut, the small, pickle-size fruit spills into tiny caviar-like beads that provide an intense citrus taste. The fruit is expensive but used in many fine restaurants in Asia as a tasty addition to a dish, much like a dab of fish caviar.

Now that researchers have identified the peptide, Jin is hopeful the regulatory approvals will come quickly, since the protein is derived from a natural substance and appears safe to humans. Moreover, she said, the antibiotic is easy to manufacture and continues working in high heat, up to 130 degrees, unlike other antibiotics that become ineffective in warm temperatures.

You’ll have to declare brutal warfare on the ants in your yard while embracing a tiny parasitoid wasp that eats its living prey from the inside out.

But Jin is adamant the treatment should not be called a cure, at least not until she’s completed her tests on mature trees in the field, growing outside of a controlled environment. Those tests were supposed to happen this spring in Florida, where 90% of the remaining citrus trees are believed to be infected with the HLB bacteria, she said, but they have been delayed because of coronavirus shutdowns.

“We were supposed to start the field trials as soon as the pandemic goes away,” Jin said, “but now, with positive [coronavirus] cases surging in Florida, we don’t see how the state will be reopened anytime soon. So we have to wait.”

Still, the Jin peptide is the most promising development in destroying the disease that has devastated Florida’s citrus industry over the last 15 years. The disease ruins the flavor of citrus fruit, so they stay bitter and green, and over time will kill the tree.

The disease is spread by the Asian citrus psyllid, a tiny sap-sucking insect discovered in California around 2008. Treatments to stop the disease here have centered on removing infected trees, spraying with pesticides and using natural predators to kill the psyllid so they can’t spread the disease.

In our Plant PPL series, we interview people of color in the plant world, including plantfluencers, plant stylists, floral artists, enthusiasts, experts and garden store owners.

After HLB disease appeared in Florida in 2005, it destroyed half the citrus industry’s acreage and production, and pretty much eliminated residential citrus, according to UC Riverside entomologist Elizabeth Grafton-Cardwell, director of the Lindcove Research and Extension Center in Exeter. That’s why California’s $1.7-billion citrus industry is willing to do whatever it takes to destroy the disease-spreading psyllid, such as spraying the trees with pyrethroid and neonicotinoid pesticides, which are toxic to bees.

But Grafton-Cardwell said untended residential citrus trees are one of the biggest threats. About 60% of California’s homes have at least one citrus tree, she said (the percentage is higher in Southern California), and the industry has been trying to keep people from planting more to reduce the threat to commercial growers.

The University of California’s department of agriculture and natural resources has created an interactive map that identifies hot zones of infection. In Southern California they’re mostly where Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties meet. Enter your address to see how close your home is to those infection areas.

If you have an infected tree, Jin said the best approach is to remove it because her antibiotic won’t be available soon.

“If you leave a positive tree anywhere, it can serve as a reservoir for psyllid to spread the disease,” she said. “It’s like a malaria-positive person. If one person has malaria in a village, mosquitoes can carry the disease to every other person and infect the entire village. These psyllid can fly pretty far, miles away from an infected tree, so you have to get rid of the source.”

And hope the treatment comes along fast.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.