20 landmarks that underscore L.A.’s pivotal role in the fight for LGBTQ rights

While Pride is celebrated each June to mark the anniversary of the Stonewall uprising in New York City, take some time to also appreciate the rich history of LGBTQ activism in Los Angeles.

We’ve selected 20 landmarks across the city that highlight the work Angelenos have done for decades to fight for the right to exist, to love and to live in peace.

Some locations no longer exist as they once did, but the memory of what happened in these important places has been preserved in books, documents, photographs and first-person accounts.

It’s worth noting that today’s legal weed scene wouldn’t exist without the efforts of LGBTQ activists.

Take, for example, Cooper Do-Nuts, a long-gone 24-hour cafe in downtown Los Angeles where a group of queer people rebelled against police harassment by throwing coffee cups and stirring straws at LAPD officers attempting to make arrests.

The undertold story of that May 1959 uprising was one of several gaps that prompted Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons to write their 2009 book, “Gay L. A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians.”

“We discovered that, historically, more lesbian and gay institutions started in Los Angeles than anywhere else on the planet, and that L.A.’s multifaceted, multiracial, and multicultural lesbian and gay activism continues to have tremendous impact worldwide,” they wrote.

Today, Los Angeles’ LGBTQ history is being preserved by organizations such as the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries and the June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives in West Hollywood (both of which are on our list).

“L.A. is one of those places where things can happen that can’t always happen somewhere else,” said Angela Brinskele, director of communications at the Mazer archives.

Los Angeles has pride parades, pride proms, pride concerts and pride comedy shows planned throughout June.

For Brinskele, maintaining queer history in Los Angeles is about making sure the next generations know that there were others before them and have a sense of the history of the gay rights movement.

“Even today, depending on where you live in the world and what kind of family or religion you’re brought up in, you can still think you’re the only queer person in the world,” she said. “A big principle that we live by is we’re not going to let our history be made to disappear.”

It is with that sentiment that we’ve compiled this initial list of landmarks and points of interest. It is, we know from the outset, far from exhaustive. However, it is a starting point and a list we hope to add to so that the city’s rich LGBTQ history — and the local places where it has been made — never disappear.

The Wall Las Memorias AIDS Monument

Designed by architect David Angelo and artist Robin Brailsford, the memorial features eight panels — six with murals inspired by life with AIDS in the Latino community and two listing names of people who have died from AIDS complications. The 9,000-square-foot memorial includes a park area with benches and a large archway.

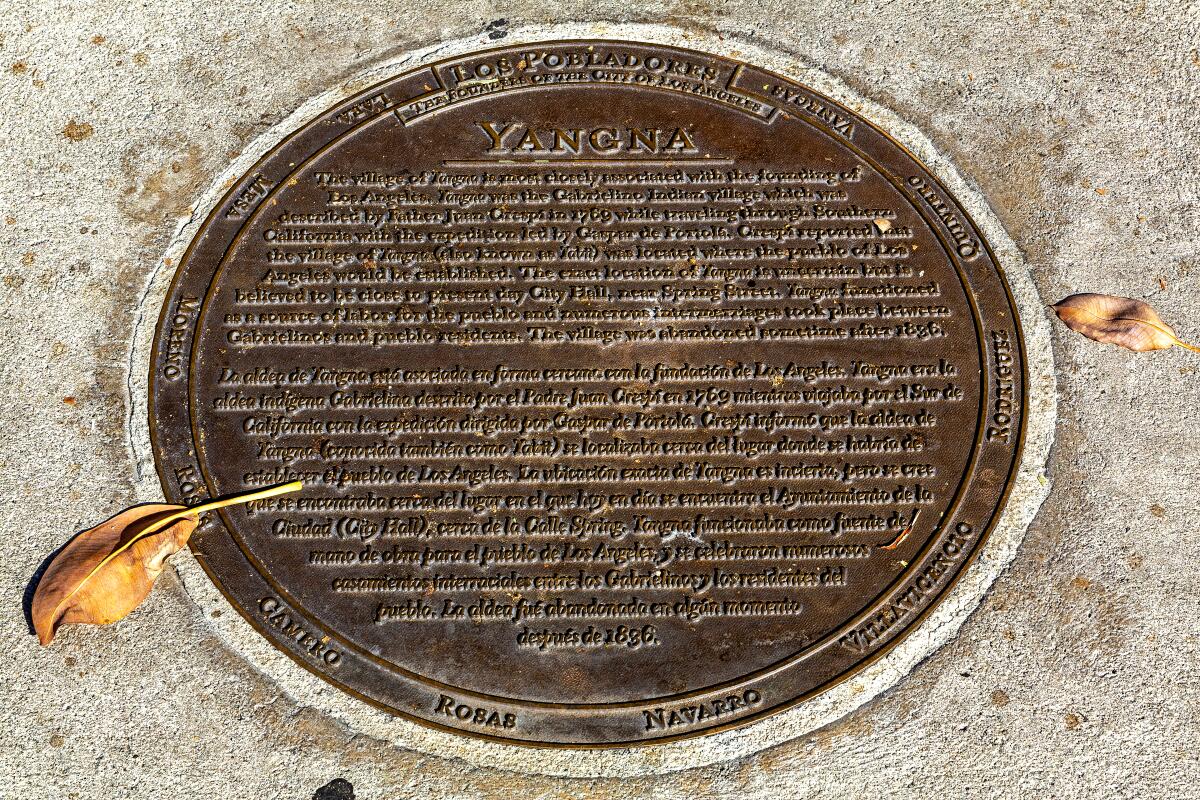

Yangna plaque — El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Historical Monument

The New Jalisco Bar

Cooper Do-Nuts

Pershing Square

First designated as a public space in 1866, the park has had several names, including La Plaza Abaja, Los Angeles Park and Central Park. In 1918, it was named after Gen. John Pershing, who led American forces in Europe during World War I.

Morris Kight's former residence

ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries

Jewel's Catch One

Tom of Finland House

Harry Hay's former residence

Griffith Park Merry-Go-Round

The Black Cat

Paramount Pictures

Los Angeles LGBT Center

Site of the first Pride parade

Last year, the street was the site of racial justice protests and marches after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. On Hollywood Boulevard between Highland Avenue and Orange Drive, a permanent street mural was installed as a tribute to the June 14, 2020, All Black Lives Matter march, which called for LGBTQ rights and racial justice.

Plummer Park's Great Hall/Long Hall

June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives

Beth Chayim Chadashim

Will Rogers State Beach

The Rev. Troy Perry's former residence

Today, the church estimates is has 43,000 members spread across congregations around the world. The Huntington Park home is a private residence, but visitors can attend a service at the congregation’s current location in Los Feliz at 4607 Prospect Ave.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.