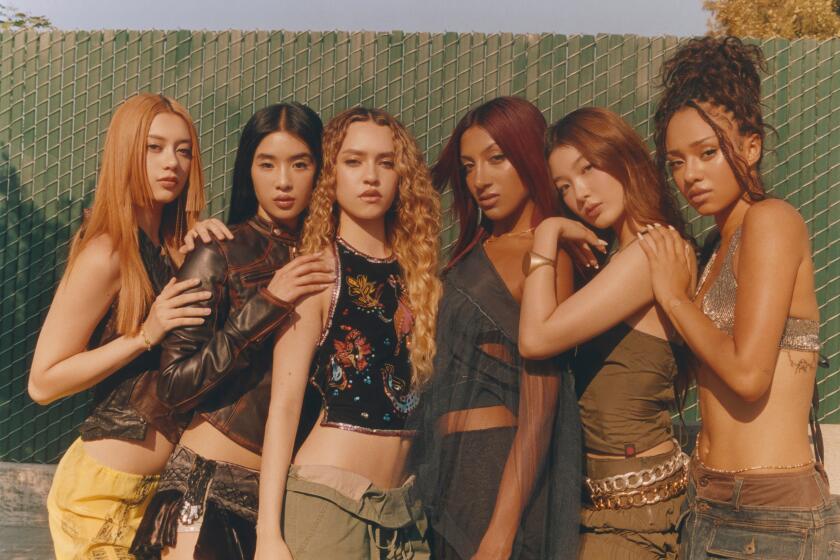

Thumbing through the pages of Frutas magazine feels like dipping into a sensory world of aesthetic celebration. The images draw you in with texture and color: leather, fur, mesh and neon beckon you to take a closer look, to run your hand across the page. L.A. kids wear fits described as “sweet baby metal slut,” “eclectic goth,” “streetwear but make it sexy vampire” or “cyber lolita.” Founded by photographer, director and multimedia artist Bibs Moreno in 2021 with Aloe Garza, Frutas is a living, breathing archive of Latinos and other people of color in L.A. who exist outside the binary, for whom subculture and style are an obvious religion.

Frutas is a movement all its own — but it was inspired by Fruits, the iconic underground magazine that from 1997 to 2017 archived its own technicolor world of style and subculture in the Harajuku district of Tokyo. From Lolita to Decora to Cyberpunk, Fruits became the fascination of generations of culture and fashion freaks by illustrating the anatomy of a cool kid. Moreno discovered it on Tumblr, on one of the countless blogs dedicated to Fruits (not to mention the many that exist on Instagram today). She felt drawn to the loud colors, to the freedom with which these people exhibited where they came from through clothing. Moreno was looking toward Fruits in the same way generations of streetwear kids were looking toward Nigo in the early 2000s. There has always been a symbiotic relationship between L.A. and Japan when it comes to style. Not to mention: “There’s a weird thing with Mexican and Japanese culture going on,” says Moreno.

Moreno’s work has long been focused on uplifting the intricacies of Latino and Chicano culture — Frutas is an amalgamation of this calling, creating a rich, layered text where rockers, Weeaboos and ravers live among the same pages. It’s a small slice of the real universe Moreno lives in. Japanese fashion photographer Shoichi Aoki, founder of Fruits, thought his creation could spur the same epiphanies in readers about his own subjects: “... the important thing is that the world became aware that young Japanese people — who used to be known as homogeneous — are creative and individual,” he told the Face last year.

Moreno scouts every participant and photographs them on her Mamiya Rz67 Pro II using classic L.A. backdrops like Santee Alley, urging models to come as they are. (She currently runs the magazine with her friends Angel Leon and Mayra Baldonado, and Frutas recently started a Patreon.) The point is to capture people and the city in their natural luminosity — creating a record of time and place. Archiving, as Moreno says, is hard proof that we were here, that we were “sick as f—.”

We spoke with Frutas founder Bibs Moreno and Frutas model and staffer Angel Leon about the project.

Julissa James: Tell me about the start of Frutas.

Bibs Moreno: Los Angeles is kind of a glorified suburb. It’s not very bustling like other major cities, especially compared to Tokyo. I was like, “What’s the closest we could get to that?” I thought Los Callejones, to have a lot of things going on in the back, a lot of people. Something that’s very L.A.-coded with the bright colors and the businesses. I went in wanting it to be a Fruits copy, but then, as we started seeing Los Callejones and the friends we had [participating], it was like, “Oh, OK, we’re inspired, but we’re not copying. This is the L.A. version. We’re gonna show what L.A. has to offer.”

JJ: Let’s talk about how the vision started to evolve with the second and third issues.

BM: After dropping it, not to be dramatic, but everyone was really excited. It was a lot of Latinos that were Weaboos [obsessive fans of Japanese culture] or into J-Fashion or just into Japanese culture in general. Seeing that made me realize, “Oh, I’m hitting a niche that nobody is doing and people want this.” Even before Frutas, this has always been a vision for me — that everything I shoot is very Latino-focused. [I] was trying to show alternative artists here in L.A. — me and my friends, shooting the scenes here. I meet a lot of people that come to L.A. from other states, other countries, and think everyone here is a cholo or cholo-adjacent. I grew up in super Chicano culture. But also, bro, we’re not a monolith. I think people even get shocked that there’s a lot of Mexican goths. Mexicans are f—ing rockeros.

JJ: Let’s talk about some of the different subcultures you touch on with Frutas. Because there are so many.

BM: And I feel like I need to expand more. I feel like I’m not even doing enough. Decora. J-Fashion. We did Lolita. We’ve done dome metal foos. We’ve done punk. Goth. A lot of ravers. I should probably shoot some Edgars. I really want to start shooting older people — 40, 50, 60. I want tías. I want mothers. I want an abuela in an apron. I see that so much, that’s their uniform. There’s a comfort in it and their identity.

JJ: What was y’all’s first interaction with the OG Fruits magazine?

BM: Tumblr in 2010, 2011.

JJ: What moved you about these images when you saw them?

Angel Leon: I’ve never really seen people dress like that before. Coming from the I.E., people weren’t really into fashion that way, or self-expression in general. That’s really what captured me — was that everybody had such a unique and distinct style, and I feel like it very much represented them. It inspired me to have a distinct style that felt right for me.

BM: Angel was really cute in high school too. What was it for me? I think the colors, weird accessories, the innovation. The originality, the creativity — taking things you wouldn’t typically think of as something you can accessorize with or use as clothes. It’s an art form in itself.

JJ: I was so drawn to Fruits and equally, if not more so, drawn to Frutas because it’s an archive of a time and place. I think style is such a good indicator of where someone is on the map, what year it is. I just started to think about how important it was for so many of us growing up to have an archive like Fruits, and I think 20 years from now, people will be looking back on something like Frutas and feeling the same way.

BM: I don’t think I went into it with intentions of archiving, but then I was like, “Wow, this is gonna be super cool in the future. Even if it doesn’t blow up, even if it’s just for us.”

AL: In the past, I’ve always been kind of bad about taking pictures and having things to remember. I regretted that I didn’t have things to remind me. This has also inspired me to archive these memories.

JJ: How has archiving as a practice played in each of your lives?

BM: Even before Frutas, I really took on that role as the archivist. Especially with my family now. My tía did it more — the one that bought the camcorder. She’s the one that initiated it. As soon as I got into photography, I felt like that became my role with my friends and with my family. I’ve always been really fond of looking back at pictures. I don’t know if you’ve ever read the book “The Giver.” I really resonate with [it] — the guy that holds all that pain, all the memories while everyone else can live their blissful life. And then he passes it on. I’ve taken photos at funerals of all my family members. It’s painful to be the one photographing that, being responsible for storing that and making the copies and giving them to all my family members so they have it. Astrologically, in my chart, I have a lot of Capricorn placements in my fourth house that deal with ancestry, past life karma. There’s a lot of responsibility on my part for the past.

AL: What really pushed me to archive was when my mom passed, because she had all the pictures of us when we were younger. It meant so much to me to be able to just recall memories that I had with her. And I realized, I want to remember where I’m at right now. Achievements, people, places that I’ve been — experiences in general. It’s so significant. I’d never archived [my life] with pictures before, but I would with music playlists. And I like to do that now with photos.

JJ: I know that Frutas is super community-sourced. Who are the people that are in the photographs? How do you choose them? Are they mostly friends?

BM: It obviously started just with friends. And then it turned into friends of friends or people at parties. And just being a photographer and artist, you start meeting a lot of people and calling them up like, “Hey, would you be down?”

JJ: Why was it so important to make this a print publication versus just something that existed online? Why did you want this to be something that people could pick up, flip through, have?

BM: After the pandemic, people were really tired of cheap clothing, cheap furniture, cheap anything. Nothing of quality. They don’t want just digital things. We were inside and we didn’t have any contact with people, so people were craving physicality a lot. A lot of former models have reached out to me when they get their magazine and it’s really emotional for them. I get people DMing or texting me, “Thank you. It’s so cool to see myself in a magazine.” How did you feel when you got your copy, [Angel]?

AL: That was the first time I’d ever been printed on anything. It brought a sense of importance for sure — for who I am and just my existence.

BM: I really do focus on not trying to shoot too many people that are really Instagram-famous. The Aquarius in me [wants] to highlight everyday people that are sick. It’s not about you being the trendiest — this is your authentic style, and you’re just you, and when people think of you they know. Being able to uplift people — not to sound like I have all this power — but it feels cool.

JJ: It is an emotional thing to be seen. When you shoot people, do you give them a guideline of how to style themselves?

BM: The only thing I tell people is: “I picked you because I like your style. Obviously, this is Fruits-inspired. If you want to do a Fruits look, you can, but absolutely no pressure. All I ask is that you roll up in your favorite fit that you feel the most confident in. Don’t feel that you need to dress any way other than you.” That’s all I ask: just come in the one that’s going to make you feel your best. I’m very hands-off. I’m not going to tell you what to do — do you.

JJ: Walk me through a little bit more of the magazine-making process. Who does what?

BM: Mayra and Angel just got on. They’ve been helping me organize. We just started the Patreon, so they’ll be helping with media. I cast. I produce [the shoot]. I take the photos. I develop the photos. I scan them at home. I lay it out. I retouch everything. I do the website. I’ve been getting into graphic design.

JJ: Do you do the logo? I love it.

BM: Yes. And customer service. And organizing all the parties.

JJ: Let’s talk about the parties. The physical spaces y’all create are also an important part of what you’re doing.

BM: I just like to party [laughs]. I’ve done the raves, Harajuku nights, goth nights. I want to do a Hi-NRG night, a cumbia night.

JJ: Obviously, Frutas is focused on people. But it’s also a living document and an archive of L.A. You’ve shot in the Callejones. You’ve shot in Koreatown. At mom-and-pop 99 cents stores.

BM: The backgrounds are very intentional in comparison to the models. I want to make sure that the colors are complementary — either the same colors, or they’re bouncing off of each other or they’re really representative of L.A. or that neighborhood. I love L.A. both for the community, but also just the city itself. Frutas is an homage to Los Angeles. I really want it to feel like this is our playground, like this is our world. We’re taking up space, we walk these streets. This is our community. This is our turf. We live here, we contribute here, we love here.

JJ: You’ve also done issues in Long Beach and Mexico City.

BM: I’m trying to span out. My next issue is going to be in South Central. And then I want to do one in the Valley. And one in the I.E. I would potentially like to do one in Tijuana. New York would be cool. Japan would be sick.

JJ: What was it like shooting in Mexico City?

BM: Mexico City, I love it. It’s sick. But the last time was really sad [because of gentrification]. I felt a little weird shooting there. I hired someone to help me cast locally, I paid everyone and I did my best for being an American coming in — obviously, I’m of Mexican descent, but I’m still American. I wanted to be respectful. It was cool. And everyone was f—ing awesome. I just don’t want to contribute to that. I don’t want people to think it’s cool to move to Mexico City. That’s why I feel a little apprehensive. I do want to highlight it and be like, “Look, there’s sick style here,” but it doesn’t mean you should move there. Stay in the States [laughs]. In the South Central issue, I’m going to try to incorporate that: Y’all can look, but don’t move there.

JJ: If Frutas could talk, what do you think it would say about L.A.?

BM: We’re sick as f—.

JJ: Is there anything else you want to add?

BM: I did want to touch on Veteranas and Rucas. When I saw Lupe [Rosales] doing that, I thought it was so important. And realizing later that Frutas could be an archival thing, I did see a tie there. She was showing ravers, party crews — you could not look up party crews on the internet before Veteranas and Rucas. I grew up with that. My mom and dad were into Hi-NRG, my tío was into techno and hard house. Seeing their fliers, their pictures, their little group photos … [Veteranas and Rucas] gave me a connection because I felt [like I was] sticking out in that regard and unable to resonate with other Mexican American kids [with more traditional backgrounds] my age. Not until later did I start meeting people like, “ I had a brother in a party crew. My parents were in a party crew.”

JJ: What’s so cool about the work of archiving certain aspects of subcultures, or cultures in general, is that it’s a connector. It really does give you context.

BM: That inspired me. Like, “Oh, this is important.” We should be documenting this and archiving this because we’re contributing to these really cool flourishing communities, and people don’t know about it. And if you don’t document it, it’s gonna be lost to nothingness until someone comes along to gather all that and prove that it existed.