There’s a moment in 2002’s “The Hot Chick” that I return to often: Adam Sandler’s Mambuza Bongo Guy hanging out in the antique store, showing Anna Faris all the neat stuff on sale. There’s a little wooden flute, a model of the prison on Robben Island that held Nelson Mandela (the film’s humor has aged like unrefrigerated milk). And with each item, Bongo Guy points out to his customer that it has an especially useful compartment, punctuating each demonstration with the phrase “You can put your weed in there.”

It’s a really silly thing to have bouncing around in your head for more than a decade, but it’s a line that comes back to me every time I come across a garment that has an especially clever pocket or zipper or flapped-over stash spot. And as Goodfight creative director Julia Chu was showing me the Terminal shirt, which is an oxford-cloth button-down with a oxford-cloth fishing vest sewn on top, it happened again. When she dug her hand into the space between the vest and the shirt, revealing four gargantuan pockets in addition to the gear-sized ones on the front and back, Adam Sandler’s voice floated into my head telling me exactly what I could do with it.

Daniel DeSure’s brand and the artist community behind it are pushing the possibilities of communicating through graphics on clothes.

Goodfight’s bread-and-butter remains a species of chill, G.O.R.P.-y, arty garment — one buyer, co-brand director said, told them the brand was like a cross between Comme des Garçons and Levi’s. A new Vans collab is a Mary Jane with an orchid attached. But they also do custom tailoring (Goodfight outfitted “Minari” director Lee Isaac Chung at the Oscars a couple of years back). Watchful pocketing is a mindset they bring there too: “It’s really about making people feel really special,” says Chu. “It’s a conversation about ‘How do you want to feel?’ You can bring hand sanitizer or you can bring a comb. What can we put in it to make you feel like the best version of yourself?”

The brand was founded in 2017 by husband-and-wife brand directors Lin and Christina Chou, Chu and designer Calvin Nguyen. All but Chou met working at Opening Ceremony in Los Angeles in 2008. (Chou, who married Lin in 2014, is also a Hollywood agent for clients including Lee Isaac Chung and Steven Yeun. Of the ongoing writers and actors strikes, she says, “The founding premise of Goodfight has always been about process, about what you often don’t see but comes to light later in product, in reputation. I don’t want to make a big comparison to what’s happening and other parts of entertainment, but there are fights right now that are happening to make sure there’s that realignment.”) Then, the three drifted on to other jobs. Lin and Chu became buyers for American Rag Cie, and Nguyen became the in-house designer at American Rag. But they stayed in touch throughout the years, and eventually came together to start making the kind of clothes they weren’t encountering in their travels. The word “functional” came up a lot while we spoke.

“I bring stuff we create on camping trips, I swim and jump lakes with it,” Nguyen says. “But we also do everyday tasks like production runs over picking up samples; the things have to be very comfortable. They’d have to work in the weather where we are. And they have to last. When we’re picking up bolts of fabric, or Julia’s moving things downstairs, the stuff can’t just rip. We need to make things last in people’s closets.”

Melvin Backman: The label is called Goodfight as a nod to the struggle of putting together well-crafted things, right?

Caleb Lin: Honestly, there wasn’t any one thing that necessarily spurred it. I think we all are the kind of people who walk around with a little chip on our shoulder. There are things we stand for, things we believe in, that we feel are worth struggling a little bit harder for. Whether it’s the way we produce things or where we get our fabric or who we work with — it has a lot to do with process. Things that we’re committed to as a brand that are important to us, that make it worth it for us to even do this.

MB: What’s a bad fight?

CL: A lot of our friends are asking us that too.

MB: Is it, like, putting a lot of energy into something that has you saying, “Why are you doing that? You don’t need to do that. You could be doing this other great stuff instead?”

Christina Chou: [laughs] Like a Republican campaign? Totally.

CL: Not to jump into any kind of partisan politics or anything like that, but to us the fight is not about an aesthetic. It’s about the way we treat people. At the end of the day, that’s what it’s about. If we look at another organization, and we look at the way they pay people or the way that they manage their relationships and different things like that — that’s more of what we look at than, Oh, there’s another company or brand that does something aesthetically that’s not to our liking. There’s so many different brands. Everybody has a different path. What has been important for us is how we treat people that we work with.

MB: Where did y’all meet?

Julia Chu: We initially met working at Opening Ceremony in L.A. R.I.P.! That was home away from home for us.

The Taiwanese American artist’s designs are an antidote for a textile industry status quo that just talks the talk.

CL: I think it was more than 13 or 14 years ago. We met, initially, at the shop on La Cienega.

JC: I feel like every neighborhood, every part of the city has its beloved shop that people really root for. For Mid-City, Opening Ceremony was so new and exciting and doing something that had not happened in L.A. for a while. So I think that’s probably the pool that attracted us, right to OC. And it’s different — everyone drives. So you have to really want to be there. Destination shopping, that’s what L.A. is built on. So people rally around and are very loyal to their shops.

MB: Can you talk about the Goodfight creative process?

Calvin Nguyen: Most of the time, I’ll pick and choose themes or stories to play off of when we start creating a new collection. We talk about what we really like about it, what we don’t, how we can change things here and there. But the process is re-evolving throughout the whole design process.

MB: So much of Goodfight clothing is about simple forms with really interesting details. It’s the sort of thing where maybe it’s not obvious to everybody, but it’s noticeable to people who notice that kind of stuff. Do you all ever have weird, silly fights? Like, “No, no, no! This button needs to be 2 inches away from the other one, not 3”?

JC: [laughs] It’s probably what we spend the most time fighting about. It’s true. Since we started, we’ve always loved clothes, we’ve loved selling clothes, we love touching clothes and experiencing clothes. The clothes that excite us individually, or together as a group, are when people infuse these really interesting personal details [into the clothes]. We’ve always made clothes for people who are kind of nerdy, like us. We’re very specific — Calvin is really specific about the way a sleeve is going to drape, the length of a short sleeve, the opening of a collar.

All of us have our individual preferences. [laughs] So all of our design meetings are talking about very, very mundane details: What to call the name of something. What color to settle on. The name of the color that we want to give on our website. Every button size. Every button finish. The type of thread — all that stuff we end up getting into debates about.

MB: Since y’all work so closely together, how do you come to a consensus or final decision on different details and approaches?

CL: We all have different goals. All of us wear multiple hats. Christina manages our business strategy, makes sure that we are still running as a brand. I run more operations. Julia still works as a stylist — she also works very closely with Calvin on design. Calvin’s expertise is in the fabrication of the really strange creative designs that you see. One of our most popular pants is the Train Track pant — that’s one pant that we brought back for our five-year anniversary collection with Dover Street. The zippers run down the front with lined mesh pockets on the inside to hold paint cans and things like that. Those kinds of things come from his brain. But ultimately, I think we all bring in our different kinds of expertise.

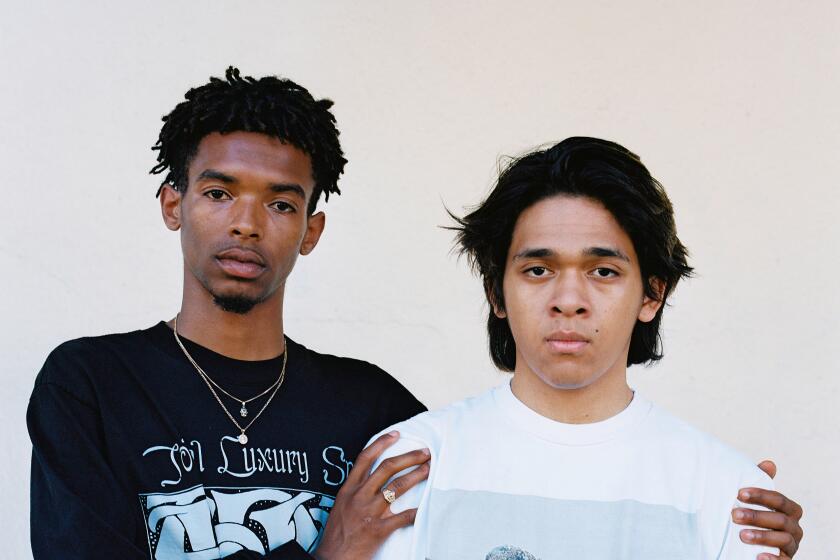

Caleb (top left) wears New Era Kansas City Chiefs cap; Goodfight Turbo Flow shirt; Goodfight Harvest Tee by Justine Lin and Reflection Trousers; Chisos No. 6 Roper Boots from Austin, Texas; Good Art Hlywd for Goodfight jewelry; vintage bandana from Japan; Julia (top right) wears Vintage, Susumi Studio, Soft Good Studio necklaces; Goodfight Western Shirt Textured Weave and Gilman Denim Trousers Diamond Stitch Indigo; Vault by Vans x Goodfight OG Style 93 LX

Christina (bottom left) wears Junya Watanabe x Comme des Garçons shirt; Simone Rocha skirt; Vault by Vans x Goodfight OG Style 93 LX; Calvin (bottom right)wears New Era cap; Goodfight Studio Tee and Grocery Getter Shorts; Good Art Hlywd for Goodfight necklace; Nike socks; Solovair Single Monk shoes (June Kim / For The Times)

MB: I wanted to ask about the Milky Way shirt that was in your latest lookbook. It’s a long-sleeve, short-sleeve, crop, non-crop hybrid thing. How does that work?

CN: I think it originally came from finding a fabric that’s very lightweight but wanting really badly to use it on a menswear piece. It was just simply saying, “Hey, if we double up this fabric, it will cover up any kind of insecurities that a man might have about wearing it.” [We] put it together in a way that’s a little different and new. A double layer to share more truth and flow in the fabric. Show how the fabric can really react to wind and movement.

JC: A couple seasons ago, we had a shirt where the print across the chest was foods and desserts that we grew up eating. We had that custom-printed on a shirt that had two layers, like a tablecloth on top of a table. That’s where the original “double” concept came up. We’ve always played with a layering concept in a lot of our pieces to dwell on but also to spark a little bit of fun in the illusion. Where you’re like, “Is that one hem? Is that two? What’s happening in your shirt?”

MB: And what makes the pattern wrong? Like, what’s it supposed to do, and then what’s it doing instead of that?

Bespoke clothing is not an everyday occurrence in L.A. But for Erik Kim and Paul Um, creating a one-of-one piece is a religious experience.

CL: There are ways to force the fabric to do certain things. There are ways to let it fall naturally. And typically you want to create a natural fall. We’ll pull an anchor point to a specific area in the seam that will create a different shape that you don’t traditionally see. We like those things — we like to break the rules when the rules are there and create new rules.

MB: Is there anything else coming up that y’all are excited about?

CL: We also have our first collaboration shoe coming out at the end of this month with Vans.

CC: It is actually a T-strap Mary Jane. Suede upper, silver buckle and this orchid 3-D-printed shoe clip.

CN: The orchid is based off of Singapore’s national flower.

CL: Calvin went to high school in Singapore.

MB: How’d you end up in Singapore?

CN: It was just because of my dad’s job at the time. So they had him moved from New Orleans to Singapore. I was born in New Orleans, spent my formative years in Singapore and then went to college and everything in California.

MB: My dad spent a lot of time working in Taiwan when I was growing up. I only visited once, but I get the long-distance thing.

CL: Ah, cool. Christina, Julia and I are Taiwanese. It’s the kind of third-culture element of our identities. It’s something that we’re not too overt about, but it’s always something that we’ve blended into. If you talk about the idea of identity, even identity with people who are from that island, it’s very complicated. And it’s very, very challenging, because of history, because of the current political situation, a lot of different factors. But that’s also relevant toward who we are too. Our parents are Asian. But at the same time, we are Western. Christina is from the South Side of Chicago. I’m from New York, Julia is from Los Angeles. Calvin’s parents escaped the Vietnam War, coming to the U.S., and grew up in the Midwest with families there. It’s all very complicated but also very beautiful and special. That’s what’s always been really exciting for us, and that definitely served as an inspiration for us as a brand.

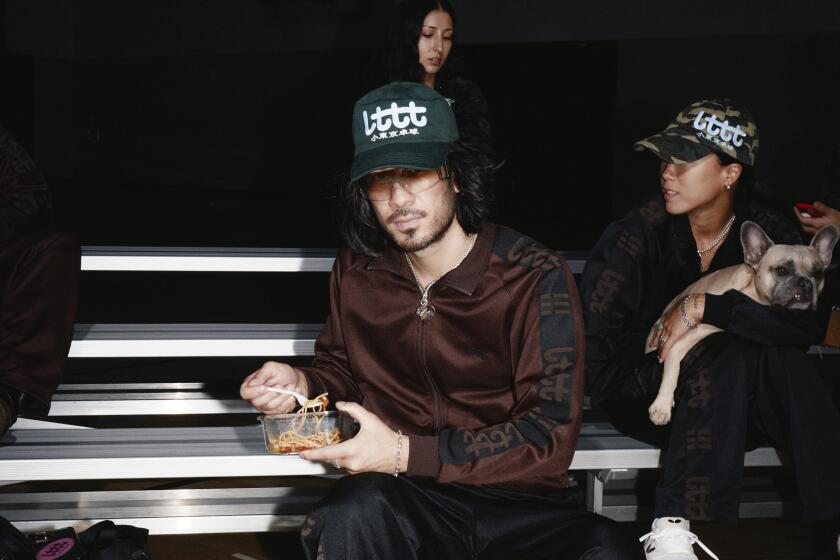

Chances are you have crossed paths with LTTT somewhere. The fashion brand by Jiro Maetsu is an “unspoken but blatant community” that has exploded from L.A. to the world.

Very early on, we tried to shy away from being known as “Asian American designers.” We don’t want people to buy Goodfight because we’re Asian American or just because of our cultural identity; we would hope that the product will stand by itself. I think that’s a very Asian American idea too — that we just want to be judged by the merit of our work. But at the same time, we are aware and sensitive to the fact that it does have meaning for people. Everything that we buy has some kind of nostalgic element or some reason for why it’s important to us. It is a constant negotiation for us. We’re not hiding who we are — we are very overt about the stories that we tell — but at the same time we’re not a cultural company or something like that. We just want to make a really beautiful suit, and it’s just a beautiful suit.

MB: What are people doing with their Goodfight clothes?

CL: We had a few pieces that got really popular because Justin [Bieber] wore them [during Drake’s verse in DJ Khaled’s “Popstar” video]. And the next week, we saw a kid coming down the street in the tabletop shirt that Julia was talking about, which is an ode to some of the Southeast Asian cuisine that Calvin used to eat growing up. He was skateboarding down the street, this young kid just sweating in this $480 shirt. No. 1, we’re like, how did you afford that? No. 2, there was a giant sweat stain on the shirt and we’re just like, “Yo, that’s amazing.” We want people to live in the clothing and have fun in it and mess it up. We don’t want to only see our clothes in cool street snaps or on the red carpet. We love seeing it in the wild.

JC: There’s always a nod to function. We want to make clothes that anyone can wear. And in an ideal world they’re going to find the mysterious pocket that holds your phone also holds a notebook and is just a highly functional piece. Calvin pulls in a lot of really interesting things from fishing gear, paintball gear, hiking gear, stuff that is not fashion. I don’t come from that background, so it’s always fun to think about how we can put a new pocket in. Maybe I don’t need a pocket for my fishing hooks, but I can certainly find a new use for it.

MB: Like with the Terminal shirt?

CN: I was really inspired by fishing gear and didn’t see the thing that I wanted out in the market, which is something that’s less technical, maybe easier to wear, subtler. All the pockets actually fit in fishing gear. We actually brought all the stuff that I have, and we measured everything.

CL: He actually mapped out the vest with actual fishing gear to create the pockets on the vest. They’re not arbitrary pockets. He took all the gear that he would want to carry on a typical day out on the lake, and he created the pockets accordingly. And then I think the Goodfight element is that the vest is actually built into the oxford in one piece. We did a two-piece version, which people could get as they gravitated toward the weird shirt that had the vest built in.

MB: It seems like a lot of your sensibility could be boiled down to the placement of good pockets.

CL: A good pocket can change the game.

Melvin Backman is a writer and editor based in New York.

Lettering by Jake Garcia / For The Times