Rio Uribe tries not to let himself slip into the honeyed molasses of nostalgia. Not right now — he’s got work to do, a 10-year anniversary fashion show to plan. And there’s nothing productive about reminiscing. But every once in a while, the sheen of his bygone years glimmer, beckoning him back to study them like a roadmap.

Uribe was a teenager growing up in the San Fernando Valley when he began documenting every look he wore to school in consuming detail. Let’s say it was Aug. 10, 2000: There was likely a scoop of Murray’s hair gel in his curls. His yellow button-down Sean John shirt was undoubtedly worn crisp, matching the yellow stitching on his indigo Levi’s (that were cuffed up exactly two inches). There were probably Lugz on his feet too. Uribe found the book where he kept these written entries in a box of his old stuff in 2019, when he moved himself and his brand Gypsy Sport back home to L.A. after being in New York his entire career — a time and place where his dream of “becoming an amazing designer one day” was realized.

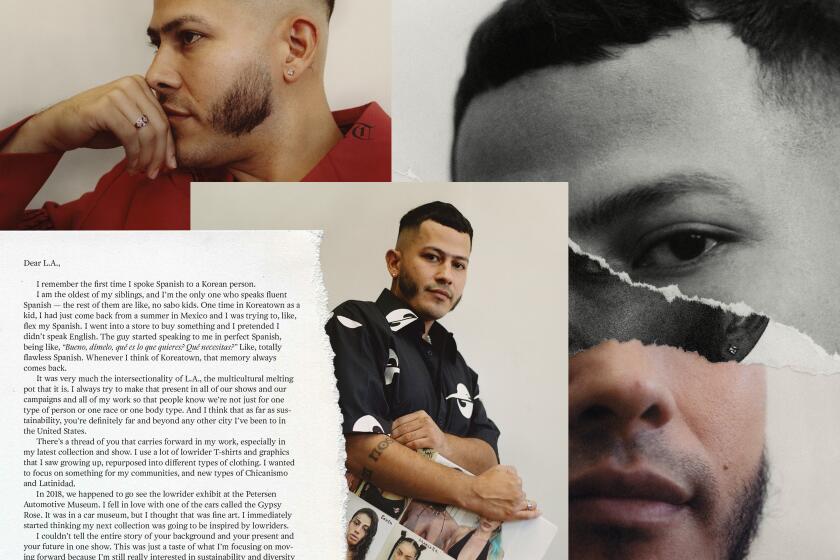

This year, Gypsy Sport celebrates a decade. Uribe’s fashion label is a tween. And while the last 10 years have taken the brand through its share of growth and change, they have only sharpened the specific Gypsy Sport attitude that’s been there from the jump: Wear your freak flag on your back and ride for your community through your clothes — which over time have refined too, but remain artistic and animated while being rooted in subculture and queerness.

Gypsy Sport designer and creative director Rio Uribe sees a future where eco-friendly won’t be slept on

When it first started, it was about people, about the moment, “a really cool collective of outcasts with talents and skills,” Uribe says. Gypsy Sport castings and fashion shows became — and remain — legendary, cherry picking models from a diversity of sexualities, genders, ethnicities, walks of life. This, over time, dictated its tribe: When you see the “haturn” out in the world (Gypsy Sport’s logo made of two hats on top of each other facing opposite directions to form what looks like a planet), you know it represents the brand’s vision of unity, balance and community. This spirit extended into a Gypsy Sport festival, called GSpot, which became “a sexy party for all body types, all genders,” held in Brooklyn, L.A. and Miami. “People f— with us because they know we’ve been doing this from day one,” Uribe says. “We’re not about exploiting people. We’re about exposing and celebrating them.”

This month, Gypsy Sport returned to New York Fashion Week with a new collection after showing in L.A. for the last two years. With the show, Uribe was once again urged to look back on the thing he created as an artist in his 20s chasing the same sense of purpose he got when he was a teenager logging his looks. It was also Uribe’s last time showing as Gypsy Sport. For years, there have been calls to extinguish the word “gypsy” from fashion and popular culture’s vernacular — a word that is widely considered a slur. At the beginning, Uribe says he chose the name because it represented a global subculture that was “aspirational” to him. “But it doesn’t take away from the fact that some people are hurt by the word and it doesn’t take the power away from the people who are using it as a slur,” he says. “It just doesn’t feel like me today. I’m OK with letting it go.” The 10-year anniversary show closes this chapter on Gypsy Sport, Uribe says. “I’m starting a whole new book.”

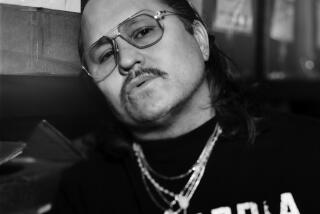

At Civil Coffee in DTLA, Uribe sips a hojicha latte as he dedicates himself to the process of remembering — combing his memory bank for context clues. After high school, he knew two things: that he was going to work in fashion and that he was going to move to New York. He bought the one-way ticket, booked the sublease on Craigslist, took any job he could — which for almost two years consisted of mostly side hustles — before landing a position at Y2K staple Paul Frank, and later Balenciaga, where he worked in the stockroom before climbing his way up to visual merchandiser for the brand’s North American stores. He became friendly with then-creative director Nicolas Ghesquière, met Anna Wintour (whom he would later be on a texting basis with) and flew to Paris. “It was so special,” Uribe says. “I was this young Chicano kid from the Valley randomly in this beautiful atelier in Paris learning about fashion.” He had done what he set out to do. But there was a gnawing.

Since its inception over a decade ago, the brand has steered the conversation about clothes with unmatched inventiveness by continuing to experiment with any given guardrails.

At the time, Uribe was making hats, vests and T-shirts inside his apartment. Creating from his own hands felt important, he says, and he couldn’t break into design in his current position. When he quit Balenciaga, his friends said he was crazy. Not long after, Alastair McKimm (the current editor of i-D) was doing a styling job for DKNY and saw Uribe wearing one of his hats around town — made out of karate belts — and placed an order. Opening Ceremony soon followed.

These were the kinds of moments, Uribe says, “that just make you feel like OK, no matter what, no matter how rich or poor, healthy or sick, ready or not, this is what I’m supposed to be doing. The universe is aligning for me to do these crazy things. But also, having a community and showcasing them in my work is what really also helps to make it happen.” In 2013, Gypsy Sport entered the VFILES Runway competition and won, presenting its first completed collection. “I basically have had a show every season from that point on — sometimes with zero money, and sometimes with great sponsors and backers. It’s been a high-low roller coaster ride.”

Uribe didn’t go to fashion school but was a dedicated student, learning the language of fashion on his own. Which is how, during one of Gypsy Sport’s early fashion shows in Washington Square Park, he was able to spot iconic fashion editor and writer Lynn Yaeger walking home . He invited her to the show, an idea he remembers her calling “outlandish” — to throw a fashion show in one of the busiest parks in the city during fashion week — but she attended anyway. Other big moments included being awarded the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund in 2015 (as of this year, Uribe has joined the CFDA), attending the Met Gala in 2022 wearing one of Gypsy Sport’s many takes on the zoot suit and and being an apprentice for John Galliano.

Early on, the clothes were infused with a delightfully chaotic DIY spirit. They were sustainable both out of principle but also necessity. During his guerilla-style spring 2018 ready-to-wear show at the Place de la République in Paris, models charged down the square in jeans worn as a minidress, a workshirt that was a collage of cut-up button-downs, sports memorabilia being treated like high art. Uribe told Vogue: “Those are my old Levi’s, that’s my Kaepernick jersey and that’s my grandmother’s crochet!” The looks incorporated Gypsy Sport’s classic sportiness, gender-bending and subversive quality, which could also be seen in Uribe’s spring 2020 show, when he sent a model down the runway in full shimmering blue and tangerine body paint, wearing a chain mail halter dress made out of beaded safety pins.

Physical spaces in L.A. have always been sacred. Ashley S.P. and Jennifer Zapata see their concept shop as a vehicle for community and an homage to their friendship.

But something crystallized even further in the design of the clothing when Uribe decided to move back to L.A. His return collection, spring 2021 ready-to-wear, utilized upcycled vintage T-shirts that featured classic L.A. motifs (big rigs, the 15 freeway sign) modeled in glittering L.A. fashion by artists such as Gabriela Ruiz and Mia Carucci. When Uribe was in New York, the struggle was constant — even when he started gaining traction with the brand, he was couch surfing and struggling to make ends meet. Seeing those early collections, he thinks more about his community at the time — a rotating collective of anywhere from eight to 12 people who helped make the brand what it is. But in the clothes, he sees too much inspiration and not enough resources. “A lot of people who liked it related to the savageness of it,” he says.

In L.A., a newfound sense of creativity came from freedom instead of pressure. The work he’s made here has a distinct direction, inspired by different Chicano subcultures while celebrating the brand’s queer identity. His first L.A. show, for Gypsy Sport’s spring 2022 ready-to-wear collection, was held on the roof of the Petersen Automotive Museum and influenced by L.A. car culture. Model Luna Lovebad walked out in a baby pink bubble coat dress featuring motifs that drew on what is maybe the most famous lowrider in the city: the Gypsy Rose, a 1964 Chevy Impala. The collection that followed drew from mall punk aesthetics, showing at the old Amoeba Music building. “Now I feel like I’m finally getting to a place where — because I know what is inspiring me the most — I’m able to transmute that,” Uribe says. Gypsy Sport returned to New York, which he calls a different beast entirely, a changed brand.

Uribe is a triple Scorpio. Death and rebirth are themes he’s familiar with. He’ll be announcing a new name after the show, which during the time of our interview he still hadn’t decided on yet. But for now, it’s time to honor what was. With the show, Uribe is planning a birthday party, retrospective and memorial service all in one for Gypsy Sport.

The collection will be self-referential, he says — commemorating the last 10 years by making new pieces that take inspiration from Gypsy Sport’s past designs. And the show will feature quintessential pieces from the brand, like its SS ’22 Kobe Tribute dress.

Uribe likes to think of drawing on your own memories and experiences as being eco-friendly — part of Gypsy Sport’s ethos from the beginning. To look at a piece and remember where he was, to remember where the brand was and commemorate that? “It’s emotionally sustainable,” Uribe says.

Lettering by Jake Garcia / For The Times