The Other Beating

George Holliday is a rooter, the guy you call when the remains of Sunday dinner have blocked the garbage disposal line or if the toilet’s stopped up again. He shines his Maglite on the dirty jobs few others will take, including the ones that crop up at my house with maddening frequency because of an eccentric plumbing scheme and hardy roots from our pine tree. We got his name and number from a friend, considered ourselves lucky and thought no more about it.

Once, when George was unavailable, we called another rooter.

“I can’t do that, man. You need George.”

“Why?”

“Because he’s the only guy around who carries 200 feet of cable. He’s strong, man. Don’t you know who he is?”

FOR THE RECORD:

Former police chief —Sunday’s West magazine article on George Holliday, the man who videotaped the Rodney King beating, incorrectly spelled Daryl Gates’ first name as Darryl.

“Yeah, he’s a rooter.”

“No—don’t you know who George Holliday is?”

I didn’t, actually, until I rolled the name around in my head for a while. Then I realized: George Holliday was the Rodney King videographer. Awakened by sirens just after midnight on March 3, 1991—15 years ago next month—he grabbed his Sony Handycam, stepped out onto the balcony of his Lake View Terrace apartment and captured King’s beating by four LAPD officers. The video triggered a media sensation and, after the acquittal of the officers, helped ignite the riots that led to 54 deaths, 2,383 injuries, hundreds of destroyed buildings and more than 12,000 arrests.

Back then, George was married and a manager at a big plumbing and rooting company. Now he’s twice divorced, self-employed and scraping by. He might have been better off had he stayed in bed that night.

After he gave the eight-minute video to KTLA, his name was trumpeted in the newspapers and plastered across television screens and repeated on the radio. (The episode has eerie echoes today with the recent police shooting of a San Bernardino man, caught on tape by a used-car salesman, Jose Luis Valdes.) George received a couple of death threats in the mail—”Be careful when you start your car in the morning,” one said; the other was an envelope full of drawings of daggers—and often when people recognized him they’d say: “You’re the guy who caused the riots.”

His first wife left him. “There was a sea of reporters every day,” he recalled, sitting at my kitchen table. “Maria didn’t even want to leave the house.” His second marriage didn’t work out either.

When he adds it up, he doesn’t see that he got much on the positive side: a few thousand dollars (he wouldn’t be specific) from licensing the video to filmmakers, including Spike Lee for “Malcolm X”; plaques from the L.A. County Board of Supervisors and the LAPD; and his name on a Trivial Pursuit card—misspelled as “Halliday.” When the LAPD honored him, he met the now-infamous then-chief of police. “Darryl Gates pulled me aside and told me, ‘If you ever have any problems, here’s my personal direct number.’ ” George never called.

He has had problems, though it’s hard to say how many of them have to do with his decision to make the video public. When we talked about it, he didn’t spread the blame around. But he didn’t have kind words for the media. He may have pioneered “citizen journalism,” but he feels that he was swallowed up and spit out by CNN and the like, which, he said, gave him little credit and no compensation for his contribution to history. “I don’t watch the news or read the papers anymore.”

He’s gentler with the cops. As horrified as he was when he saw the beating through the Handycam viewfinder, he felt uncomfortable about the impact his video had on the image of the LAPD. “I filmed this tape that makes the police look bad,” he said, thinking about his grandfather, who was a bobby in London. “But every time a policeman has recognized me, they tell me I did the right thing.”

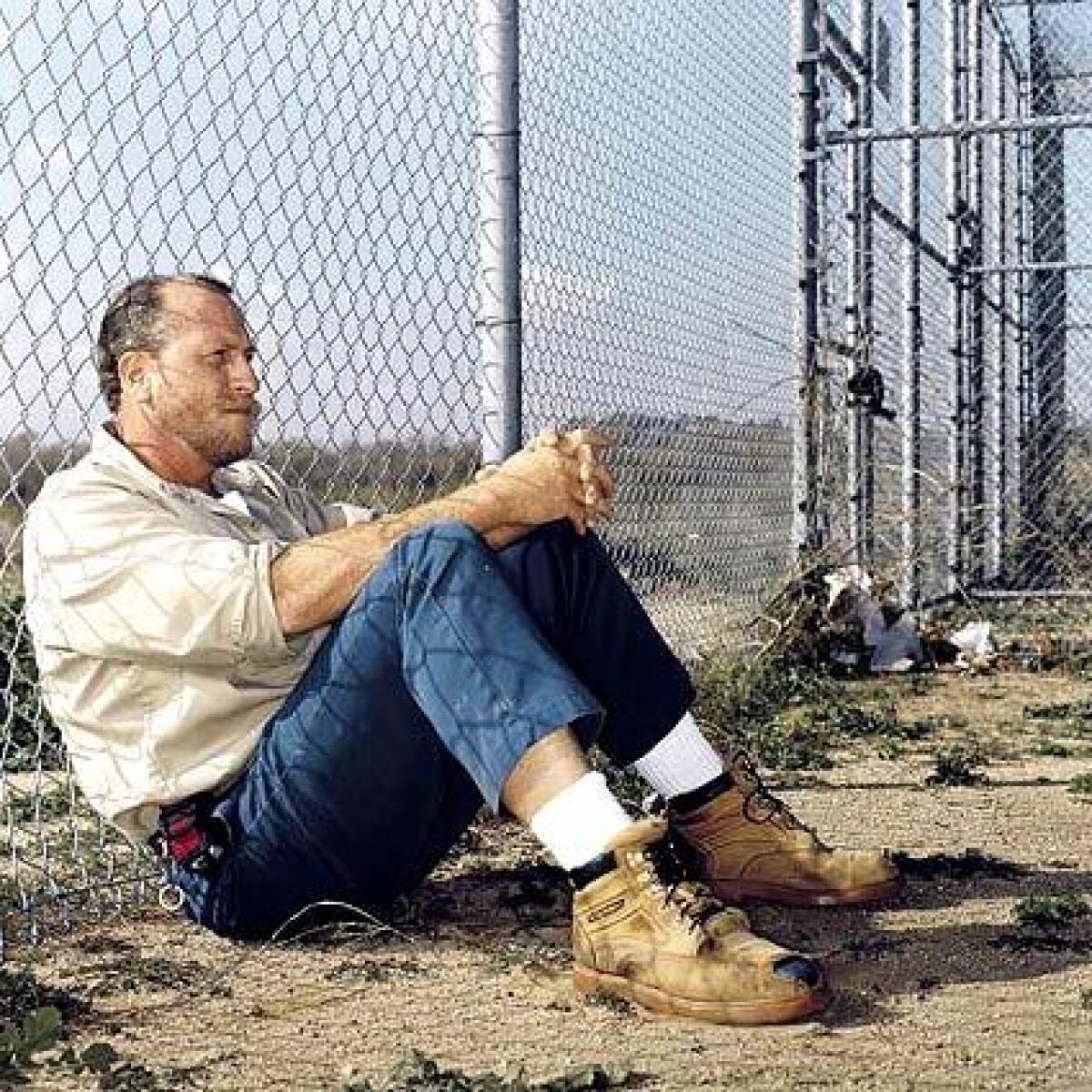

At 45, George is a solidly built 6-foot-1, 225 pounds with bulging muscles from years of carrying rooting machines and reels of cable that weigh hundreds of pounds. He looks like a lion, with reddish hair and a near-handlebar mustache. He wears steel-toed boots and drives a van with pipes on the roof and a “One nation under God” magnet on the back. He and his 9-year-old son live in a rented 1,000-square-foot guest cottage in the Valley.

Their telephone number is unlisted. So is George’s business number. He takes jobs only by referral; he doesn’t advertise. He tells me that it’s not really that he’s afraid of people recognizing his name. “I like not being bothered.”

He’s rarely short of work. He earns enough to send his son to a private Christian school, and saved enough to spend last Christmas in Argentina, where he grew up and lived until 1980. He was able to introduce his son to the child’s grandmother, aunts and cousins for the first time.

This year, George will become a U.S. citizen. And he will do something else momentous: He will put a DVD of the video, all eight minutes, on the market. It was the idea of a childhood friend, who is in the television production business. Their plan is to sell the DVD through the friend’s website until they find a distributor. They hope the DVD will be of use to educators and students who don’t know anything about the King incident.

The DVD will have an interview with George, who’s still astounded by the incident. “I was thinking, ‘What did the guy do to deserve this beating?’ I came from a different culture, where people would get disappeared with no due process. Police would pick people up on suspicion. I didn’t expect this in the U.S.”