Muhammad Ali, the brash and ebullient heavyweight boxer whose brilliance in the ring and bravado outside it made his face one of the most recognizable in the world, has died.

Opinion: Don’t remember Muhammad Ali as a sanctified sports hero. He was a powerful, dangerous political force

Muhammad Ali‘s saga is without parallel: the champion boxer who was the most famous draft resister in history; a man whose phone was bugged by the Johnson and Nixon administrations yet who later was invited to the White House of Gerald Ford; a prodigal son whom his hometown city council in Louisville, Ky., condemned, but who a few years later had a main street renamed in his honor and today has a museum that bears his name.

Read More— Dave Zirin

At hospital where Muhammad Ali died, tributes for an idol who showed ‘why telling the truth matters’

Lynn Boyd Jr., 60, remembers hearing his mother yell, “Cassius Clay is on Wide World of Sports!”

He was 11 years old and came sprinting with his siblings into the house, as was routine any time his loud, brash idol appeared on TV.

Boyd returned Saturday to stand in front of the hospital where Muhammad Ali died, and for one last time, feel close to the most influential sports figure of his lifetime.

President Obama offers condolences to Muhammad Ali’s widow

President Obama called Muhammad Ali’s widow Saturday afternoon to offer the first family’s “deepest condolences” at the former heavyweight champion’s passing, White House deputy press secretary Jennifer Friedman said.

Obama told Yolanda “Lonnie” Williams how fortunate he and First Lady Michelle Obama felt to have met Ali and said the “outpouring of love since his death is a true testament to his remarkable life,” Friedman said.

Obama also told Williams how special it was to have witnessed “The Champ” change the arc of history, Friedman said.

Muhammad Ali talks man out of jumping off a building in Los Angeles

Muhammad Ali happened to be in the area when a distraught man was threatening to jump from the ninth floor of a Miracle Mile building in January 1981.

Ali died of septic shock, his funeral will be on Friday, family says

A family spokesman said Saturday that Muhammad Ali died of septic shock “due to unspecified natural causes.”

The spokesman said Ali died Friday at 9:10 p.m., spending the last hour of his life surrounded by his family. He was initially hospitalized in the Phoenix area on Monday.

The funeral for the three-time heavyweight champion is scheduled for Friday afternoon at the KFC Yum! Center in Louisville, Ky.

The spokesman said Ali was a citizen of the world and he wanted people of all walks of life to be able to attend his funeral. The service will be translated and streamed on the Internet.

Lance Pugmire narrates Ali’s incredible career

Part 1: Ali’s biggest fights

Los Angeles Times writer Lance Pugmire describes boxing great Muhammad Ali’s early years and breaks down his most significant bouts.

Part 2: Ali’s years as an activist

Los Angeles Times writer Lance Pugmire retraces boxer Muhammad Ali’s conversion to Islam and his years as an activst.

Part 3: Ali’s final years

Los Angeles Times writer Lance Pugmire reviews boxing great Muhammad Ali’s later years in the sport and his impact on the world.

More on the greatest from a friend and journalist

The people.

With Muhammad Ali, it was always the people.

It didn’t matter whether they were rich or poor, black or white, celebrity-famous, blue-collar weary or welfare poor. It didn’t matter what language they spoke, what God they worshiped, what gender they were. Well, in this last group I’d have to say that the ladies had a little edge.

Warriors for a cure

Ali, the poet supreme

Last night I had a dream, When I got to Africa,

I had one hell of a rumble.

I had to beat Tarzan’s behind first,

For claiming to be King of the Jungle.

For this fight, I’ve rassled with alligators,

I’ve tussled with a whale.

I done handcuffed lightning

And throw thunder in jail.

You know I’m bad.

just last week, I murdered a rock,

Injured a stone, Hospitalized a brick.

I’m so mean, I make medicine sick.

I’m so fast, man,

I can run through a hurricane and don’t get wet.

When George Foreman meets me,

He’ll pay his debt.

I can drown the drink of water, and kill a dead tree.

Wait till you see Muhammad Ali.

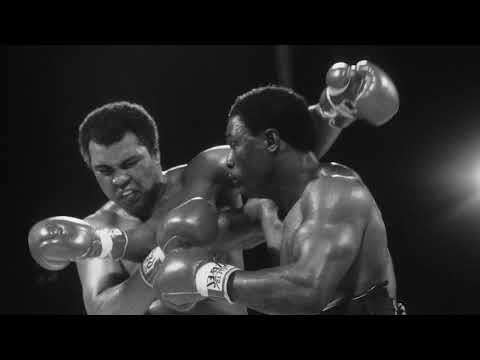

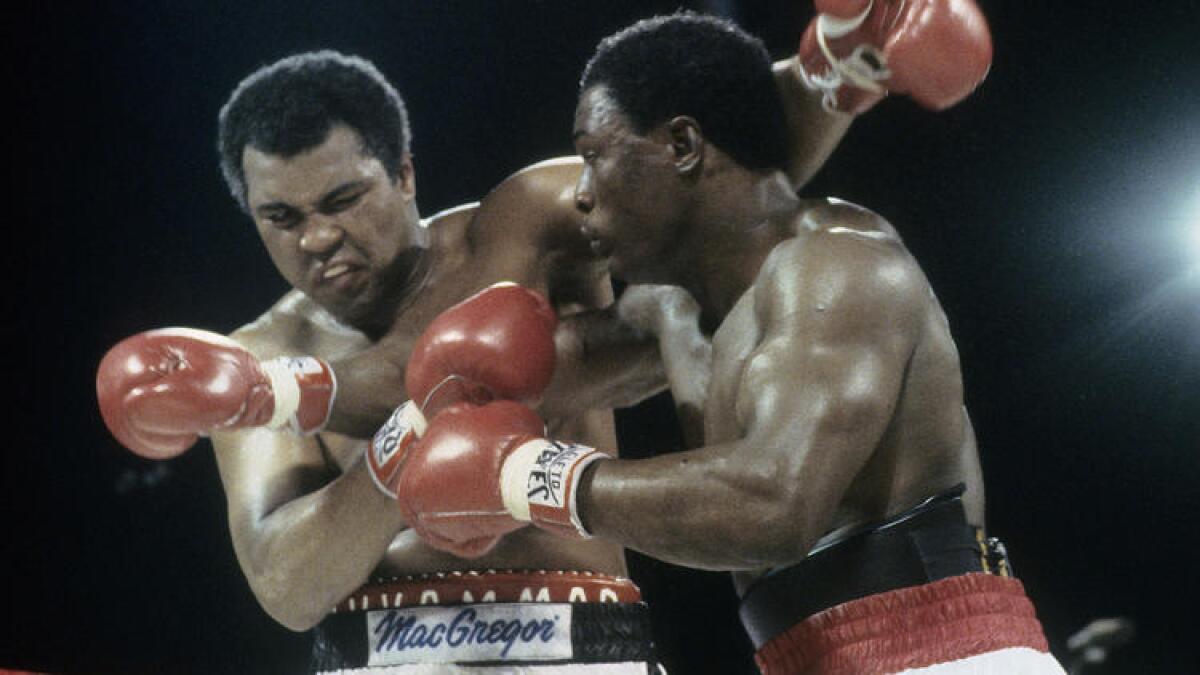

Ali’s ‘Thrilla in Manila’ against Frazier stands the test of time

A bright morning sun typically symbolizes the birth of a new day, the start of something potentially magnificent.

In October 1975, after Muhammad Ali closed his historic trilogy with Joe Frazier in a superior battle that some rank as boxing’s ultimate prizefight, co-promoter Bob Arum recalls exiting the Araneta Coliseum in Manila to burning heat.

“Like something had died,” Arum said.

L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti remembers Ali’s ‘peerless legacy’

“Muhammad Ali gave us incredible skill as a fighter, an incomparable gift for words and a peerless legacy as a sports and cultural icon. He also modeled the extraordinary power of self-determination — inspiring millions to treasure their humanity, claim their dignity and give all they have to the global causes of peace, justice and equality.

— Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti

Op-ed: Muhammad Ali was a powerful, dangerous political force

Cassius Clay chose to be Muhammad Ali and do something different with his voice. He used it to speak out from a hyper-exalted sports platform to change the world. He joined the Nation of Islam in frustration with the pace and demands of the civil rights movement. He was willing to go to jail in opposition to the war in Vietnam. But one has to hear the voice, and read the words, to understand what exactly made it so dangerous and, by extension, made it all matter.

Obama: ‘Muhammad Ali shook up the world. And the world is better for it.’

Statement from President Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama on the passing of Muhammad Ali:

Muhammad Ali was The Greatest. Period. If you just asked him, he’d tell you. He’d tell you he was the double greatest; that he’d “handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder into jail.”

But what made The Champ the greatest – what truly separated him from everyone else – is that everyone else would tell you pretty much the same thing.

Like everyone else on the planet, Michelle and I mourn his passing. But we’re also grateful to God for how fortunate we are to have known him, if just for a while; for how fortunate we all are that The Greatest chose to grace our time.

In my private study, just off the Oval Office, I keep a pair of his gloves on display, just under that iconic photograph of him – the young champ, just 22 years old, roaring like a lion over a fallen Sonny Liston. I was too young when it was taken to understand who he was – still Cassius Clay, already an Olympic gold medal winner, yet to set out on a spiritual journey that would lead him to his Muslim faith, exile him at the peak of his power, and set the stage for his return to greatness with a name as familiar to the downtrodden in the slums of Southeast Asia and the villages of Africa as it was to cheering crowds in Madison Square Garden.

“I am America,” he once declared. “I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me – black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own. Get used to me.”

That’s the Ali I came to know as I came of age – not just as skilled a poet on the mic as he was a fighter in the ring, but a man who fought for what was right. A man who fought for us. He stood with King and Mandela; stood up when it was hard; spoke out when others wouldn’t. His fight outside the ring would cost him his title and his public standing. It would earn him enemies on the left and the right, make him reviled, and nearly send him to jail. But Ali stood his ground. And his victory helped us get used to the America we recognize today.

He wasn’t perfect, of course. For all his magic in the ring, he could be careless with his words, and full of contradictions as his faith evolved. But his wonderful, infectious, even innocent spirit ultimately won him more fans than foes – maybe because in him, we hoped to see something of ourselves. Later, as his physical powers ebbed, he became an even more powerful force for peace and reconciliation around the world. We saw a man who said he was so mean he’d make medicine sick reveal a soft spot, visiting children with illness and disability around the world, telling them they, too, could become the greatest. We watched a hero light a torch, and fight his greatest fight of all on the world stage once again; a battle against the disease that ravaged his body, but couldn’t take the spark from his eyes.

Muhammad Ali shook up the world. And the world is better for it. We are all better for it. Michelle and I send our deepest condolences to his family, and we pray that the greatest fighter of them all finally rests in peace.

Float like a butterfly ...

One champ to another: Foreman salutes Ali

Muhammad Ali meets Clint Eastwood

Here’s a look at a meeting of Muhammad Ali and Clint Eastwood on a talk show, dated 1969 and 1970 in YouTube clips.

Asked to compare himself to past boxing greats, Ali says it’s difficult to measure current athletes against their predecessors, adding, “You can’t compare a jet to a prop.”

To expand his point, he talks cowboys, turning to Eastwood and saying:

“They can’t compare Tom Mix and Hopalong Cassidy and these fellows with you. I mean, those fellows had to do a lot of riding and shooting to get your attention. All he’s got to do is to need a shave and put a dark cigarette in his mouth.”

Then watch Clint hit the speed bag.

— Marc Olson

Unknown Chuck Wepner -- to some, ‘The Real Rocky’ -- knocks down Ali in 1975

Muhammad Ali’s 1974 victory over George Foreman to win the heavyweight championship was one of his greatest achievements, but his first defense of that title also became a notable fight, and maybe the inspiration for an Oscar-winning movie.

On March 24, 1975, five months after knocking out Foreman in Zaire, Ali gave a title shot to an unknown, 6-foot 5-inch New Jersey brawler named Chuck Wepner.

A huge underdog, Wepner surprised observers by lasting into the 15th round and even scoring a 9th-round knockdown — though images later showed Wepner had stepped on Ali’s foot.

“That was the high point of my life,” said Wepner, quoted in a cleveland.com article last year. “I was a 40-1 underdog, and I went 15 rounds against Muhammad Ali.”

Many claim that fight was Sylvester Stallone’s inspiration for “Rocky,” which came out the next year and won the Oscar for best picture.

Jeff Feuerzeig, director of the ESPN documentary “The Real Rocky,” said of the Ali-Wepner fight: “It was one of the most heroic underdog stories we’ve ever seen. Without Chuck, there is no ‘Rocky.’ ”

According to ESPN boxing writer Eric Raskin, “In 2003, Wepner sued Stallone for cashing in on his life story and never sharing a dime with ‘the real Rocky.’ Stallone settled with Wepner for an undisclosed amount.”

— Marc Olson

Clintons recall the champ’s ‘blend of beauty and grace’

Muhammad Ali was remembered as a man “full of religious and political convictions” by Bill and Hillary Clinton.

In a statement released early Saturday, the former president said:

“From the day he claimed the Olympic gold medal in 1960, boxing fans across the world knew they were seeing a blend of beauty and grace, speed and strength that may never be matched again.”

Speaking for himself and his wife, Clinton added:

“We watched him grow from the brash self-confidence of youth and success into a manhood full of religious and political convictions that led him to make tough choices and live with the consequences. Along the way we saw him courageous in the ring, inspiring to the young, compassionate to those in need, and strong and good-humored in bearing the burden of his own health challenges.”

Clinton said he was honored to award the former champ the Presidential Citizens Medal in January 2001 at the White House (shown above).

“Our hearts go out to Lonnie, his children, and his entire family.”

— Marc Olson

Ali’s peers react to the death of a legend

Muhammad Ali’s death Friday brought his longtime friend and promoter Bob Arum to recall the former heavyweight champion as “the most transforming figure that I have encountered – for America and the world.”

Ali died at 74 in a Phoenix hospital, where he was moved this week for a respiratory illness, causing him to require life support Friday as family members came to his bedside.

From the archives: Ali’s last hurrah turns into circus with few laughs

Little enough was expected from this evening and little enough was delivered. Muhammad Ali went out to see if he had gotten any younger Friday night and, sure enough, he hadn’t.

Looking all of his 39 years and 48 weeks, he lost a clumsy unanimous decision to the unremarkable Trevor Berbick, though he did manage to finish with his head still on his shoulders.

“I did good,” Ali said later, “for a 40-year-old.”

Read More— Mark Heisler

Saturday’s sports page

A great Ali story

Veteran boxing publicist Bill Caplan worked on two Muhammad Ali fights, including his famed 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle” against then-unbeaten George Foreman.

“He was a great athlete, but the greatest publicity man I’ve ever known. He would do anything you asked [promotional-wise] and would think of a lot of himself,” Caplan said, recalling a scene months before the Foreman fight where the two heavyweights met casually inside an empty Hilton Hotel boardroom in Caracas, Venezuela.

“I was like a fly on the wall for that,” Caplan said. “Ali was doing color on ABC with Howard Cosell. Ali couldn’t be any kinder one-on-one. He gave Foreman advice on how to handle being the champion, like he was a Dutch uncle — couldn’t have been nicer.

“Then we walked outside, where there were a lot of people in the lobby, and Ali said, ‘You see this robot [emulating Foreman’s slow-moving power punches]? You know what I’m going to do to him?’

“You saw the two faces of Ali in one second. George was laughing and laughing. He got it.”

Chris Paul remembers

From outside the hospital in Arizona

The hospital where Muhammad Ali died, Scottsdale Osborn Medical Center, is a nondescript six-story beige building just west of the Scottsdale Stadium, where the San Francisco Giants play spring ball.

A small cluster of people stood near the hospital entrance, guarded on a 102-degree night by a Phoenix police officer in blue shorts.

“He was just a uniter of people,” said Antoinette Smith, 46. “I guess you could call him my first boxing crush. But he did more than that. He didn’t see color; he didn’t see race.”

A Spanish television station did a live shot in which it proclaimed Ali as the premier fighter in the world. When it was over, the anchors sat on nearby benches in their ties and suit jackets, sweating in the heat, while their gear was pulled away by an assistant pulling a red metal wagon.

“I just came to pay respects,” said Marty Stone, who lives near the hospital. “I came as soon as I heard the news. The guy was an icon in the ring and obviously afterwards.”

At the fights in Carson

The Golden Boy and The Greatest

From one champ to another

From the archives: Ali’s legacy is butterfly and bee

Muhammad Ali turned 70 in 2012, and for many of those 70 years, he had us all on the ropes.

To say he is merely a famous boxer is to say the sky is always blue. There are so many sides to him his nickname should be Octagon.

Now, he is revered. Passage of time softens and endears. He is ill, and has been since 1984, when he first received a diagnosis of Parkinson’s. That was just three years after his final fight, when he made one last, mostly pathetic, effort to convince the world he was still “the Greatest.”

Read More— Bill Dwyre

Love from the Phillipines

Highlights of Ali’s career

1964

Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, stunned the boxing world in February by upsetting seemingly invincible champion Sonny Liston. At 22, Clay was the youngest boxer to take a title from a reigning heavyweight champion.

Shortly after, he announced that he had joined the Nation of Islam and had changed his name to Muhammad Ali. Ali famously said “Cassius Clay is my slave name.”

1965

In the Ali-Liston rematch in May, Ali won a controversial fight with a first-round knockout in what was deemed a “phantom punch.”

Later that year, Ali fought Floyd Patterson, a former heavyweight champion. Ali believed Patterson had made disparaging remarks about his religion, and many felt Ali intentionally prolonged the lopsided fight before stopping Patterson with a a 12-round technical knockout. Ali had called Patterson a “white man’s champion.”

Ali spent his time outside the ring in the ‘pursuit of peace’

Muhammad Ali served as a “messenger of peace” for the United Nations, an organization he first addressed in 1978 when he spoke against apartheid.

The U.N. tweeted this picture tonight of Ali with then-U.N. secretary-general Kofi Annan in 1998. Ali, the organization said, had an ability to bring together people from all races “by preaching ‘healing’ to everyone irrespective of race, religion or age.”

Relive the epic Ali-Frazier fight from 1971

ROUND ONE

Ali started talking to Frazier when the referee gave them instructions. Frazier talked right back at him.

Ali prayed in his corner before the opening bell.

Frazier moved right in and missed with a left to the body. Ali connected with a long left and right to the head and then with a left to the body. Ali sent over a left hook that was blocked. Frazier moved in and was hit again by a short left and right to the head. Frazier dug a solid left to the body.

Read More— Los Angeles Times staff

For a kid from Louisville, there was no one like Muhammad Ali

The static-streaked words tumbling out of the old transistor radio turned the tiny bedroom into a raucous arena.

It was a Monday night in March 1971, my hometown hero was fighting for the heavyweight championship of the world, and I had a ringside seat.

While Muhammad Ali slugged it out with Joe Frazier at Madison Square Garden, I was a 12-year-old kid battling sheets and pillows from the edge of my bed in a modest neighborhood in the east end of Louisville, Ky.

Muhammad Ali was the greatest, but his greatest fights took a lot out of him

We never really knew Muhammad Ali, because, in his heyday, he never stopped talking long enough to let us. Most likely, that was not by chance.

In life, he was “the greatest.” He told us that for so long that we eventually just shrugged and accepted it. In death, and with the benefit of quiet reflection, a more accurate label would be “the most complicated.”

To say Ali, who passed Friday night at a hospital in Phoenix, was a boxer is to say John Wooden was a basketball coach. There is so much more.

Read More— Bill Dwyre

From Ali’s official account

Muhammad Ali dies at 74; boxing champion became worldwide celebrity

After defeating Sonny Liston in 1964, an ecstatic Muhammad Ali declared: “I shocked the world.”

Thrusting his arms into the air, he treated the victory as if it had been a knockout. Never mind that Liston denied him that honor by refusing to step into the ring for the seventh round. Ali’s win gave America a first glimpse of the young man who for the next 50 years would never stop shocking the world.

Ali, the brash and ebullient heavyweight boxer whose brilliance in the ring and bravado outside it made his face one of the most recognizable in the world, has died, according to a statement from his family. He was 74. Ali had suffered from Parkinson’s syndrome for many years.