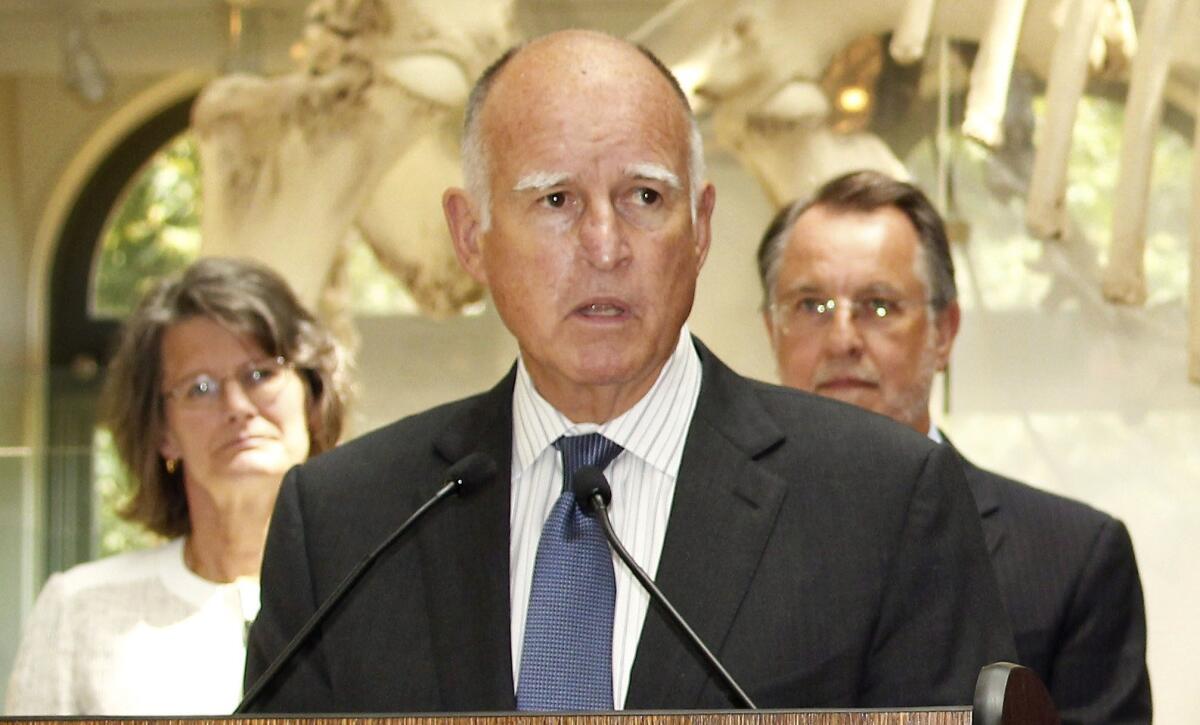

Meet Jerry Brown’s team of science advisors

With Jerry Brown in charge, the governor's office can seem more like a free-wheeling, nonstop conversation than a formal administration, and it's no different when it comes to climate change. Brown regularly turns to a collection of California scientists for help developing new policies, rallying support for fighting global warming and even responding to comments made by Sen. Ted Cruz on a late-night talk show. Sometimes he just calls his team with whatever question is on the top of his mind.

Brown was joined by several of his scientist confidantes at an event in June. Learn more about them by clicking the image.

Some of the scientists are pictured with the governor in June -- click the links below to learn about their roles.

Gov. Jerry Brown with several scientists, including Mary Nichols, chair of the California Air Resources Board, far left, and Christiana Figueres, the top United Nations official on climate change, second from left, at the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles in June. (Samer Momani / Caltrans)

Veerabhadran Ramanathan Ben Santer Elizabeth Hadly & Anthony Barnosky William Collins Dan CayanVeerabhadran Ramanathan | Ben Santer | Elizabeth Hadly and Anthony Barnosky | William Collins | Dan Cayan

SIGN UP for our free Essential Politics newsletter >>

Veerabhadran Ramanathan, Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego

UC San Diego atmospheric scientist Veerabhadran Ramanathan briefly discussed climate change with Pope Francis at the Vatican in May 2014.

Veerabhadran Ramanathan briefly discussed climate change with Pope Francis at the Vatican in May 2014. (UC San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

Known as "Ram," the veteran scientist has been credited by Brown for opening his eyes to the problem and opportunities of short-lived climate pollutants, such as diesel engine exhaust. Not only are such emissions considered especially harmful, but reducing them could also improve people's health, an attractive dual benefit. When Ramanathan had his first meeting with the governor several months ago, he prepared his usual explanation about the dangers of climate change."It became apparent he knew all that," Ramanathan recalled. Instead, Brown asked, "Tell me what I can do next." Ramanathan has since become an admirer of the governor, who continues to consult him for advice.

Shortly before the governor met with the prime minister of India, he asked for some of Ramanathan's research. Then Brown surprised by calling with questions. "I didn't think he would read it," Ramanathan said. During a recent meeting in Sacramento, the governor drilled Ramanathan and another scientist about the challenges of methane emissions and electricity currents. "If I can answer 80% of his questions, I feel very happy," Ramanathan said. He joked, "l'm so glad I'm not working for him."

An atmospheric scientist, Ramanathan has been working on climate change for decades, and he famously pitched Pope Francis in a Vatican parking lot on why tackling the issue would help the world's poor. Although he's not Catholic, he's a member of the Holy See's official delegation at the Paris summit.

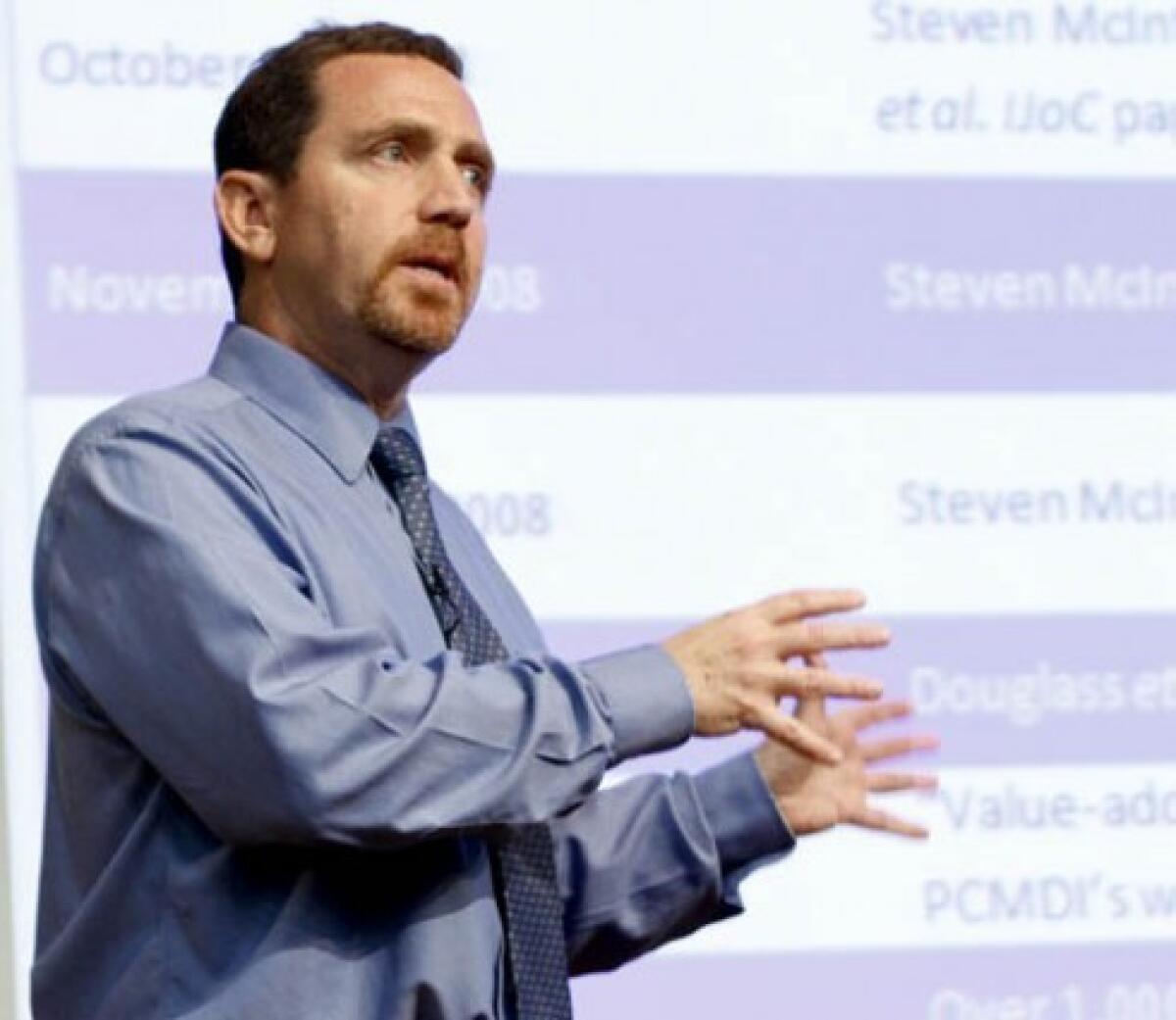

Ben Santer, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Ban Santer, an atmospheric scientist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, delivers a lecture.

Ban Santer, an atmospheric scientist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, delivers a lecture. (Jacqueline McBride / Newsline)

Two decades ago, Santer was in Madrid for a United Nations summit where he helped write a report concluding that the "balance of evidence" showed humans were contributing to climate change. He thought it would be a turning point for the world.

"I had very naively thought that the science alone was enough," he said. "People would do the right thing." Santer was wrong. He was accused of skewing the data, and the ensuing debate produced little progress. The experience changed his understanding of what it would take to battle global warming. "What I recognized that it was imperative not only to do the research, but to communicate," he said.

Santer's specialty is "fingerprinting," which means discerning which changes in the Earth's climate are caused by humans and which are natural. When Republican presidential candidate Sen. Ted Cruz told a late-night talk show host that global warming wasn't happening, the Brown administration asked Santer and another scientist to pen a response that was posted on a state website. "You have to push back against powerful politicians who argue it's a hoax, it's a conspiracy," Santer said.

Although he's not going to Paris for the United Nations summit, Santer is hopeful about its outcome. "The hard reality," he said, "always trumps ideology."

Anthony Barnosky, UC Berkeley, and Elizabeth Hadly, Stanford

Standing in front of prehistoric mastodon bones found in Southern California in 2001, California Gov. Jerry Brown speaks at a news conference at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in Los Angeles Monday, June 15, 2015. Brown says he wants California’s plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to be a model when global leaders meet to try and fashion a universal agreement to combat climate change. Brown also met with leading scientists to discuss the impacts of global warming and the need for action at all levels of government.(AP Photo/Matt Hartman)

Elizabeth Hadly and Anthony Barnosky watch Gov. Jerry Brown speak at the museum in June. (Matt Hartman/Associated Press)

Married scientists Barnoksy and Hadly live in a "house divided" over their allegiances to rival schools — he works at Berkeley, she's at Stanford. But in this field, they see eye-to-eye. Three years ago they collaborated on a study about climate change that painted a bleak picture, prompting Brown to pick up the phone. The governor said he was shocked by the severity of the scientists' finding, Hadly recalled. "If this is such a big deal, why aren't scientists shouting from the rooftops?" he said. Hadly said the governor had a request. "I don't understand this paper. Translate it," Brown said. "I want something I can throw on the desk of a business leader."

The result was a "consensus statement" on climate change signed by 520 scientists from 44 countries. Hadly said Brown had no influence over how they portrayed the science, but he weighed in on its presentation. The governor wanted a short summary with a simple font and only a few colors — something accessible for the average reader. "Earth is rapidly approaching a tipping point," said the first line of the report. Some scientists balked at the language, but Hadly defended it. "Without that language, it becomes way too diffuse," she said."It has a lot of validity and a lot of power."

They are in Paris for the summit.

The report has been translated into multiple languages, and Brown has distributed it eagerly, presenting copies to President Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping. The governor has also latched on to the "tipping point" phrase, mentioning it at a Vatican conference this year and peppering scientists with questions about the concept. "You could call it apocalyptic," Barnosky said. "But it's reality. That's where we're headed."

William Collins, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

William Collins, right, sitting in a meeting with Gov. Jerry Brown and Christiana Figueres, a top United Nations official on climate change.

William Collins, right, sitting in a meeting with Gov. Jerry Brown and Christiana Figueres from the United Nations. (Samer Momani / Caltrans)

Collins works on modeling climate systems, and he helped the United Nations write a major international report in 2007 that led to a Nobel Prize. Collins also has a side gig as a science advisor to the Climate Music Project, which uses climate data as the foundation for composing music. For example, the pitch could change along with the atmosphere's carbon dioxide content. "It's not intended to be easy-listening music," said Stephan Crawford, the group's founder.

While meeting with the governor, Collins recalled, Brown pushed for ways to address the issue -- "Tell me what the biggest levers are to push to make this happen," he said. Collins said the issue can provide new opportunities for the state as countries get ready to invest in green policies. "We're talking about reforming the world's energy system in the next few decades. Who's going to make that technology? This is a once-in-a-century opportunity for California."

Dan Cayan, Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego

Dan Cayan (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD)

For years, Cayan has been working with the state to produce reports on the impact of global warming. He specializes in examining how the changing climate will affect California and Nevada, particularly the dangers to mountain snowfall that's a crucial source of water. Since Brown took office, Cayan has been regularly surprised by the level of interest from the governor and his administration.

While former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger also made fighting climate change a priority, Cayan said Brown seemed more willing to dig into the science behind the issue. "It would be pretty commonplace for politicians to leave this to people on his staff," he said. "I don't think he's that kind of bird." On a recent night, one of the governor's advisors sent him and another scientist a question about how much warmer the planet is becoming, setting off a wide-ranging conversation. "You can always quibble with certain interpretations," Cayan said. "But I think they're sort of going the extra mile."

Follow@chrismegerian on Twitter

For more, go to latimes.com/politics.

ALSO:

California isn't a country, so why are so many in the state headed to climate talks in Paris?

Brown readies to take spot on global climate stage

Gov. Jerry Brown speaks at the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles in June.

Gov. Jerry Brown speaks to reporters in June while flanked by scientists at the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles. (Samer Momani / Caltrans)

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.