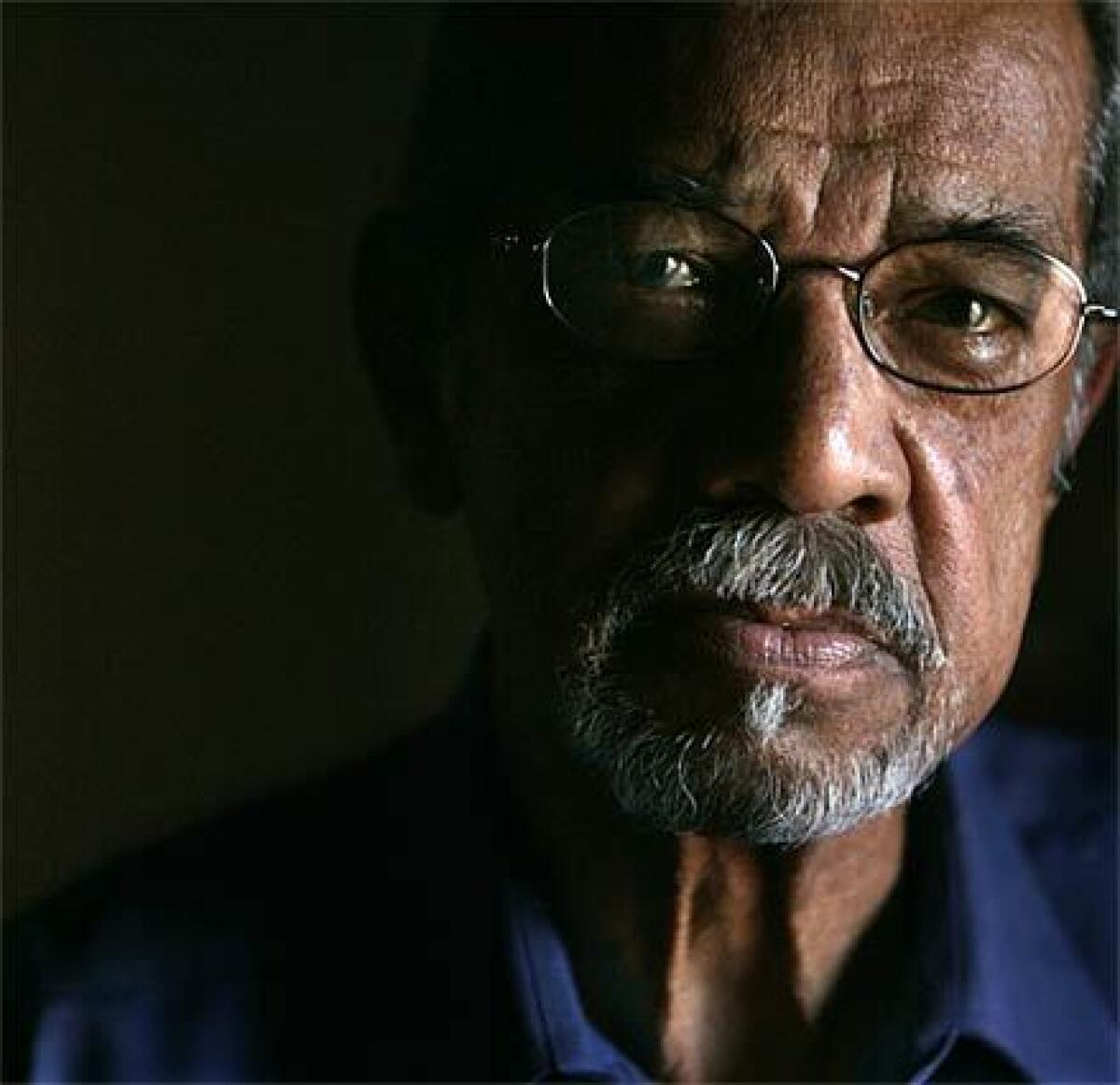

Realist with passion

This is the fourth in an occasional series of conversations with Southern California activists and intellectuals.

--

The evolving place of African Americans in Los Angeles culture and politics is a topic much discussed in the corridors of city influence, but rarely is it broached publicly or candidly. Many Los Angeles blacks fear that their political influence is waning, giving way to the rising Latino population in the southern and eastern reaches of the city and region. For their part, many Latinos view their black representatives warily, as artifacts of an earlier period in Southern California history.

Important though they are, those topics are tough to discuss because they are fraught with the potential for racial generalization.

Larry Aubry is an exception to that reticence. Deep in experience, both thoughtful and outspoken, he is a wise and energetic activist who has lived the travails and triumphs of African Americans and yet is able to see those experiences objectively.

Aubry came to Los Angeles, as so many blacks did, as part of the migration from the South to take work in Southern California’s wartime defense industries. That was during the 1940s, when Central Avenue was lifting off as a center of jazz but when whole parts of the city were explicitly reserved for whites. He went to Fremont High School, where, in 1947, blacks were hung in effigy. Posted signs proclaimed “No niggers,” and, later, blacks were barred from residing in -- even entering -- Inglewood. Aubry today lives in Inglewood, which now is heavily Latino.

He was a social service worker -- probation, mostly -- through two riots, the explosive Watts conflagration of 1965 and the wider, more depressing social breakdown in 1992, when rioters set stores afire and looted their way across parts of the city in protest over the acquittal of four Los Angeles police officers in the beating of Rodney G. King.

All of that was discouraging to witness, but it did not break Aubry’s spirit. He passed his 70th birthday a few years back and has seen more than enough to be circumspect, but he remains optimistic and resistant to cynicism. He is a respected columnist who has held a spot at the Los Angeles Sentinel for more than 20 years; he’s a father of five, proud to have raised them in an environment better than that of his youth but unsentimental about the obstacles they too face. The result: Aubry is a rarity in a city in which discussions of ethnic politics are too-often guarded or hedged. He is a passionate realist.

The focus of both his clear vision and his passion is, to a large degree, the changing nature of Southern California’s African American culture. His analysis is unflinching. Aubry likes Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, who is popular across much of the city, but acknowledges that the mayor is regarded warily by some blacks, particularly older ones. His attempt to take over the L.A. Unified School District, for instance, was cheered by most Latinos but viewed suspiciously by many African Americans, who worried that a Latino-run district would have little use for their children.

Aubry’s take on the complex question of where blacks are today begins in his youth. It forms around Central Avenue, once a hub of African American culture, a place he remembers for its jaunty ebullience and strong sense of community. The avenue today is in wretched shape, with long stretches of dilapidated buildings. Its demise strikes many as symbolic of the culture that gave it vivacity just a few decades ago.

“There’s no comparison,” Aubry says. “You’ve got structural deterioration. You’ve got demographic shifts. It’s a Latino area now. . . . It’s almost like apples and oranges, it’s so different. Back then, we had an affinity for each other, a whole lot of support. And you had a sense of caring and sharing that I just don’t see anymore.”

Central Avenue’s heyday came in an era of overt segregation. As those days gave way to subtler forms of discrimination, Aubry recalls, more nuanced divisions set in -- and blacks who once built communities splintered into class sects.

The crowning epoch of black influence in Los Angeles began in 1973, when Tom Bradley, a former LAPD officer and member of the City Council, became the city’s first African American mayor, sworn in on a sunny July afternoon by Earl Warren, the retired chief justice who had written the Brown vs. Board of Education decision 19 years earlier. Bradley went on to hold the office through five terms, making him L.A.’s most enduring mayor. But Bradley concentrated his reformist energies on building a downtown and integrating city jobs. South-Central and its poorer residents slipped further and further away from the mainstream, a bitter irony for those poor blacks who had hoped for so much from Bradley.

“South-Central went down on Bradley’s watch,” Aubry says. “They wanted like crazy to feel good about Bradley, but they saw very little coming from Bradley. Very little. There was the downtown thing . . . but South-Central got very little from him.”

Bradley’s mayoralty, while heroic in some respects, came to a crashing conclusion. The 1992 riots brought down Police Chief Daryl F. Gates, Bradley’s longtime nemesis, but they also finished off Bradley. He left office a year later, replaced by Richard Riordan, who won on the slogan, “Tough enough to turn L.A. around.”

Reflecting on the place of African Americans in the post-Bradley era, Aubry shares the widespread worry among blacks that Bradley did not take them far enough and that now, with Latino political power rising along with its swelling population -- legal and illegal -- African Americans may lose opportunities to exercise substantial leadership. Aubry declines to blame Latinos for this development, instead chiefly faulting African Americans, wondering whether they have lost the bond that once tied the community together in the face of more naked oppression.

“There’s a greater chasm between the black middle class and poor blacks than ever in history,” Aubry says, leaning forward on a couch in an upstairs nook of his Inglewood home. “How many middle-class blacks go east of Broadway these days? Not many. Not many.”

Will that change? Aubry argues that it can, but only if Los Angeles’ blacks bind together -- not to repel the advance of Latinos or to contest the racism of whites but to insist on their own political standing, to focus their attention on real obstacles, to hold their own leaders accountable for improvements and to demand their place in a multiethnic political spectrum. That expresses itself across an array of issues, he says.

Take immigration: “Most blacks look on immigration negatively: ‘They take our jobs, they do this, do that,’ ” he says. “Some of that is true, but it’s really not the immigrants’ fault. It’s the employers. They hire who they want to hire.” From the other side, he adds, Latinos too often sneer at blacks, accusing them of laziness and indolence.

With that, Aubry pauses to consider. As he does, his irritation builds visibly. When he speaks again, it is with new vigor.

“It’s a mess. I’m not so sure that my people have the will to assume the risks that are necessary to stand up, to call a spade a spade, to tell the elected officials who aren’t doing a damn thing to get off their butts and do something. Hold them accountable for doing that. . . . The black churches are sitting there, powerful as ever. When’s the last time you heard Chip Murray [former pastor at First AME Church] or somebody like that talk about Kevin Murray in the Assembly or Herb Wesson in the council or [former] Chief Parks?

“It’s a culture of silence. It’s a culture of accommodation. And therein lies a real problem for my people.”

That has been especially evident in recent days, he adds, as Martin Luther King Jr.-Harbor Hospital, born in the aftermath of the 1965 riots, has failed its final review by the federal government and is closing down. The hospital, originally known as Martin Luther King Jr.-Drew Medical Center, was an icon of African American Los Angeles, its staff and history zealously guarded by Supervisor Yvonne B. Burke. But Aubry criticizes Burke for letting the hospital founder and for its long demise. “King-Drew,” he says, “was a rhetorical priority, not a real, practical priority.”

For Aubry, real emancipation for blacks will come when those leaders perform better and when their constituents refuse to accept anything less.

“My fear is that my people are not sufficiently dissatisfied to behave differently,” he says. “If you don’t have your act together, you can’t collaborate effectively with anyone. And that’s what we need to do. We need to have an agenda, not a monolithic agenda, but a black agenda.”

And if Aubry were to write that agenda?

“No. 1, I’d like to see us free of fear,” he begins, speaking slowly now. “No. 2, I’d like to see an education system whose true goal, whose real goal, is excellence in education, not closing the achievement gap, which is bull. And frankly, right near the top would be my folks working in a sustained way with each other to improve conditions.”

That’s not here yet, he admits. But he’s been at this a long time, through progress and setback, through recession and riot, through leadership of all colors and politics.

“We have a long way to go,” he says, “but I’m looking forward to getting there.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.