Brown pushes cities, states to set tough environmental targets

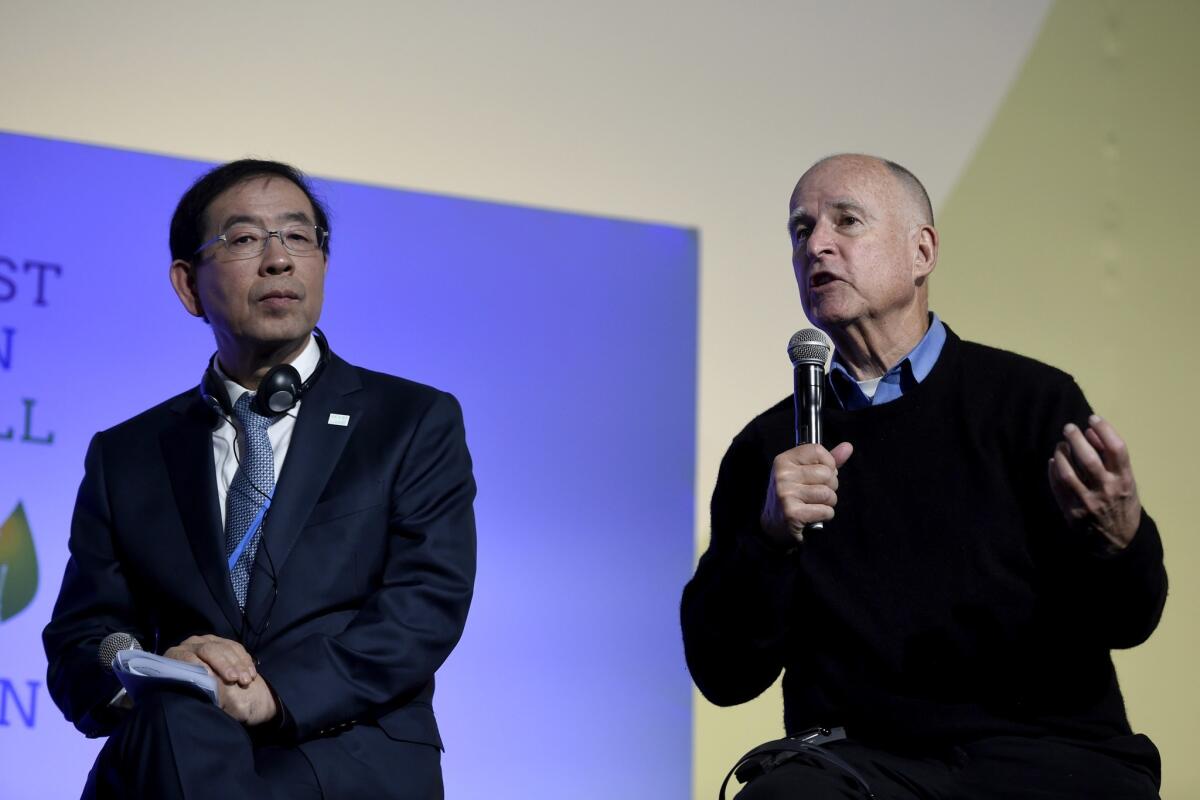

Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon listens to Gov. Jerry Brown during a working session for “Action Day” at the U.N. conference on climate change Saturday in France.

Reporting from Paris — More than a year and a half ago, Franz Untersteller, the environment secretary for the German state of Baden-Württemberg, stepped into a meeting with Gov. Jerry Brown in Sacramento.

Untersteller was visiting California to learn about energy policy, but the conversation shifted to how the two states — each regarded in its respective country for prosperity and environmentalism — could push broader, global action on climate change.

“Let’s think about what we can do together,” Brown said, according to Ulrich Maurer, a German official who was in the meeting.

The brief conversation was the genesis of an ambitious international effort celebrated here at the U.S. ambassador’s residence on Sunday. Brown and his allies have been rounding up states, provinces and cities willing to set environmental targets tighter than those that are likely to be adopted at the United Nations summit on climate change.

Fifteen more were added Sunday, and the total could exceed 100 by the end of the week — equivalent to roughly a quarter of the world’s economy.

“Thank you for being part of the crusade,” Brown said. “We’re not stopping here.”

The signing ceremony, which included leaders from Oakland, Seattle and Austin, Texas, was held in a baroque ballroom after a champagne reception with some of the governor’s closest advisors.

Jane Hartley, the U.S. ambassador to France, congratulated Brown and his allies for having “chosen to act before it’s too late,” and called the effort “a remarkable, remarkable achievement.”

The international accord is known as the Under 2 Memorandum of Understanding, or MOU, named for its goal of keeping global temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius.

None of the leaders signing the deal has a seat at the negotiating table during the United Nations conference, which is reserved for nations themselves. But by showing that smaller governments are ready to commit to tougher action, Brown has hoped to embolden the people responsible for hammering out a global climate accord.

“We’re going to be a force to reckon with, to make sure that our nation states do what they have to do,” Brown said.

The memorandum is not legally binding, and not everyone who joins necessarly sets new targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions — places like California already had stringent-enough goals to qualify.

It’s hard to say what impact the agreement will have. The next phase of negotiations at the U.N. summit is scheduled to begin Monday, and thorny issues involving financing clean energy projects and reporting emissions reductions still need to be worked out. It’s considered unlikely that a Paris deal would be strong enough to keep temperatures from rising less than 2 degrees Celsius.

“Just like any PR campaign, it’s not easy to measure the success,” said Maurer, who leads international efforts for the Baden-Württemberg environment ministry. “But we hope we can contribute to good results in Paris.”

Mark Kenber, CEO of the Climate Group, a London-based organization that has worked with California, said agreements among local governments could help fill potential gaps in a final Paris agreement.

“More and more we’ll be able to add up the impact of these individual initiatives,” he said, “bending the curve further” on climate change.

The agreement was also praised by U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, who last week said “it could be a game changer.”

Working on a global agreement was a natural fit for Brown, who has sought a larger megaphone on climate issues, and Baden-Württemberg, the only German state led by the environment-minded Green Party.

The job of drafting the paperwork fell largely to Ken Alex, a lawyer who worked with Brown on environmental issues in the state attorney general’s office. Now he’s one of the governor’s key climate advisors and directs the Office of Planning and Research.

After California and Baden-Württemberg agreed on a draft, Alex flew to a United Nations conference in Peru to rally more support. He said the response was positive, but he wasn’t sure how far that would go.

“I wasn’t sure the reaction was going to lead to signatures,” Alex said. “It’s always easy to say that’s a great idea.”

California officials began signing up places where the state already had working relationships, including Oregon; Washington; British Columbia; Ontario, Canada; and two Mexican states. Baden-Württemberg locked down Catalonia in Spain, Lyon in Italy and Rhône-Alpes in France.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Dec. 7, 10:23 a.m.: This article states that Lyon in Italy is one of the signatories to the environmental accord. The region of Lombardy joined the agreement.

------------

By signing the accord, states and provinces are committing to reduce emissions to at least 80% below 1990 levels, or less than 2 metric tons per capita, by 2050.

“You have to sell it, and convince the other regions that it can be a positive signal and a positive sign for Paris negotiations,” Maurer said.

The agreement was first announced in Sacramento in May, and Maurer said the goal was to have 50 signatories by Paris, a target they surpassed. It now includes some of Europe’s biggest economies as well as tropical forest states in the southern hemisphere.

In an interview before the trip, Brown said he would push to make sure other places follow through on their commitments after the Paris conference.

“It’s one thing to get someone to sign an MOU and have a picture taken. It’s quite another to actually do things,” he said.

Dealing with climate change, Brown said, is “not a one-time event. It’s day after day, fashioning and implementing actions.”

Twitter: @chrismegerian

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.