In a California farm town, the border is just a line that must be crossed every day

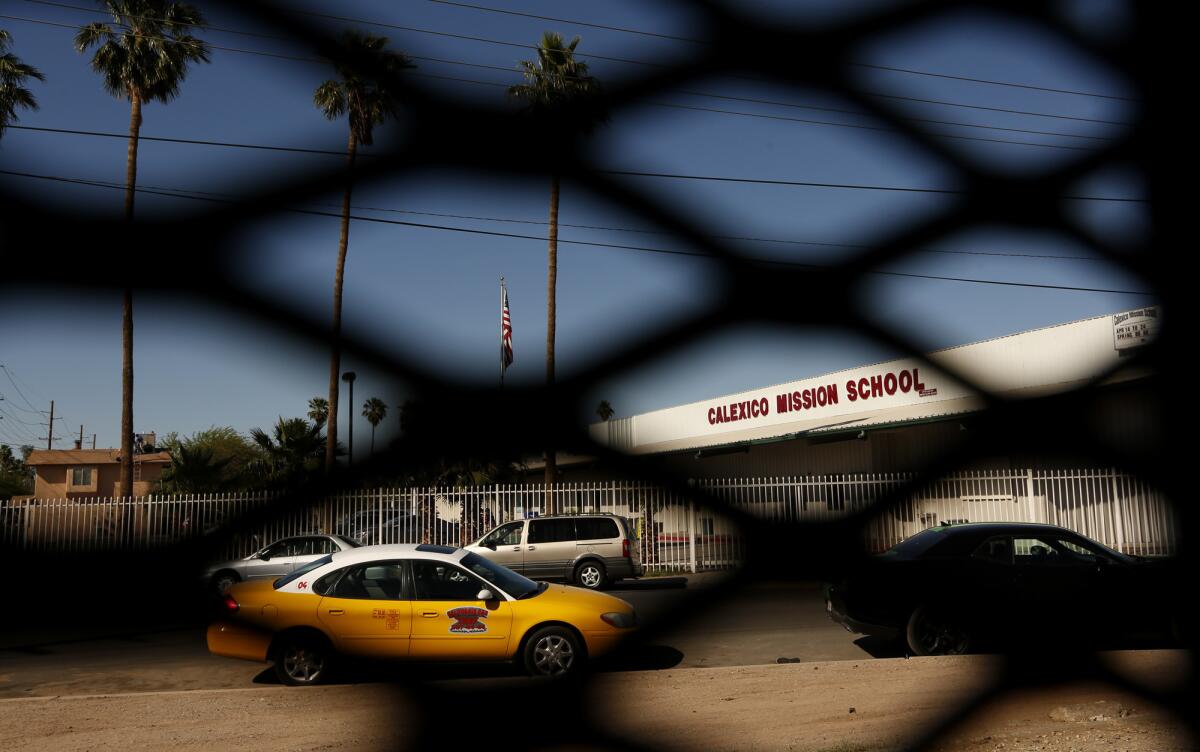

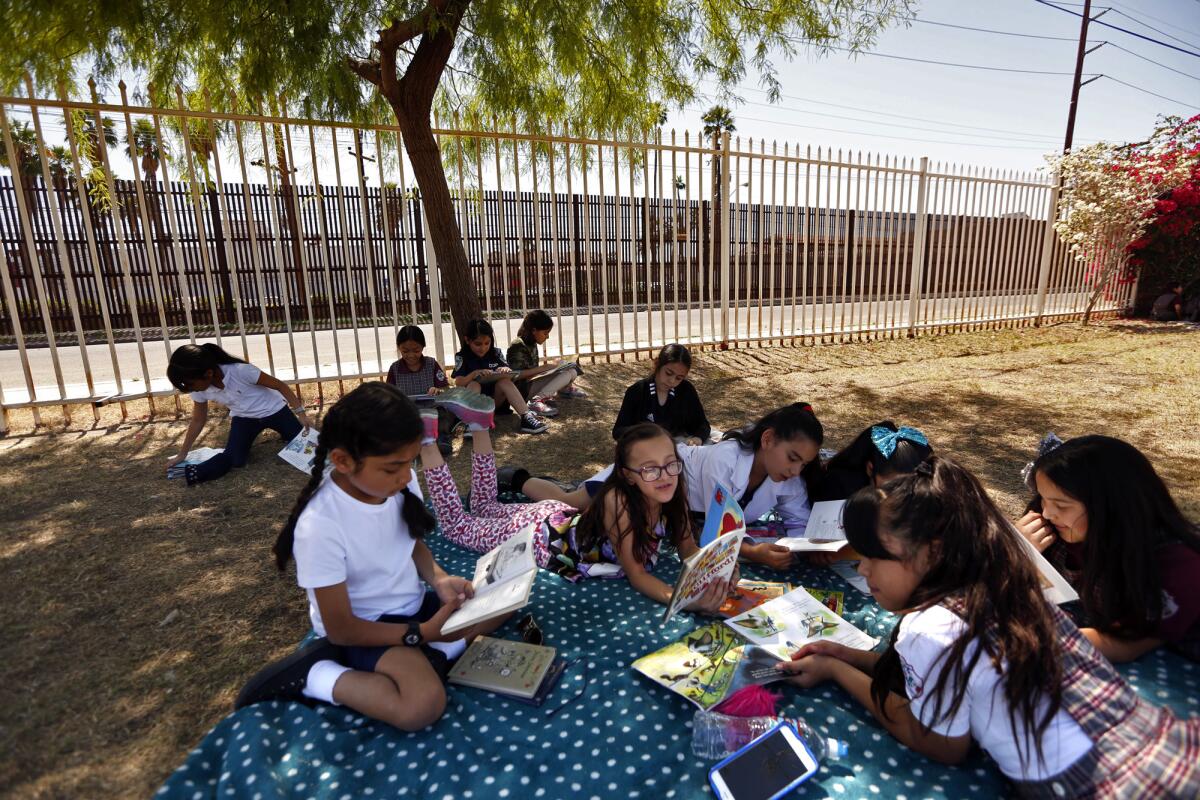

Reporting from CALEXICO, CALIF. — The schoolyard at Calexico Mission School is quiet, save for a stray giggle here and there. Third-graders huddle for reading time: the girls lying beneath a shade tree, the boys under a blazing pink bougainvillea.

Just beyond the school’s white picket fence looms the rusted 16-foot-tall steel fence that separates this farm town from the sprawling city of Mexicali, Mexico. The school sits about 50 feet from the fence — closer than a major league pitcher from home plate.

Through the steel mesh of the fence, children can see the ever-present line of cars on Avenida Cristóbal Colón waiting to cross the port of entry into the United States and hear the chatter from their Spanish-language radio stations.

When a Border Patrol agent pedals by on a bicycle, none of the students — virtually all of them Mexican children who cross the border every day — glance up.

In the era of Donald Trump and his talk of building an impenetrable — and “beautiful” — wall to beat back illegal immigration, the border has become a hardening line in America’s cultural wars.

But to many of the people here, the fence that separates the two countries is neither fully a bulwark against invasion nor a foreboding stop sign to immigrants’ hopes. It is a mundane part of the environment that must be crossed every day to live, work and study.

The border that divides Calexico in California and Mexicali in Mexico has for generations been more of a marker than a barrier.

In some ways, Calexico — a dusty, mostly Latino desert city of 40,000 — is today a suburb of Mexicali, which has become an industrial powerhouse and now has a population of around 700,000.

People have family on both sides. Calexico recently built an outlet mall next to the border fence to draw Mexican shoppers. And Mexicali has long drawn Calexicans to its nightlife, Chinese restaurants and cheaper medical care.

It’s one of several sets of “twin cities” along the border — such as San Diego and Tijuana and El Paso and Juarez — where deep economic, social, political and family ties belie the idea that the border should be a fortress.

“I love living on the border,” said Ailani Mares, 11, a Calexico Mission student from Mexicali. “Right now, I can say, ‘Oh, my mom and dad, they’re in Mexico, and I’m in the United States!’ It’s the best school ever.”

More than 8 million private vehicles and 4.5 million pedestrians cross through the cities’ two ports of entry into California annually, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Federal officials plan to spend $370 million to expand the Calexico West Port of Entry, building new pedestrian and vehicle lanes to cut down on long wait times.

“The border is something that keeps us apart in a way, but not really,” said Yolanda Johnston, a high school history instructor who’s been teaching at Calexico Mission for 44 years. “We just have to go through the line.”

In March, the Imperial County Board of Supervisors sent a letter to members of Congress, saying taxpayer money would be better spent modernizing the aging port than building Trump’s wall.

The port “is really vital to this area,” said David Salazar, Customs and Border Protection’s director of the Calexico ports of entry. “The local communities work together to keep business alive.

“There are very few people doing something wrong. Most of the people crossing are good, honest people.”

Calexico — a so-called melt-zone where homes and shops are just a quick dash from the border — was a hotbed for illegal crossings in the late 1990s and early 2000s after a high-profile San Diego crackdown called Operation Gatekeeper shifted immigration flows east toward the Imperial Valley.

The steel fence was built in 1999, replacing a chain-link fence, and hundreds more Border Patrol agents were added in recent years. Illegal crossings in the Imperial Valley have since plummeted — from 238,126 people in fiscal year 2000 to 19,448 in the 2016 fiscal year that ended Sept. 30, said Jonathan Pacheco, a spokesman for the Border Patrol’s El Centro Sector.

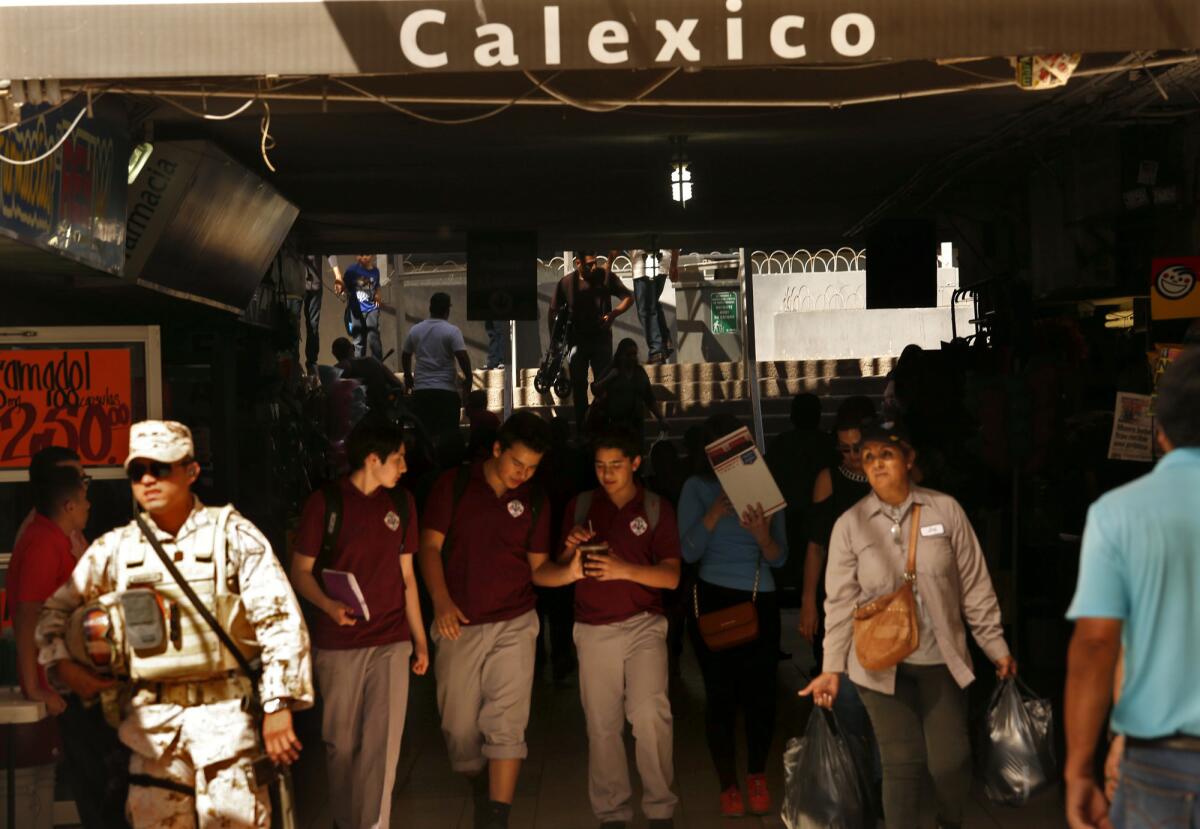

For most Calexico Mission pupils, who have student visas to make the crossing, the day starts in Mexicali. They wake up early, sit in traffic with their parents or in a carpool van and are dropped off at the port of entry.

They hustle along the scuffed pink-and-white tile in the port’s pedestrian tunnel, passing pharmacies, newspaper stands and tables laden with tamales and pan dulce before joining the long line next to a sign that warns of guard dogs on duty. From there, they walk a quarter mile to school, in desert heat that can hit 120 degrees in the summer.

Mariann Mendoza, an 11-year-old with shiny silver braces on her teeth, said she wakes at 5:15 a.m. and sometimes sneaks to bed wearing her school uniform so she can get a few more minutes of sleep. Her American classmate, Yasmin Corral, 11, from Calexico, giggled and said she felt kind of guilty because she can sleep in until 7:20.

The school was built 80 years ago by a group of Seventh-day Adventists who saw the border as a mission field for doing God’s work. Its logo includes both the U.S. and Mexican flags.

Of the Christian school’s roughly 300 students, about 85% are Mexican citizens. For many parents, the cost of the private school’s tuition — between $355 and $644 a month for different grade levels — is a worthy investment for an American education and the ability to attend an English-immersion school.

The school’s first-year principal, Oscar Olivarria, was once one of those students making the trek from Mexicali.

His wife, Tanya — who is of Russian descent and learned Spanish after growing up in East Los Angeles — teaches sixth grade at the school. Their children, Yakov and Vika, whose first and last names reflect their parents’ Russian and Mexican cultures, are students there.

About a third of the school’s students are on scholarship. Though many hail from upper- and middle-class families, their primary concerns center not on immigration but the economy.

“We have a population that is earning pesos and spending dollars, and when you factor in that exchange rate, it all of a sudden makes it very hard for those families to have their kids here,” Olivarria, 38, said. “Obviously, this is a priority for them and that’s why they make the sacrifice.”

The peso, which was sensitive to polls during the U.S. presidential campaign, plunged after Trump’s November victory. When the Calexico Mission school year started in late August, the local exchange rate was around 18 pesos per dollar. By January the peso, which has made a recovery recently, had depreciated to about 22.

Families questioned, month to month, whether they’d be able to keep their children in school, Olivarria said.

“As a school, we didn’t change our rates, but it’s as if we had,” he said.

Students can rattle off the exchange rate, which flashes on electronic signs when they cross back into Mexicali.

“We prayed for the dollar to go down, and it started going down,” said Ailani Mares, a sixth-grader. Her father is a doctor, and they do fine financially, she said, but it has been a scary few months for her class.

Just before the U.S. election, the sixth-grade class held a mock election of their own. Trump won.

Every day, the students said, they stand in border lines made longer by Mexicali youths who are illegally attending free, public Calexico schools. They pray aloud that the line will get shorter.

And that explained Trump’s victory as much as anything else.

Their experiences are distinct from those of untold children in America without legal status — who worry that they or their parents might be deported. But many of the students were also anxious about Trump’s win.

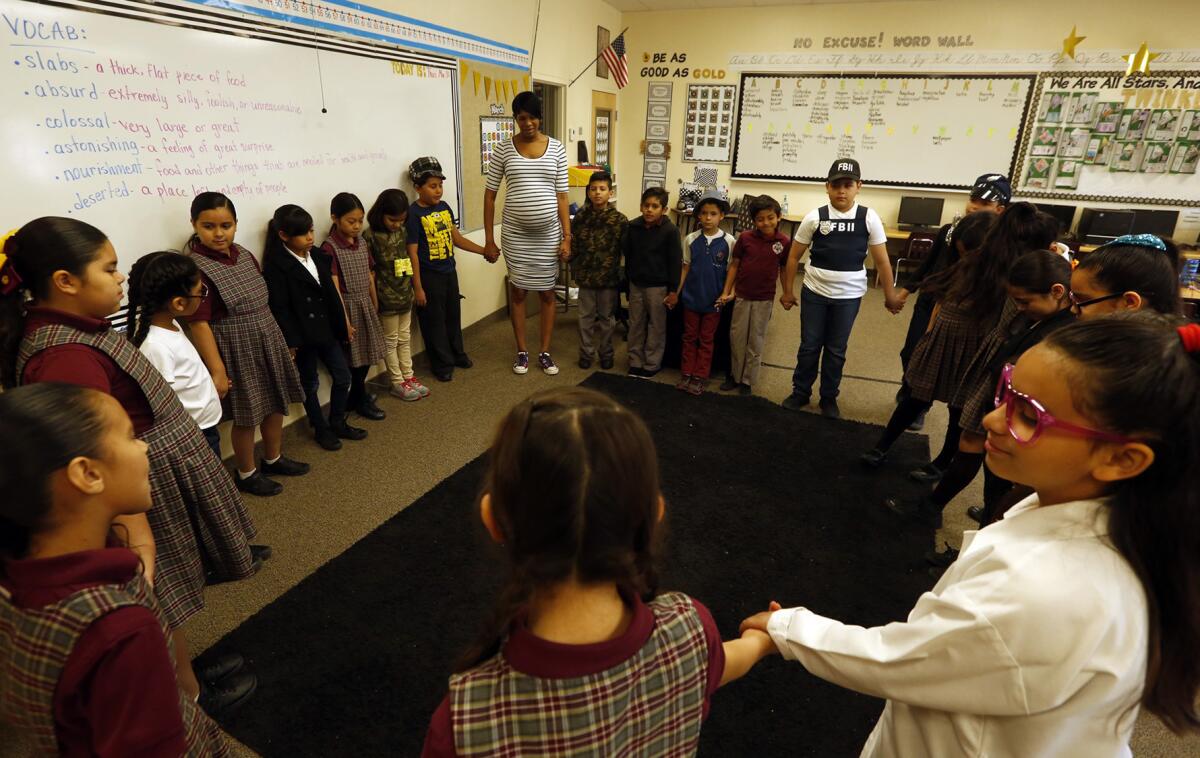

Tanya Olivarria’s students — and many parents — worried that if Trump won, they wouldn’t be able to cross the border anymore and would have to leave the school. Olivarria reminded them their visas were all legal and that they would not be taken away. If there was a wall, she told them, they would still be able to go back and forth.

“I told them God is in control, regardless if Trump or Hillary wins,” she said.

On a recent March morning, the students were far less concerned with border politics than that day’s election of the sixth-grade class officers, which was steeped in the steady influence of American pop culture.

Emilio Peña, from Mexicali, was running for class president and showed up in a suave black suit. He kept repeating his campaign slogan: “Vote for Peñas Care,” a riff on Obamacare.

A diminutive boy from Calexico, Miguel Felix, said his own slogan was “Short people matter.” Declared the new vice president, he celebrated by putting gold star stickers all over his face.

Yolanda Johnston was just out of college when she started at the school in 1973. Back then, people seemed to always be jumping the rickety chain-link border fence. They would duck into her classroom, knowing Border Patrol agents wouldn’t follow them inside. Students were unfazed. They would hand the person a book so he or she would blend in and move on with their studies without saying a word.

With so many Border Patrol agents on guard just feet from the school — and the big fence — that doesn’t happen anymore, she said. Occasionally, someone will still scale the fence with a ladder and sprint across the schoolyard, but, Johnston said, she feels safe.

At the end of a recent school day, a Calexico Mission student walking through the port to Mexicali bumped into a Mexican woman and apologized in English. The woman was surprised. The teenage girl laughed as she walked away with her friends, saying, “Se me salio!”

It just came out — referring to the English she accidentally blurted out.

Salvador Chacon, a wiry sophomore, waited for his mother to pick him up in the slow-moving parent traffic circle that forms every day in Mexicali by the port of entry, near Hotel del Norte.

This is his first year at Calexico Mission after attending school in Mexicali. His three older sisters are college-educated, and he knows his parents — who never graduated from high school — are sacrificing for him.

“My parents have no education,” he said. “That’s something that should limit them from doing things for us, but it doesn’t. I take that as motivation to strive in life.”

Once he started having to wait in line at the port each day, he gained a whole new respect for the farmers and laborers who do it too.

In the port of entry traffic circle the next day, Brenda Gallardo pulled up in a silver Suburban, and her three children — Jorge Noriega, 17, Ana Noriega, 11, and Patricia Noriega, 9 — piled inside.

Gallardo is a doctor with a bustling clinic that connects to the family’s two-story Mexicali home, a few blocks south of the border fence. She and her father — who grew up poor in rural Sinaloa — attended medical school at the same time, and he has a clinic next to hers.

She was horrified when the peso plummeted. Between her three children, it meant an extra 5,000 pesos a month in tuition. But she knew she would work as hard as she could to keep them in school.

“Education is the only way that we have to fight poverty, to fight corruption, to fight all the limitations that this country has,” Gallardo said. “The easiest thing for me to do would be to send them to the public school a few blocks from here. I wouldn’t be paying all this money. But I want better things for them than we in Mexico usually have.”

Twitter: @haileybranson

Photography by Genaro Molina

ALSO

A proposed statue with a Chinese face sparks resistance and debate in Monterey Park

This California sheriff bucks trend, calls for ‘anti-sanctuary’ policies on immigration

Feds say they didn’t deport ‘Dreamer,’ but acknowledge error on his DACA status

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.