From the Archives: How the 2003 gubernatorial recall changed California

Ten years after the Gray Davis recall, California was changed -- but not the way proponents hoped -- by the seismic election that propelled Arnold Schwarzenegger into the governor’s office.

SACRAMENTO — Ten years ago, California erupted in an anti-government, anti-establishment convulsion unlike any ever seen.

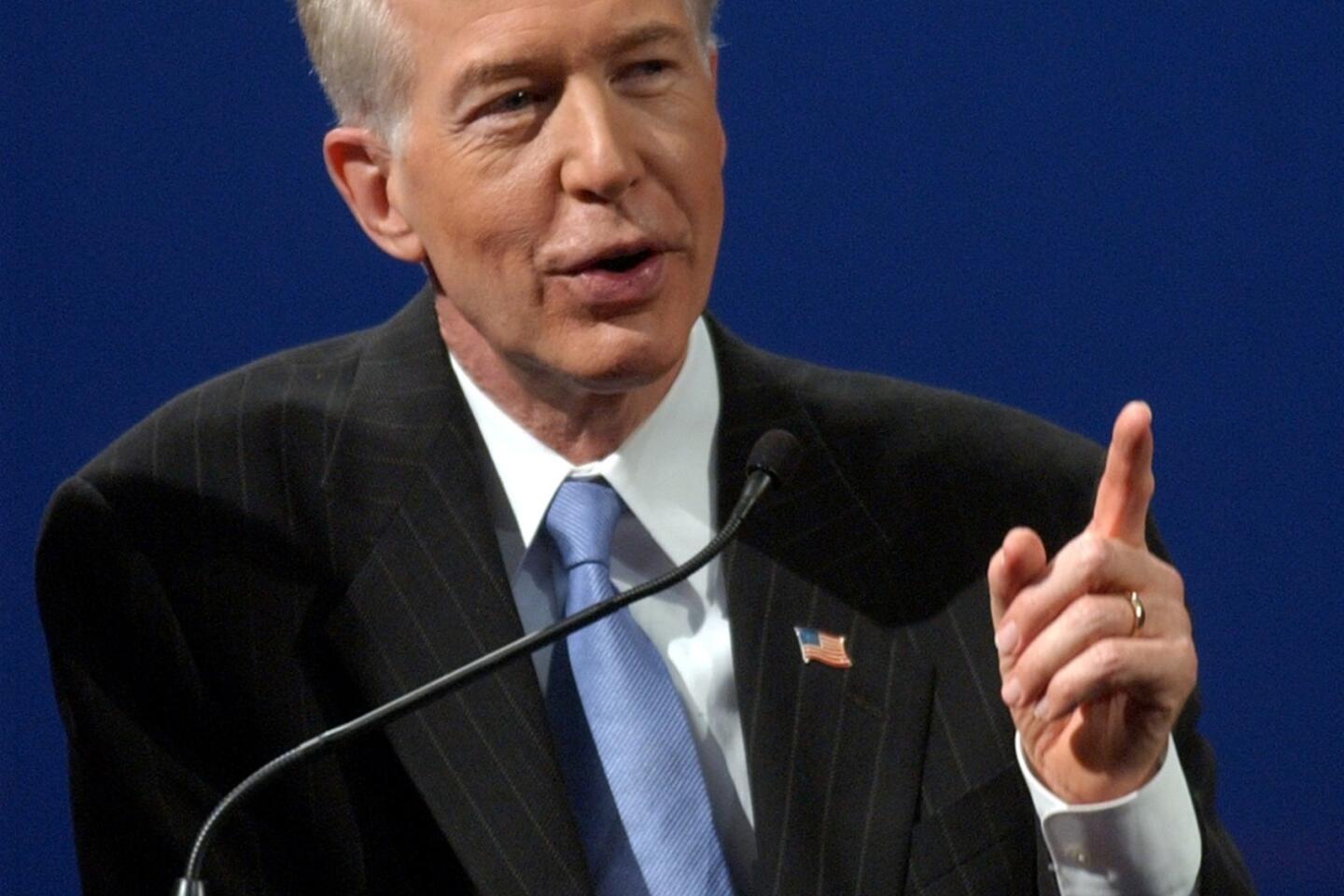

Disgruntled voters seized the chance for a rare do-over, recalling their staid and serious governor, Gray Davis, and replacing him less than a year after his reelection with one of the most famous and exuberant personalities on the planet. It was only the second time in U.S. history a sitting governor was booted from office.

The spectacle — a snap election featuring a color wheel of 135 candidates, including a former child actor, a porn star and a handful of professional politicians — shook California from its usual political slumber and captivated an audience that watched from around the world.

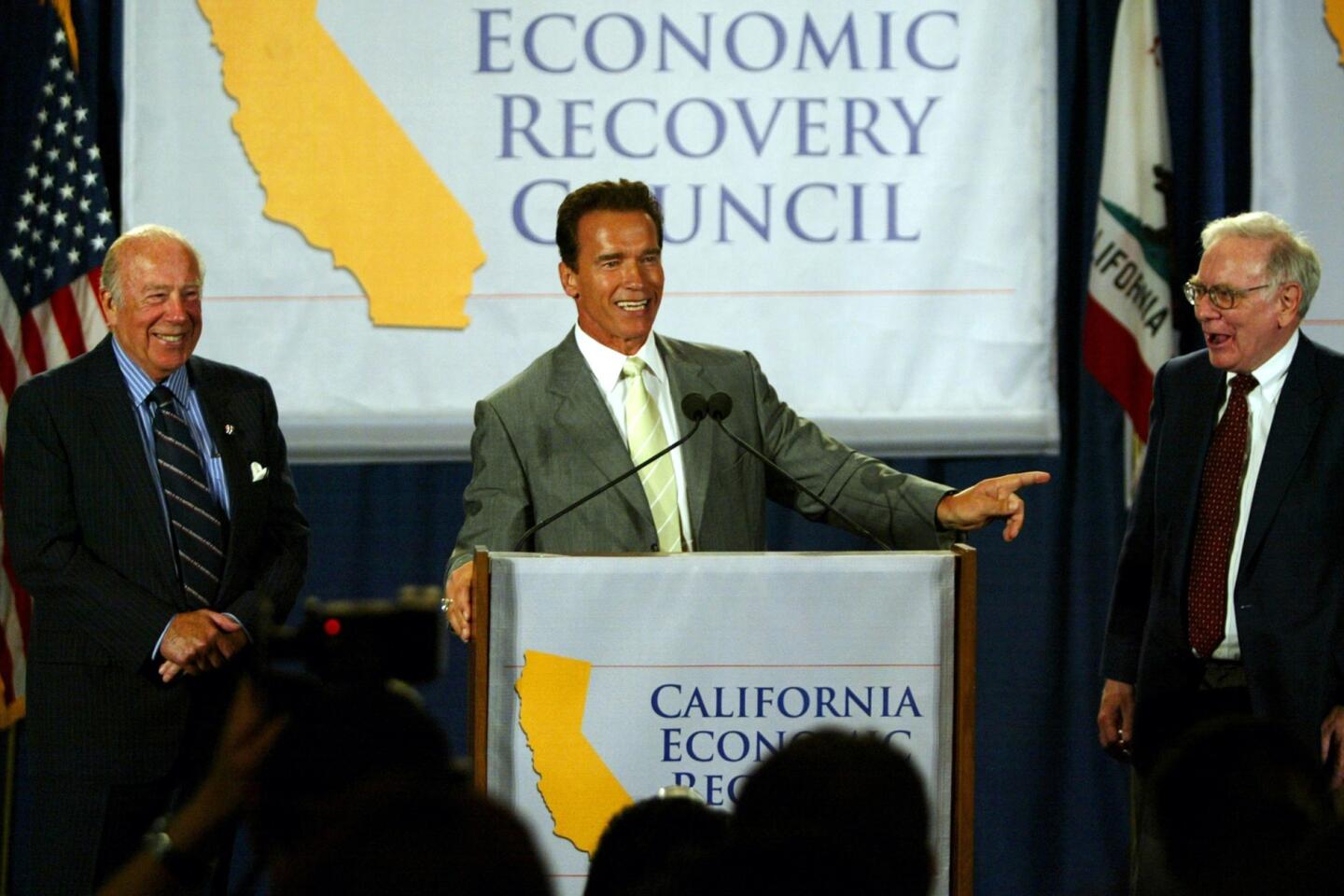

A decade on, the effects are still being felt, albeit subtly, and not the way proponents imagined, or the way actor-turned-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, the chief beneficiary, so grandly promised.

Fundamental changes in the way California elects its leaders — a top-two primary system aimed at pushing candidates to the ideological center and an impartial redrawing of the state’s political boundaries — will almost certainly change how Sacramento operates for years to come. Neither would likely have passed without Schwarzenegger sitting in the governor’s office.

The upheaval helped deliver the state its current governor, Jerry Brown, a decades-long officeholder and scion of California’s great political dynasty, whose worn-shoe familiarity appealed to voters in part because he was so unlike the upstart Schwarzenegger.

Less tangible, but also important, many say the historic election heightened awareness of state government and gave Californians a greater sense of empowerment, even if it failed to extinguish the flickering animosity toward Sacramento. For good or ill, the recall served notice on California’s political class, and still looms as a threat over all those holding elective office.

“There’s been a lot of momentum around fiscal and governance reform, particularly in the past five years,” said Mark Baldassare, head of the Public Policy Institute of California, a nonpartisan think tank. “The desire to make changes started with the recall but didn’t end with the recall.”

Still, in many ways the special election proved a failure, especially measured against supporters’ exceedingly high hopes.

The October 2003 ouster of Davis, a Democrat, was a primal response to the gridlock, partisan warfare, overweening special interests and mushrooming budget deficits that made the state capital a slough of dysfunction. “It was about changing the entire political climate of our state,” as Schwarzenegger, a Republican, said in his first inaugural address.

When he left office more than seven years later — after sinking to the same abysmal poll ratings as Davis — the special interests were just as firmly entrenched in Sacramento, the partisan rancor was unabated and the budget deficit had more than doubled.

Among the most bitterly disappointed were those who had the greatest hand in forcing Davis from office and paving the path for Schwarzenegger’s election, which was sealed in a separate vote on the same ballot.

“There was no substantive nuts-and-bolts change to California government, which was one of the main goals,” said Ted Costa, the anti-tax crusader who launched the main petition drive that qualified the recall, sparking the brief, intense and sometimes zany campaign. Costa has largely retired from politics, owing partly to his frustration over the outcome of the recall.

That view overlooks Schwarzenegger’s significant achievements, including an overhaul of the worker’s compensation system, savings in welfare and healthcare programs, and meaningful pension and retirement concessions wrung from public employee unions.

He signed landmark legislation to fight global warming. Working with Democrats, Schwarzenegger also ushered the state into its most ambitious rebuilding program since the era of Brown’s father, who oversaw the infrastructure development that still serves California half a century later.

Those accomplishments pale, however, when laid against the extravagant promises made during the recall. Schwarzenegger vowed to slash the size of government, stop deficit spending and end the pay-to-play culture of Sacramento, which he captured with stark simplicity in a TV spot: “Money goes in. Favors go out. The people lose.”

None of those changes occurred, as Democratic, Republican and nonpartisan observers point out.

“In the larger sense of dramatically changing the direction of the state, we didn’t accomplish what we’d hoped and expected,” said Rob Stutzman, a GOP strategist who served as a Schwarzenegger spokesman during the recall.

Even the former governor has said he could and should have done more to address the structural problems — a boom-and-bust tax system, a crazy-quilt budgeting process — that continue to plague the state.

“It was a mistake,” Schwarzenegger said in an interview before leaving office in January 2011. Instead of borrowing to paper over the deficit and add to the state’s mountain of debt, he said, “I should’ve gone the other direction to early on solve the budget problem and use the political muscle I had that first year in office.”

Still, even some let down by Schwarzenegger consider the recall a good and healthy thing.

“Once they’re elected, politicians become so isolated,” said Dave Gilliard, whose political group, Rescue California, helped orchestrate the signature-gathering with a $2-million contribution from Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Vista), who hoped to replace Davis but quit the race after Schwarzenegger got in. “Being mindful of their accountability to voters — that they can make changes — there’s nothing more American than that.”

It is highly unlikely anyone voted in October 2003 believing the result would be a top-two primary system aimed at weeding out extremists from the two major parties, or thinking Davis’ exit would mean an end to the self-interested drawing of political lines by sitting lawmakers. But those important structural reforms were enacted in good measure because Schwarzenegger, alone in the Capitol, was beholden to neither the Democratic nor Republican establishments (both of which opposed the ballot measures).

“He blew up the most important boxes of all,” suggested Susan Kennedy, a former Davis aide who served as chief of staff in Schwarzenegger’s second term, borrowing a line he used in the swaggering days after the recall. “That is changing the election system.”

Those changes, which have yet to be fully felt, may be the most important legacy of Schwarzenegger and the recall: If they work as proponents hope, Sacramento and Washington will eventually be populated with a breed of lawmaker less yoked to partisan interests and more amenable to compromise. That could be a big step toward solving the problems that sent angry Californians storming to the polls a decade ago.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.