Budget-modern: An architect’s low-cost Laurel Canyon house

By Jeffrey Head

The rear of John Frishman’s house consists of walls of glass looking out onto his deck and city views beyond. The trellis system was Frishman’s alternative to large steel beams, which he feared would have encumbered the space and escalated costs. He collaborated with an engineer to develop the system of smaller supports that ultimately provided structural support at a lower price. The floor is slate, inside and out. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Architect Jon Frishman spent 10 years building his 1,500-square-foot house in Laurel Canyon, planning meticulously to save money and knocking out projects bit by bit. The result: A modern retreat on a relatively modest budget.

Rather than devote space to a two-car garage that he didn’t need, Frishman designed a one-car garage and an adjacent garden courtyard that, thanks to a sliding front door that the architect installed and a retractable fabric awning that he has planned, can double as a carport. Frishman built the sliding door using aluminum tubes for the frame. He chose glass that is patterned for privacy, tempered for strength and only 1/16-inch thick to keep weight and cost down. “I would guess you could get a garage door fabricator to make one up for $2,000,” he said. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

The entrance to the house, which is the middle of three levels. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Frishman in his living room on the main level of the house, which takes full advantage of the view. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Mitered glass provides unobstructed views, even around corners of the house. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

In the kitchen, the backsplash consists of drywall painted yellow and topped with a 1/16-inch piece of clear tempered glass, which is strong, easy to clean and heat resistant. It’s also less expensive than tile often chosen for modern homes. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

In the kitchen, faucet knobs were placed near the front of the counter to eliminate the need to reach over the sink. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Another view of the kitchen, looking toward the living room. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A 1950s Russel Wright mug, a keepsake that once belonged to Frishman’s mother. In the background is a hood ornament statuette that his mother received when she bought her 1964 Lincoln Continental. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Glass stairs help to transmit light from the skylight above. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

The skylight is a simple piece of laminated, tempered glass. “It’s durable and fire resistant,” Frishman said. “You can walk on it, and it’s easy to clean with a squeegee and less expensive than a prefabricated plastic skylight.” (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

In the bathroom, where designer fixtures can easily hit four figures, Frishman bought industrial Chicago Faucet fixtures “in the $300 range.” The trick, the architect said, is to mix and match standard parts to create something different — “like taking a kit of parts and reconfiguring them.” (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

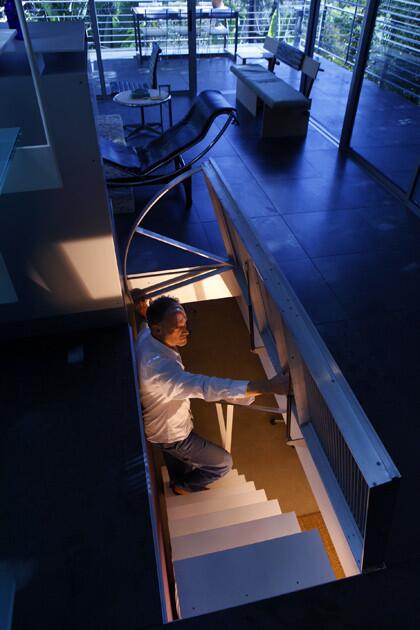

Stairs lead down to the lowest floor of the house, where Frishman has his office. A metal trap -- “a door in the floor,” Frishman said -- can swing shut, making the most of every inch and creating a stronger division between work and leisure space. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Frishman added interior details that recall the levers, knobs and switches of classic sports cars. Air grilles throughout the house are akin to the side panel vents you might see in a luxury car. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

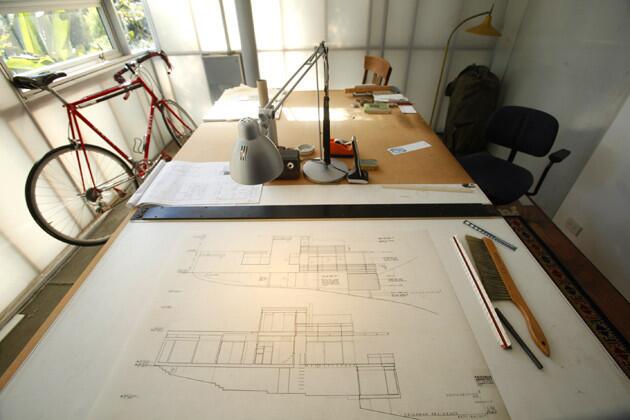

In the office, the walls have standard wood framing fitted with polycarbonate panels, inside and outside, which transmit light while still offering privacy and framing views. The polycarbonate provides less insulation than traditional walls, but radiant floor heating keeps the room comfortable in winter, and on the hottest days of summer Frishman has a shading device that covers the east-facing wall. “I have been looking for some type of bubble wrap to use as insulation,” he said, “but that is a work in progress.” (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

A matchbook from a defunct Manhattan restaurant rests against a vintage ashtray. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Back on the main floor, an industrial-looking light fixture hangs over the dining table. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

A post-storm sky, framed by the trellis structure. You can read Jeffrey Head’s full article on the Frishman house, posted to our L.A. at Home blog.

More profiles: Homes of the Times (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)