Most Read in This Section

-

Nov. 5, 2024

-

-

-

Nov. 5, 2024

By David A. Keeps

Architect John Bertram lives in a historic 1939 Richard Neutra house and is clearly influenced by the innovative modernist icon known for homes that connected indoor and outdoor spaces. “One thing that I love about Neutra’s buildings is that they are made of interlocking planes, almost like a house of cards,” says Bertram, who recently completed this Beverly Hills residence. Built on a flat lot, the house is animated by stacked roof lines with deep eaves and steel fascia trimming, dramatic structural walls that jut out into the landscape and multiple bands of cornered windows -- all part of Neutra’s vocabulary. “Even though it’s a relatively simple two-story structure, it has the feeling of a cube-shaped house that is flying out of control and unraveling into space,” Bertram says. (Christine House / For The Times)

The exterior of the house designed by Bertram and his Bertram Architects associate Eliot Mitchell features a stainless steel driveway gate and a steel pergola over the terrazzo pavers leading to the front door. The brushed stainless steel address numbers echo the Neutra look.

“Part of the wonder and beauty of Neutra’s compositions is a very subtle asymmetry that is, nonetheless, balanced,” says Barbara Lamprecht, the author of two books on the architect. “This house is absolutely and carefully calibrated with very specific views and openings to the outside that is obviously an hommage to Neutra.” (Christine House / For The Times)

The view from inside the visitor’s gate is almost fortress-like. Behind the wall, the solid smooth-coat stucco monolith to the right contains a skylit staircase in the center of the home. Beneath it, a massive walk-in closet has a band of clerestory windows that, Bertram says, “gives the appearance that the roof is floating off.” In front of the split-face Belair limestone wall from Haussmann Stone , a palo verde tree softens the hard geometric lines of the house. (Christine House / For The Times)

Inside the front door, an 18-foot-long split-face limestone wall floats in the center of the house. On the left side of it is the foyer, with a walnut display niche that is inset into the wall. The glass-walled living room lies beyond. To the right, the wall defines a walnut-paneled dining room and, to the rear of the house, a family room with a raised hearth fireplace built into the limestone. (Christine House / For The Times)

Reflected in the mirror of the first floor powder room is the staircase with treads fabricated by Hermosa Terrazzo and glass rails with a steel banister. “I like the idea of a big, machine-like stair case that looks like sculpture,” Bertram says. “But even though it is heavy, you can see through it because of the glass and the floating treads.” (Christine House / For The Times)

A reverse shot of the powder room illustrates the Neutra effect of massive, visually seamless surfaces and Bertram’s interpretation of the technique in upscale materials. By pushing the room outward, the limestone wall on the exterior house becomes an interior wall in the room and is played up with a sidelight window. The mirror connects the walnut countertop and a tall cabinet made with a single sheet of walnut veneer. Echoing the reflective mirror is a polished stainless steel sink by Intra and a Vola faucet designed in the late 1960s by Arne Jacobson. (Christine House / For The Times)

The family room has a custom floor-to-ceiling media center and is decorated with contemporary seating and a 1940s cork-topped coffee table by Paul Frankl. The corner window disappears into the view because the frame holding the glass in place is concealed inside the ceiling, posts and window sill. “If something has a frame, you can’t pretend that it’s not there,” Bertram says. “With this technique nothing stops your eye and reminds you that are looking at a window.” (Christine House / For The Times)

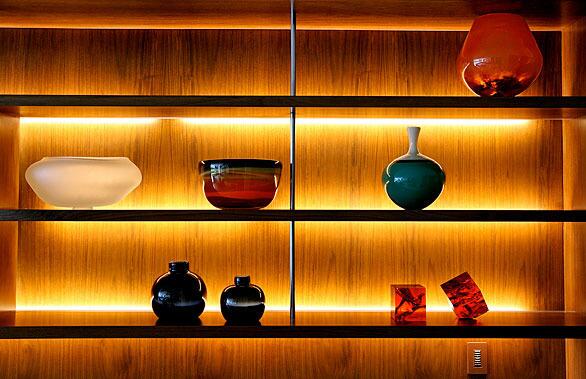

In the vast kitchen, Bertram’s sleek cabinetry design included open display shelves made from walnut with stainless steel support rods. They’re illuminated by concealed linear accent lighting from Tivoli . (Christine House / For The Times)

The kitchen island exceeded five feet, the standard size for stainless steel sheets, so Bertram designed the top as a windowpane with four pieces united by walnut trim. Across from it, a stainless steel counter at the same height extends outside the kitchen and into the patio. The windows can be folded and stacked, creating an oversized pass-through for entertaining. (Christine House / For The Times)

In the 8.5-foot-tall dining room, Bertram faced a similar dilemma with a picture window: “It was too large to be a single piece of glass,” he explains. “It’s very hard to get glass larger than 60 square feet, so we broke it into four irregular panels with walnut mullions.” The walnut-paneled wall, which has a pocket door for privacy, also required a non-standard 10-foot sheet of veneer. Uninterrupted walls and recessed doorjambs were a Neutra signature, Bertram says. “The door may not go all the way to the ceiling, but there would be a matching wood panel above it that would, which is a fantastic and handsome detail.”

Though the dining room is many more steps away from the kitchen than in most houses -- traditional or modern -- Bertram says the owners, who have a young son, don’t treat it as a formal space: “They say they use it all the time,” he says. “The view is amazing and you feel like you’re in a little private room in the mountains.” (Christine House / For The Times)

“The owners wanted nothing in the master bedroom,” Bertram says. The architect was happy to oblige, building a glass skybox with a 10-foot-4 ceiling, exposed structural supports and a simple cork floor. From the entry, what appears to be a wooden half wall turns out to be the back of a headboard with attached nightstands. Outside, the flat roof of the living room forms a 150-square-foot terrace. Flooded with light, the room can be darkened and cooled with the aid of motorized recessed Sivoia shades by Lutron . (Christine House / For The Times)

This east-view bedroom window is actually made from a Fleetwood Norwood sliding door and serves as a window in the room. The lights are Wohlert pendants from Louis Poulsen . (Christine House / For The Times)

“For their son’s room, the owners were looking for something whimsical that would still look cool as he got older,” Bertram says. The solution five matte white Borden ceiling lights in three sizes that look like a cluster of flying saucers, a perfect complement to the boy’s collection of action figures on Bertram’s built-ins. Below a floating shelf, the desk unit integrates a long work surface, book shelves and drawers with notched finger pulls that was inspired by a similar configuration in the Neutra home where he lives. (Christine House / For The Times)

On the terraces, Bertram wanted nothing to distract from the view. He installed a flush-mounted stainless steel trench drain and a railing made from frameless glass panels that are mounted in brackets concealed beneath the terrace floor. As a complement to the clean look of their private outdoor space, the owners added a Frog chair, a 1996 design by Piero Lissoni for the Italian firm Living Divani . (Christine House / For The Times)

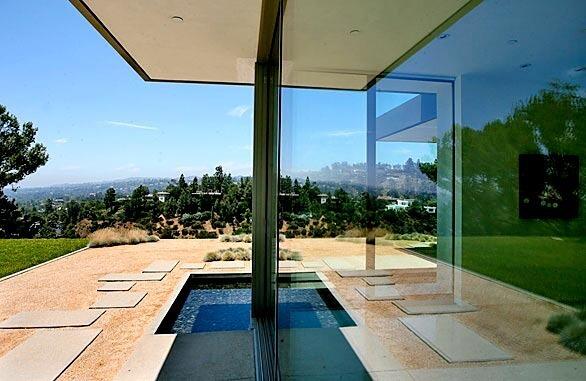

Off into the sunset: The western view includes a reflecting pool that wraps around the corner of the glass-walled living room. From the inside, the owners can open a slider and walk across the pond on elevated concrete pads.

“Neutra established a series of rules to design a house, and one that I relate to is that you attempt to break things down into volumes that can be broken down into planes that are most often rectangles,” Bertram says.

It is a rigorous concept of design that he takes seriously, but in this project Bertram has also found a way to deconstruct it in a fun way: On a bed of decomposed granite gravel, he had concrete poured into pavers, left, that echo the geometric shapes in the house. Laid out on the ground, it almost looks like he had constructed a scale model house-of-cards and then knocked it down.

Home galleries galore: www.latimes.com/homesofthetimes (Christine House / For The Times)

Nov. 5, 2024

Nov. 5, 2024