Crenshaw Boulevard comes to a crossroads

As Los Angeles’ boulevards reassert their place in the public realm, the transformation along Crenshaw offers glimpses of a new city identity taking shape

One of the best places to get a quick sense of how Crenshaw Boulevard has evolved in recent years is through the plate-glass windows of Earlez Grille, the popular quick-serve restaurant known for its chili dogs and tamales. Looking north toward the wide intersection of Crenshaw and Exposition boulevards, the view is dominated by trains pulling into the new Expo Line light-rail station and, beyond that, the sleek, curving facade of the West Angeles Cathedral.

This is the L.A. intersection in its emerging 21st century incarnation: full of cars, to be sure, but also kids in school uniforms on bikes and a steady stream of pedestrians heading to and from the Expo Line, which opened in April.

Earlez itself will be moving about a year from now to make way for yet another light-rail route, the $1.7-billion Crenshaw Line, which will run north-south along Crenshaw Boulevard.

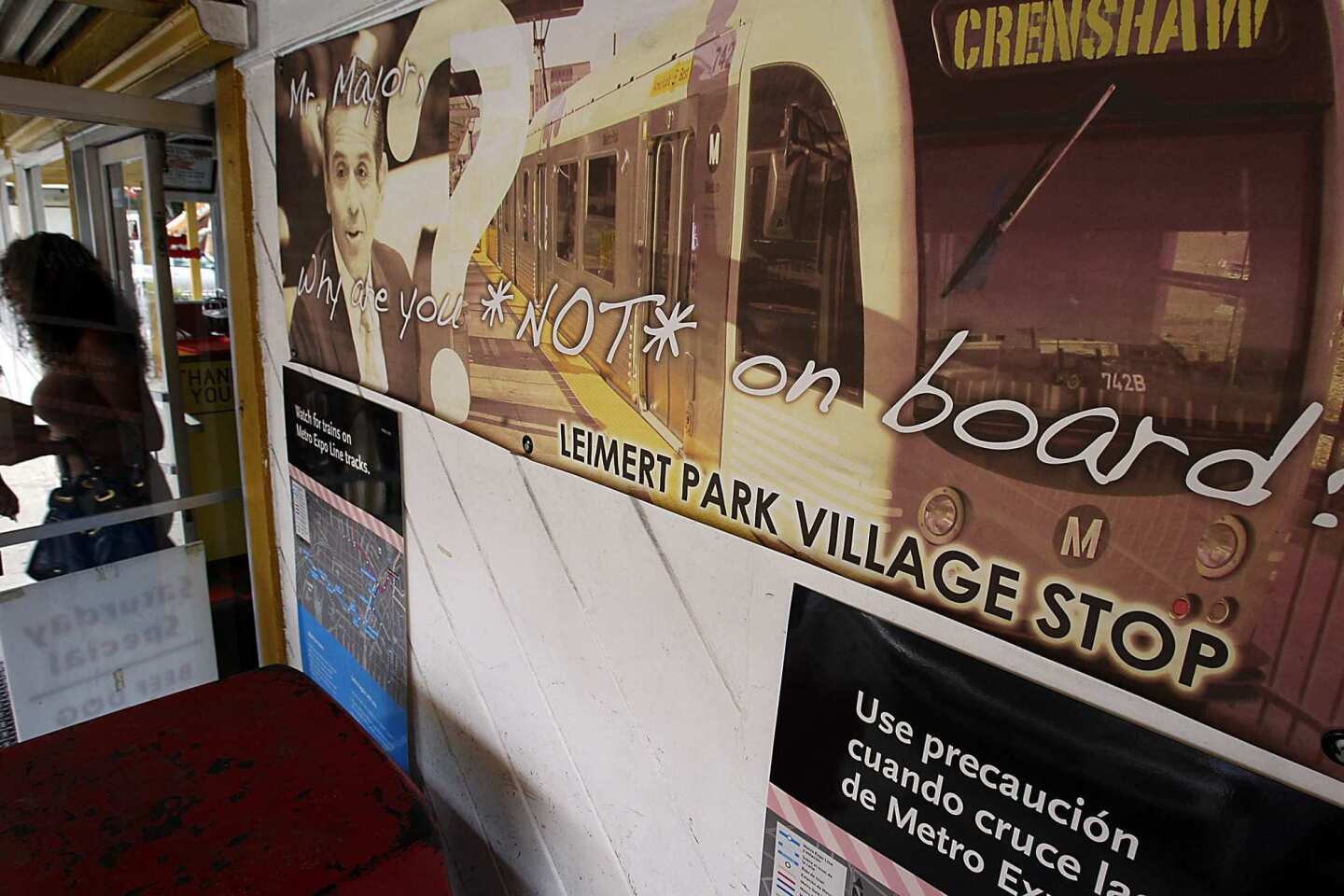

You'd think that might sour Cary and Duane Earle, the brothers who run the restaurant, on the idea of light-rail. But they have been outspoken in supporting it -- and in campaigning for an additional station on the Crenshaw Line a mile down the boulevard. A large banner on the restaurant features a picture of Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, a silver rail car and the words "Mr. Mayor, Why are you NOT on board?" Along the bottom it reads, "Leimert Park Village station."

Metro Expo Line rail cars roll past Earlez Grille at the intersection of Crenshaw and Exposition boulevards. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Even as the city of Beverly Hills goes to court to block a planned subway line, residents, shopkeepers and politicians in the Crenshaw district have lobbied hard for a Leimert Park station.

Just below the surface of that lobbying -- and in the tone of the banner, somehow defiant and wounded at the same time -- is palpable anxiety about the future of the Crenshaw district. It is anxiety about the fate of L.A.'s traditional center of black political and economic power in a city that is increasingly Latino. It is anxiety about being overlooked and underappreciated.

And it might just be the dominant characteristic of the Crenshaw district these days.

Crenshaw Boulevard, 23 miles long in all, begins and ends in wealth. It starts at Wilshire Boulevard, a few blocks from Hancock Park, and winds up in Rancho Palos Verdes at Del Cerro Park, a quiet green space with a panoramic view of the Pacific Ocean.

In between, the boulevard, named in 1904 for real estate developer George L. Crenshaw, takes on a remarkably diverse collection of personalities. Just south of Wilshire it cuts through a corner of Koreatown before running the length of the Crenshaw district and, further south, passing the huge ExxonMobil refinery in Torrance.

There are stretches where Crenshaw narrows and assumes a domestic feel, and others, particularly around Slauson Avenue, where it grows to more than eight lanes wide and impersonates a freeway. There are plenty of pockets where these extremes are uncomfortably mixed together, where single-family houses with tidy lawns line up across the boulevard from Winchell's Donut House and Launderland.

The sun sets on the Pacific Ocean in a view from Del Cerro Park, at the southern terminus of Crenshaw Boulevard in the Palos Verdes Peninsula.(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Historically, there has been one element capable of unifying this long and diverse thoroughfare: transportation.

In the early decades of the 20th century, streetcars carried passengers along the boulevard and private airfields lined the east side of Crenshaw just south of Jefferson Boulevard.

Once the neighborhood began to attract large numbers of African Americans after World War II, thanks to the loosening of racial covenants that kept blacks from buying houses in the area, aerospace companies on Crenshaw Boulevard in Hawthorne and elsewhere provided a steady supply of middle-class jobs.

During the 1960s and '70s, cruising and low-rider culture thrived along Crenshaw and became indelibly connected with the L.A. rap scene during the late 1980s and early '90s, when carfuls of young African Americans filled the boulevard every Sunday evening.

By that point the infatuation with cars and car culture had already made a mark on Crenshaw's architecture. In 1968, Tom Wolfe wrote an essay for the Los Angeles Times celebrating the "electrographic" architecture of Southern California's billboards and strip malls.

Wolfe singled out the Ford dealership at Crenshaw and 52nd Street, calling it one of the first pieces of architecture in the country "designed to express not a structural form but a graphic form.... The corner was designed solely to accommodate the shape of the F in Ford."

But the notion of the boulevard as a major transportation corridor -- a thriving center for planes, trains and automobiles -- has faded in recent years. Many of the aerospace companies and car dealerships have closed or moved, taking thousands of jobs with them.

"Inglewood and Hawthorne definitely aren't what they were," said Damian Pipkins, a 35-year-old African American who grew up in the Crenshaw district and now works at Eso Won, the bookstore just off Crenshaw Boulevard in Leimert Park. "Really, most of Crenshaw south of Vernon is pretty desolate. There's even a KFC that closed down. I mean, how do you close down a KFC at Slauson and Crenshaw?"

Leimert Park was designed between 1926 and 1928 by the Olmsted Bros. firm. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Pipkins' father worked as an engineer in the 1980s and '90s, when the southern end of Crenshaw still had a solid economic base. And though there have been stirrings of an aerospace revival in the last few years, it is a complicated one that reflects how often the efficient high-tech economy can leave middle-class workers sidelined.

Elon Musk, the serial entrepreneur who helped found PayPal and the electric-car company Tesla, five years ago moved the headquarters for his new company, Space Exploration Technologies, or SpaceX, to the corner of Crenshaw and Rocket Road, just south of Hawthorne Municipal Airport.

From the outside, the giant SpaceX warehouse looks much as it did when it was a Northrop Grumman plant, a massive white box sitting heavily along the west side of the boulevard. But with roughly 1,800 employees, SpaceX is significantly leaner than Northrop in its heyday.

"The people you see going into work [at SpaceX] don't look like people in the community," Pipkins said. "They didn't go to Crenshaw High, that's for sure."

The huge SpaceX warehouse on the corner of Crenshaw and Rocket Road, just south of Hawthorne Airport, looks much as it did when it was a Northrop Grumman plant.(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

The changes in Crenshaw's car culture have been even more dramatic. In the 1990s, the Los Angeles Police Department cracked down on the Sunday night cruising ritual, which barely exists now. More recently, African American teenagers, like teenagers across Southern California, have traded an obsession with cars for ones with smartphones and bicycles.

"Personally I don't really want to drive that much because I don't want to pay for gas," said Terry Monday, a 17-year-old high school student.

"Me and a couple of friends, we'd rather work on our fixies," he added, referring to customizable fixed-gear bikes that have become popular among L.A. teenagers, "or spend money on clothes or on our phones."

At dusk on a recent Sunday evening, it was easy to see evidence of the shift. At the corner of Crenshaw and Imperial Highway, a gleaming burgundy Chevrolet Impala convertible carrying three middle-aged African Americans idled at a red light.

Before the light could turn, a half-dozen African American and Latino teenagers passed by on their bikes, some of which were as carefully polished as the Impala. Three more teenagers on fully detailed bikes went by, then another four, laughing as they raced east into the darkness.

The notion has long persisted that Crenshaw Boulevard, despite its central location, stands isolated from the rest of Los Angeles. The street has been called the city's "forgotten spine."

The Hawthorne Municipal Airport on Crenshaw Boulevard covers 80 acres along the Century Freeway. Northrop Aircraft Corp. used the site as a design, manufacturing and test center during World War II. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

That sense of estrangement has clear physical and architectural form. The Santa Monica Freeway, completed in 1964, has provided an imposing barrier between the Crenshaw district and wealthier sections of Los Angeles to the north. The same is true of architect Claud Beelman's massive Harbor Building, built in 1956 for J. Paul Getty's Tidewater Oil Co. at the spot where Crenshaw dead-ends at Wilshire.

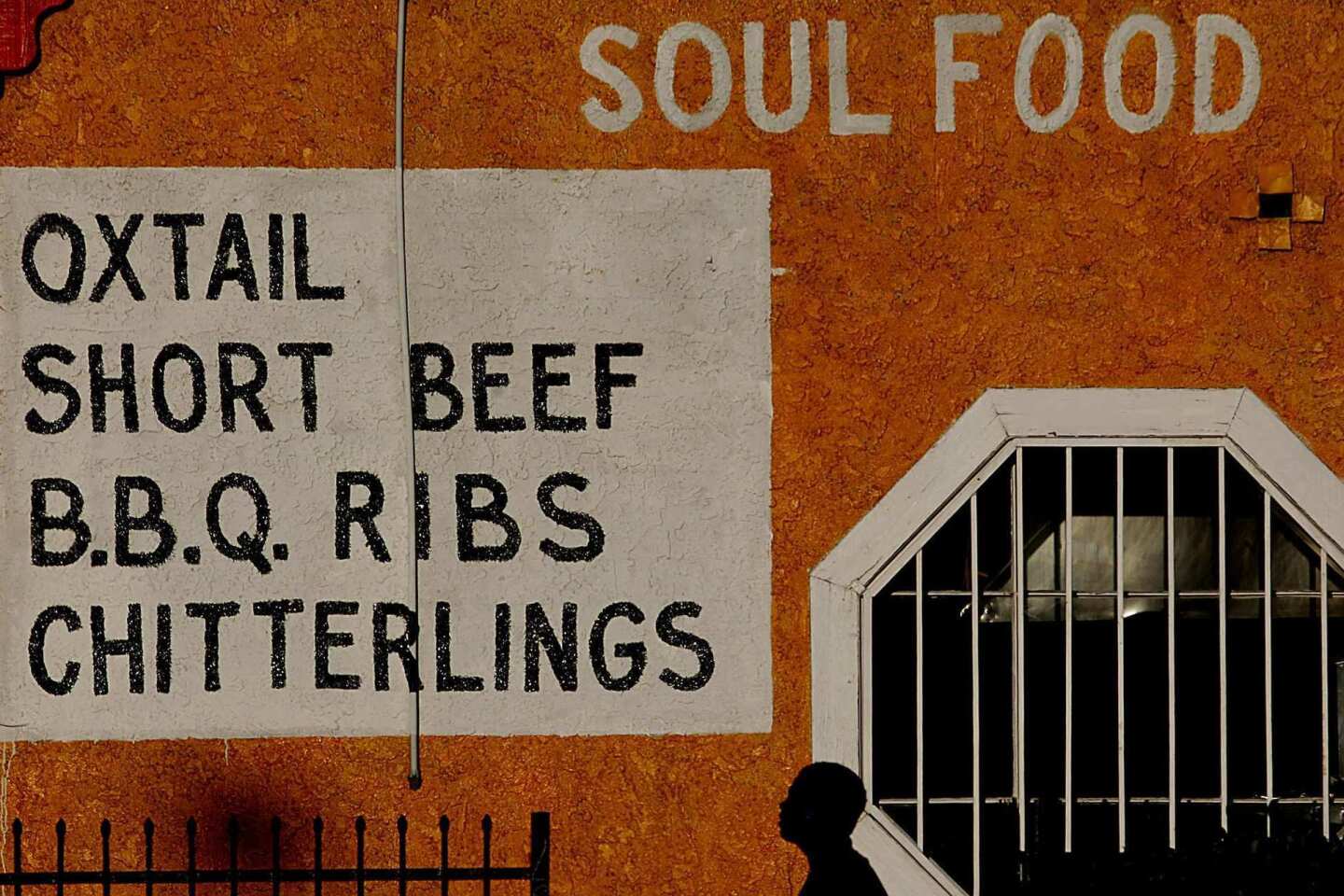

Crenshaw's isolation has had some benefits: It helped create a tight-knit community skilled at looking out for its own political interests. The cohesive nature of the Crenshaw district is reflected in the diverse architecture of the boulevard. It suggests a street that will take care of you from birth to death.

Albert C. Martin's streamlined Macy's building, built in 1947 for the May Co., is a centerpiece of the gigantic Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza. The Vision Theatre, an Art Deco triumph by Stiles O. Clements that overlooks Leimert Plaza Park, is owned and being restored by the city of Los Angeles. The gilded Angelus Funeral Home on Crenshaw near 39th Street was designed by Paul R. Williams, the preeminent black architect in Los Angeles for much of the 20th century.

Preserving some of these landmarks has been tricky. In the 1950s and '60s, the Holiday Bowl at Crenshaw and 37th Street was a multicultural gathering place owned by four Japanese American business partners. It was designed in the space-age Googie style by a team led by Helen Liu Fong, a talented young Chinese American architect at the firm Armet & Davis.

After the verdict in the Rodney G. King police beating trial in 1992, as parts of Los Angeles began to burn, there were reports of rioters who advanced on the bowling alley only to be met by a group of senior citizens and Holiday Bowl regulars -- both Japanese American and African American -- determined to protect it. The rioters turned back.

The alley closed in 2000, and when a developer threatened to tear it down to make room for a shopping center, preservationists helped broker a less-than-happy compromise: Holiday Bowl would be razed, but its coffee shop, facing Crenshaw, would survive.

The coffee shop, now a Starbucks, has a sawtooth roof that gives some indication of the architectural character that once marked the entire complex. But the way it meets the brick wall wrapping a new Walgreens to the rear is awkward, a symbol of a city still conflicted about its architectural history.

The coffee shop of the old Holiday Bowl is now home to a Starbucks, but the main bowling alley was razed and replaced by a Walgreens. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Less than a mile south, a $35-million upgrade of the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza has breathed new life into the huge complex. A Fresh & Easy market is planned for the corner of Crenshaw and 52nd Street, but Trader Joe's has yet to commit to a Crenshaw location, much to the frustration of local residents.

"We've had a hard time attracting the kind of retailers that other boulevards have been able to attract, because Crenshaw is still seen as the final dividing line between the poorer parts of South Los Angeles and the wealthier Westside," said Tunua Thrash, executive director of the West Angeles Community Development Corp., which is based at Crenshaw and 60th Street. "Crenshaw as a term, as a word -- 'The Shaw' -- has been a negative word."

Even in tough times, the Crenshaw district has maintained its status as a power base for black Los Angeles. Particularly in the residential neighborhoods in Baldwin Hills west of Crenshaw Boulevard -- upscale streets with wide views of the L.A. Basin that journalist Earl Ofari Hutchinson once called "the best advertisement for black achievement that you can find in America" -- you get a strong sense that this is the part of Southern California where black culture and the American Dream have come most comfortably together.

But it doesn't take much to stir up old insecurities and resentments. These days there is no subject that does so more reliably than the planned Crenshaw Line, which will run partially above ground and partially below from Exposition Boulevard south to Florence Avenue before bending west toward LAX.

Many residents and merchants are encouraged that rail service will return to the boulevard for the first time since the streetcar line was torn out in the 1950s. And the Metro board, chaired by Mayor Villaraigosa, hasn't ruled out a station in Leimert Park, calling it "optional."

But unless construction bids for the project come in lower than expected -- or Metro can find outside funding for the station -- the agency will build the Crenshaw Line without it.

Robert Ball, Metro's project director for the Crenshaw Line, said that it didn't make much sense to add a station in Leimert Park to one already planned a half-mile away at Crenshaw and Martin Luther King Jr. boulevards.

The 1939 Academy Theater, now the Academy Cathedral, is an Art Moderne structure located just off Crenshaw Boulevard and beneath a busy LAX flight path in Inglewood. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

He cited Metro projections showing potential ridership at Leimert Park "to be a little on the low side."

After watching the 10 Freeway cut them off from much of the city to the north, some Leimert Park residents now feel they're losing out again as Los Angeles builds rail lines instead of overpasses.

Simply in terms of ridership projections and population density, Metro officials may be right about a station in Leimert Park. But new train lines can also be a powerful mechanism for neighborhood revival along key sections of our most important boulevards -- parts of the city whose charms, architectural and otherwise, have been hiding for decades in plain sight.

Like many residential communities of its vintage in Los Angeles, Leimert Park was originally designed to take direct advantage of rail service. When Walter Leimert sold lots to potential buyers in the late 1920s, he boasted that his new subdivision was "15 minutes from downtown" on the streetcar.

It is hard to think of an area better positioned to benefit from the new vitality and foot traffic that a light-rail stop would bring. The neighborhood is compact, tree-lined and walkable and has a true public square at its heart: the 1-acre Leimert Park Plaza, designed between 1926 and '28 by the Olmsted Bros. firm, led by sons of the Central Park designer Frederick Law Olmsted.

We sometimes think of light-rail lines as a brand-new public amenity. But there are many parts of Southern California where rail is being reinstalled after a car-dominated interlude of 60 or 70 years. If you take a long view of Los Angeles history, you might conclude that it is the cars-and-cars-only era that will turn out to be the anomaly, the blip on the civic timeline.

What the champions of the Leimert Park station argue -- and what Metro officials so far seem reluctant to hear -- is that the return of rail service isn't just a means of giving this struggling neighborhood a boost. In a certain sense, it's a way to make it whole again.

Explore: Atlantic Boulevard and Sunset Boulevard with Christopher Hawthorne Los Angeles Times Architecture Critic.

Graphic credits: Lorena Iñiguez Elebee | Programming: Anthony Pesce

Sources: ESRI, TeleAtlas

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.