Deadly overdoses stopped surging among L.A. County homeless people. Narcan could be why

Year after year, Los Angeles County has seen devastating losses on its streets as homeless people bedding down in tents, under tarps and on sidewalks died of drug overdoses at soaring rates.

Now a newly released report shows that the death rate from overdoses stopped rising among unhoused people in the county in 2022 — the year L.A. County was stepping up its efforts to save lives.

Public health officials welcomed the news as a glint of hope, but cautioned it is too soon to say if the numbers are headed for a lasting downturn. They pointed to a county push to dramatically ramp up the distribution of naloxone — a medicine that bystanders can use to stop opioid overdoses — as a likely factor.

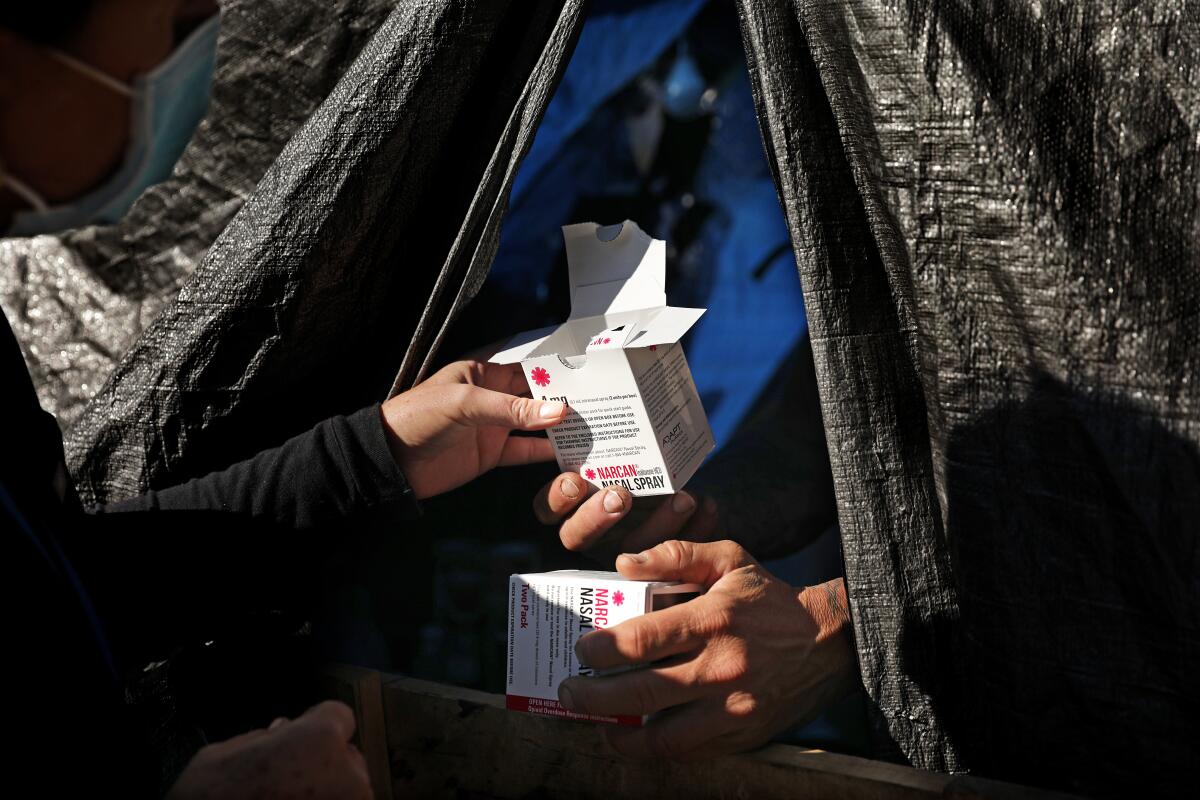

In their report, county officials touted a “near doubling” that year in the reported number of overdoses that were thwarted with naloxone, based on figures provided by a county program. The lifesaving medicine is commonly sold as a nasal spray under the brand name Narcan.

“We are cautiously optimistic here,” said Will Nicholas, director of the Center for Health Impact Evaluation at the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

“One year does not yet represent a trend, and the mortality rate is still unacceptably high, but it is good to see a plateau,” he added during a Thursday news conference.

“In the future, our goal is to start to see that curve turning downward.”

Two years ago in North Hollywood, Manny Placeres told The Times he had revived people seven times using Narcan that had been provided to him by a county team, honing his technique with time.

“As they’re knocking on heaven’s door, I pull them back,” Placeres said.

The L.A. County Department of Health Services has handed out Narcan at homeless encampments, given it to community groups and county agencies and set up vending machines to dispense it for free to people leaving county jails.

The health services department said it had distributed more than 620,000 doses of naloxone since December 2019. That resulted in more than 25,000 reports of overdoses being stopped — and the true number is believed to be roughly five times higher, it said. More than 240,000 doses of the medication were handed out through its initiative in 2022 alone.

Community groups and syringe programs have bolstered such efforts by handing out their own supplies of free naloxone provided by the state.

“The county really does deserve some serious kudos for pumping out a great deal of naloxone into exactly the right places,” which means getting it into the hands of people at high risk of witnessing or experiencing an overdose, said Peter Davidson, an associate professor in the department of medicine at UC San Diego.

In addition, Davidson said that Angelenos who use drugs may have taken other steps to reduce their risk of overdose, such as smoking drugs instead of injecting them, or making sure they are not using drugs alone.

When fentanyl hits a drug market, “initially people are caught by surprise, and things go very badly,” Davidson said. Then “they sort of adjust to the fact that the drugs now look different and change their practices.”

Dr. Gary Tsai, director of the public health department’s substance abuse prevention and control bureau, said that after years of alarming increases, “it is encouraging to see a slowing of this leading cause of death for people experiencing homelessness.”

“Efforts to increase access to naloxone and overdose prevention services have undoubtedly helped to bend this curve and provide a blueprint for reducing drug-related fatalities in this very high-risk population,” he said in a statement.

County officials said such efforts had also helped stabilize the death rate for homeless people overall after years of disturbing growth. As deadly overdoses stopped surging and COVID-19 deaths plunged, the overall mortality rate among unhoused people in L.A. County began to level off, the report found.

But homeless people remained far more likely than other county residents to die in a range of ways, including overdoses, traffic collisions, heart disease and homicide.

Their death rate overall was nearly four times higher than that of the broader population — a gap that has widened over time, public health officials found. And although it may have finally hit a plateau, the mortality rate for homeless people in L.A. County was still 60% higher than it had been three years earlier.

“The continued gaps in health outcomes across the board for those housed and unhoused reminds us that people experiencing homelessness in our county lack the very basic resources and conditions that are essential for health and well-being,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said Thursday.

The county report also pointed out some startling variations in the overall trends in L.A. County: For Black people who were unhoused, for instance, the rate of overdose deaths continued to rise significantly in 2022.

Public officials said the reason for the discrepancy is unknown and warrants further investigation. USC sociologist Ricky Bluthenthal said the diverging trends may reflect differences in when Black people locally began to face greater exposure to fentanyl in the drug supply, as well as possible gaps in Narcan distribution.

In the past, he and other researchers found that among people who injected drugs in L.A. and San Francisco, Black people were less likely to have received naloxone.

“We’re still learning how to saturate communities with sufficient naloxone to prevent ongoing increases in deaths,” Bluthenthal said. He added that “the city is still pretty segregated,” so there may be “concentrations of African American communities that have less robust access” to Narcan.

The rate of fatal overdoses also kept rising among homeless people in their 20s and 40s, the report found. That was offset by dropping rates among older people, but the report raised a grim possibility: After so many deadly years, “there may now be fewer surviving fentanyl and other opioid users over 50.”

Narcan can stop overdoses from opioids such as fentanyl, a powerful synthetic drug that has been involved in a rising share of overdose deaths among homeless people in L.A. County.

As Los Angeles has been devastated by rising numbers of overdose deaths, a local nonprofit decided to hit the streets to stop them, armed with cylinders of oxygen.

But fentanyl has not been the only threat: Roughly two-thirds of deadly overdoses among unhoused people involved more than one drug. Among the most commonly mingled were fentanyl and methamphetamine, a combination involved in nearly half of overdose deaths among homeless people in the county in 2022, according to the new report.

L.A. County public health officials called for a number of steps to bring down deaths among unhoused people, including expanding housing options so that people who use drugs will not lose their housing as a result; handing out more naloxone and test strips that detect fentanyl; and expanding preventative care for people who are homeless.

Veronica Lewis, director of the Homeless Outreach Program Integrated Care System, one of the largest service agencies in L.A. County, expressed enthusiasm about the recommendations, crediting the flattening of overdose and other deaths to concerted efforts to bring them down.

“Where there were plateaus, it was directly related to strategic and intentional responses,” Lewis said of the recent findings.

Lewis advocated for the “housing first” approach to homelessness, which prioritizes getting people into permanent housing quickly and removing barriers to entry. “Allowing people to get off the street first — and we address everything else next — is critical to even further reduce some of these deaths,” she said.

Ferrer said that “each life lost needs to be a call to action — for all of us.”

A Los Angeles County initiative called Reaching the 95% aims to engage with more people than the fraction of Angelenos already getting addiction treatment.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.