The Los Angeles mayor’s race has been defined by candidates’ sweeping promises to get homeless people off the streets — with the most ambitious talk coming from the top two finishers in the June primary.

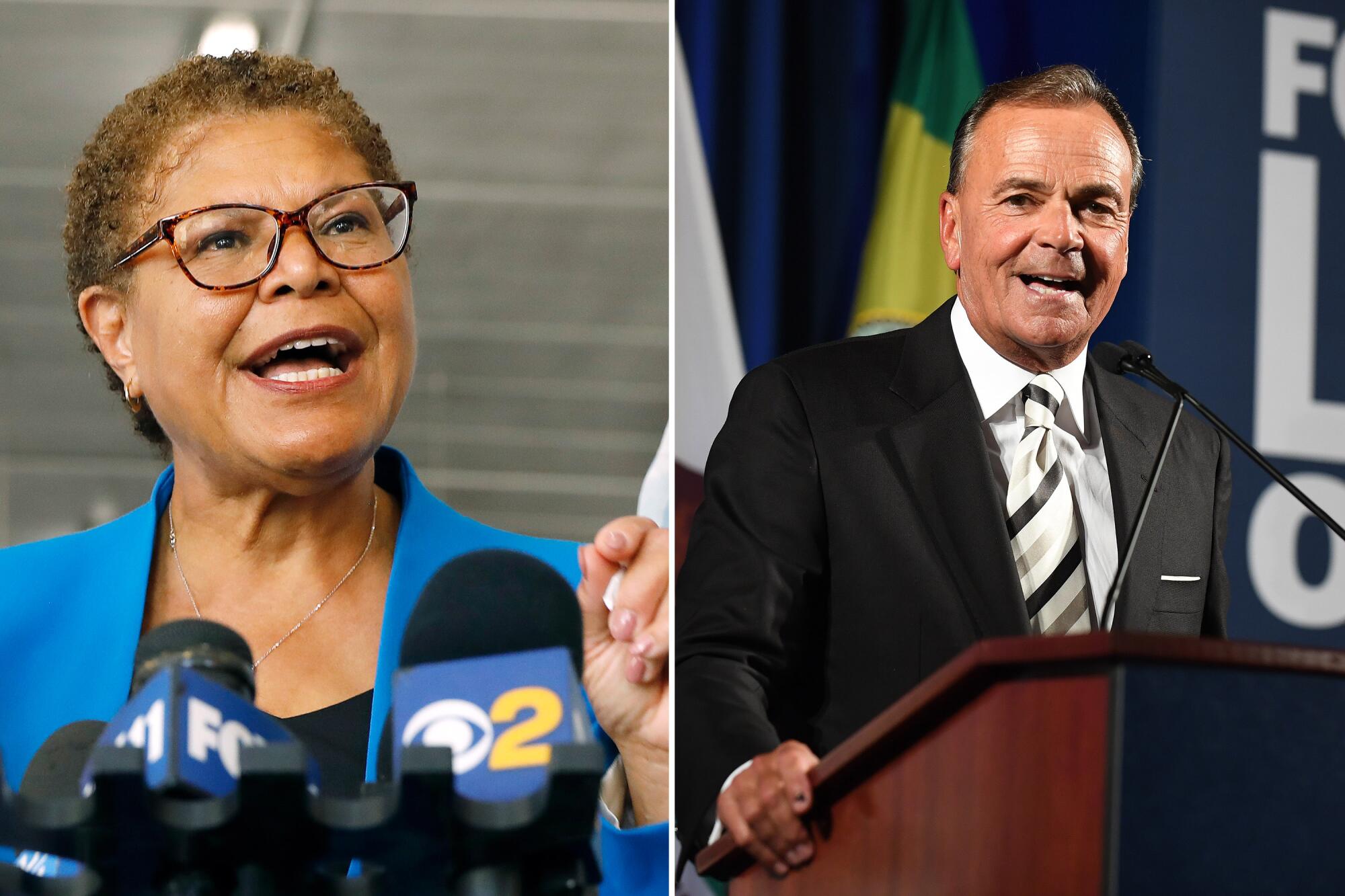

Rep. Karen Bass, who leads developer Rick Caruso in polls, said she would place 15,000 people in tiny homes, motels, hotels, apartments and other forms of shelter or permanent housing. Caruso went even bigger, saying he would create 30,000 new shelter beds in his first year in office.

But throughout the spring, in advance of the primary, neither candidate offered many specifics on the type of housing they would create, where it would be placed or how much it would cost.

Now, with the general election a little more than two months away, Bass and Caruso have provided the clearest glimpse yet into their respective plans, which take radically divergent approaches to addressing the homelessness crisis.

Caruso is firmly focused on construction of new interim housing, laying out an enormously expensive plan to build enough temporary housing units — in the form of tiny houses placed on 300 underutilized government parcels — to temporarily shelter 15,000 people. Another 15,000 people would find temporary shelter in “sleeping pods” placed in existing structures, such as warehouses and empty buildings.

Caruso estimated it would cost up to $843 million in the first year to build or acquire the housing and prepare it for occupancy. He declined to estimate the operating expenses for housing 30,000 people, but a Times analysis of city documents found that it would cost about $660 million a year, or about $22,000 per person.

Caruso wants thousands of tiny homes and ‘sleeping pods.’ Bass proposes some interim units, while pushing to expand vouchers, motel rooms, apartments and incentives to landlords.

“I would judge me on an every-30-day basis and I can lay out a timesheet for you, if you want me to because I like being held accountable,” Caruso said. “I’ve built my whole career against a schedule and a budget. Every project has a schedule and a budget.”

Bass wants to wring as much as possible out of the current system in order to expand both interim and permanent housing, though at a far smaller scale than Caruso envisions.

She would build new shelter beds to accommodate about 1,000 people. Bass’ plan also relies on expanded use of housing vouchers, the leasing and purchase of motels and hotels, and other approaches.

Bass has upped her early target — and now plans to bring a little more than 17,000 people indoors — by cobbling incremental improvements in several existing programs, including 1,500 veterans’ housing vouchers she added after an interview for this article.

Her plan estimates a first-year cost of $292 million, including construction costs and operating expenses for shelter beds.

“You have to have different housing, depending on what we’re talking about,” Bass said. “If you’re chronically mentally ill, you need different housing. But you know what, at the end of it, we also have to look at jobs and moving people from permanent supportive housing into the mainstream.”

The costs in Bass’ plan broadly hew to what the city has spent on a variety of permanent and interim housing options in recent years. Still, she said she’d find ways to build more cheaply.

It’s a very different picture from the spring, when political tailwinds and near-unlimited funding fueled Caruso’s ascent.

Caruso pushed back on The Times’ cost estimates, saying he could significantly expand the supply of beds for homeless people far more cheaply than has been done in the past. In any case, they both argued, it was the county’s obligation to operate the housing, not the city’s.

Their plans elicited a mix of praise and skepticism from current and former elected officials who have addressed the homelessness crisis while in office.

“I don’t think either of those plans will accomplish what they say they are going to accomplish in a year,” said Zev Yaroslavsky, director of the Los Angeles Initiative at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs and a former city councilman and county supervisor. “I just don’t think it’s possible. But I think it’s good to set the goal, [but] a plan is just a plan until you execute it.”

Get the lowdown on L.A. politics

Sign up for our L.A. City Hall newsletter to get weekly insights, scoops and analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Yaroslavsky said he sees strong elements in both plans — and hopes the winner will crib from his or her opponent — but thinks the new mayor can succeed only by overcoming the political fragmentation and rivalry that confound good plans.

His solution is a single, countywide homelessness executive ceded power by the supervisors and the county’s largest cities to budget money and make land-use decisions.

“The city and the county have to come to the mountain,” said Yaroslavsky, who has not made an endorsement in the race. “Let the city and the county create a new paradigm, set a new template of political collaboration and cooperation and effectiveness.”

Activists and some politicians have emphasized that homeless people living in interim housing remain homeless. The city, they say, would be better served devoting more resources to preventing people from falling into homelessness and helping people get permanent housing, rather than building thousands of shelter beds.

“What happens to the people who are using those interim resources if there’s not enough affordable housing to go around? This can’t be the end of the solution,” said Ann Marie Oliva, chief executive of the National Alliance to End Homelessness, who previously helped advise the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. “How are we going to get to the affordable housing scale that’s needed in Los Angeles?”

Where would the money come from?

Both plans envision spending hundreds of millions of dollars beyond what the city and county already spend each year on homeless housing and services — money largely coming from two ballot measures approved by voters several years ago, augmented by state and federal funds.

The candidates say they can meet these additional costs by securing more federal and state dollars, by reining in construction costs and by running the city and its homelessness programs more efficiently.

As things stand now, the city budgeted about $1 billion on homelessness, the largest share of it on building and operating permanent housing, not on the interim approaches proposed by both candidates.

For Caruso, the city’s past spending on budgets for shelters was bloated and could be drastically reduced. Bass’ plan leverages state and federal resources that hold down the city’s cost, as does Caruso.

Both candidates asserted they can make city government move faster, with Caruso touting his experience in building large projects in the city and Bass with her knowledge of government and relationships in Sacramento and Washington.

Promises in both plans to put interim housing on government land illustrate key differences between them, in scale and character.

Caruso leans on new construction

After visiting tiny home communities and modular housing manufacturers in Las Vegas and Oakland, Caruso and his staff said they are convinced it is possible to put about 15,000 tiny-home-style shelter beds, or half his goal, on some 300 unused government properties the campaign has identified. It provided a list of 10 examples, including a 124-acre parcel west of Los Angeles International Airport destined to become a rental car center, and a vacant lot west of USC.

Bass would use government land for only 1,000 interim beds. Her advisors said they would be equally divided among tiny homes, modular structures and tent shelters like those the city has recently installed in several locations and would cost about $75,000 each, covering both construction and services for the first year of operation.

Still, she expressed qualms about the tiny homes that are the mainstay of Caruso’s plan.

“My immediate reaction to tiny homes was safety, especially for women,” Bass said in an interview. “That worried me when I went to the tiny home village, especially at nighttime.”

Caruso’s advisors said that construction, site preparation and building upgrades would cost about $47,000 per tiny home, far less than the roughly $80,000 average cost the city has incurred for the more than 700 it has built. Caruso and his staff said the actual cost could be as low as $20,000 to $25,000 but would not commit to a minimum figure without access to more data held by the city.

Promises for housing people in tiny homes, as well as the cost, cannot be easily compared because of uncertainty over how many people will occupy each home. The 8-foot-by-8-foot structures purchased by the city have two beds but, due to pandemic restrictions, have generally been occupied by only one person. The city is now experimenting with double occupancy, but it is unclear how extensive the practice will be.

Caruso said he would allow people, such as couples, to share a tiny home but would not require occupants to have a roommate if they did not want one. Bass’ staff counts each tiny home in her plan as two beds, saying they believe they all can be filled with couples.

When it comes to finding locations for these tiny home communities or any other form of shelter, Caruso said he’d be far less deferential to individual City Council members on land-use decisions.

“There should not be 15 separate council districts, doing things 15 separate ways,” he said, calling it a “very inefficient waste of taxpayers’ money and doing that, taking way too long to get done.”

Costs also could be slashed by eliminating unnecessary features that city bureaucrats pile on construction plans, he said, pointing to concessions that Councilman Kevin de León extracted from the Fire Department to lower the cost of the 224-bed tiny home village in Highland Park to about $59,000 per home.

According to De León, among the items he rejected was a $2,000 internet-connected smoke detector for each tiny home.

Caruso’s plan also calls for installing 15,000 semiprivate “sleeping pods” in underutilized commercial and residential buildings. He and his advisors estimate that the low-maintenance, collapsible units with walls enclosing each bed would cost $4,740 each and that only modest renovations would be required in buildings already connected to utilities.

They estimate the tiny homes and pods combined would cost $743 million to $843 million, less than half the city’s historical cost for that many beds.

Bass would bolster current programs

Bass, by contrast, spread her goal over nine programs that she estimated would cost the city $292 million.

The congresswoman said she would eliminate restrictive eligibility rules and onerous applications that have blocked the use of more than 90% of the emergency housing vouchers the city received from the federal government, getting 3,170 people quickly into housing.

Bass also said she would expand landlord incentive programs to make it easier for voucher-holders to find apartments.

She promised to remove red tape to speed construction under Proposition HHH, the 2016 city bond measure, which has been beset by rising costs and long delays. The 3,000 units of permanent supportive housing she credits to her plan is fewer than it sounds; 2,000 of those units are already in the pipeline and scheduled for completion in the next mayor’s first year.

A quarter of the promised placements — making up the largest chunk of her plan — would not be in new beds. Bass counts as placements the 3,700 beds that would become available by freeing space in existing interim housing when those residents move into the new permanent housing in her plan.

A new round of the state-funded Project Homekey purchases would bring in 700 hotel and motel units on top of the roughly 1,700 units the city has already bought over the last two years. (The city’s matching cost would be $105 million, Bass said.)

Bass said she would add 2,500 beds by committing $30 million to lease entire apartment buildings or motels, allowing the city to include services such as dining and treatment for mental health and substance abuse.

Expansion of the city’s downtown adaptive reuse ordinance to the entire city would produce 500 new units by converting commercial buildings to housing, Bass said.

The final piece of her plan would pave the way for 750 new mental health and substance use beds by eliminating a long-standing federal policy that prohibits Medicaid dollars from being used at mental health facilities with more than 16 beds. Bass said she is working with Gov. Gavin Newsom to obtain a waiver from the outdated policy.

Then, Bass said, “places like the 344-bed St. Vincent Medical Center, which is empty and being used as a filming location, can be converted into treatment centers” with complete care from stabilization to long-term housing.

Los Angeles Times owner Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong purchased the shuttered hospital in 2020. In response to pleas to make it available, he has said he is willing to discuss its future use with the city.

De León, who has not endorsed a candidate in the runoff after his own mayoral campaign fell short in June, found both proposals lacking.

“Rick’s plan of 30,000 is unrealistic, because 30,000 means SoFi or Crypto.com, or the Coliseum or Dodger Stadium is going to open up their field and you can put cots out there,” he said. “That’s how you move massive numbers like that and we know through experience, congregate shelter — [homeless people] don’t like it,” De León said.

De León, who has called on the city to build 25,000 new temporary and permanent homeless housing units in the next five years, called Bass’ plan “unambitious.”

“Karen’s plan is going to happen period,” he added. “It’s akin to getting in front of the parade.”

Banking on greater efficiency

Both candidates said they would declare a state of emergency on their first day in office to cut through bureaucracy and that they would demand improved performance from city department heads.

Both declined, for now, to endorse a proposed special tax on real estate transactions set to appear on the fall city ballot, or renewal of the countywide Measure H sales tax that funds the bulk of the services in city shelters and housing.

“I believe that before we would ask for that, we have to demonstrate what we’ve done,” Bass said.

“To be honest, we better figure out how we spend money wisely, taxpayer dollars wisely, before we take any more taxpayer dollars,” Caruso said.

On the philosophical divisions that dominate public discourse on homelessness, their differences were more over style than content.

They both supported the City Council’s decision to ban homeless camping near schools.

“I don’t accept the idea that the way we solve the problem is by moving people around,” Bass said. But, recalling the sight of a block-long encampment near the Barack Obama Global Preparation Academy on Western Avenue, she added, “I do think that, you know, you have to move that situation.”

More explicitly, Caruso said the new ordinance was a “no-brainer.”

“How could anybody vote to having encampments near school?” he asked.

Bass, a former physician assistant who made foster care reform a focus of her work in Congress, spoke emotionally of the need for specialized housing and supervision for youths exiting that system.

She also called for a better safety net for people leaving prison, saying they are rendered homeless because “they can’t get a job, they can’t rent an apartment and they might not even be able to go home if their families have members that are felons.”

For Caruso, the goal of a massive expansion of interim housing derives from a belief that the multiple social, economic and health problems of people living on the streets can be addressed only once they’re indoors. He also spoke of his respect for homeless people’s need for community.

“We need to build a community that actually the homeless can be proud to live in, not that they’re just sheltered there,” he said. “So we need to have a mayor that’s got a vision of creating a place that will be comfortable and welcoming.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.