Formerly homeless motel residents were kicked out — to make room for L.A.’s homeless

The owner was a willing seller, and Los Angeles County an eager buyer. Escrow was set to close Tuesday on what would have been the county’s 10th purchase under a state program to convert hotels and motels that are ailing because of the COVID-19 pandemic into housing for homeless people.

Then the good news story turned messy when activists, including lawyers representing some of the motel occupants, came to the county Friday with a shocking complaint: The management of the extended-stay Studio 6 motel in Commerce was locking out residents who had lived there for months or even years, forcing some into homelessness without the relocation benefits they were entitled to under state law.

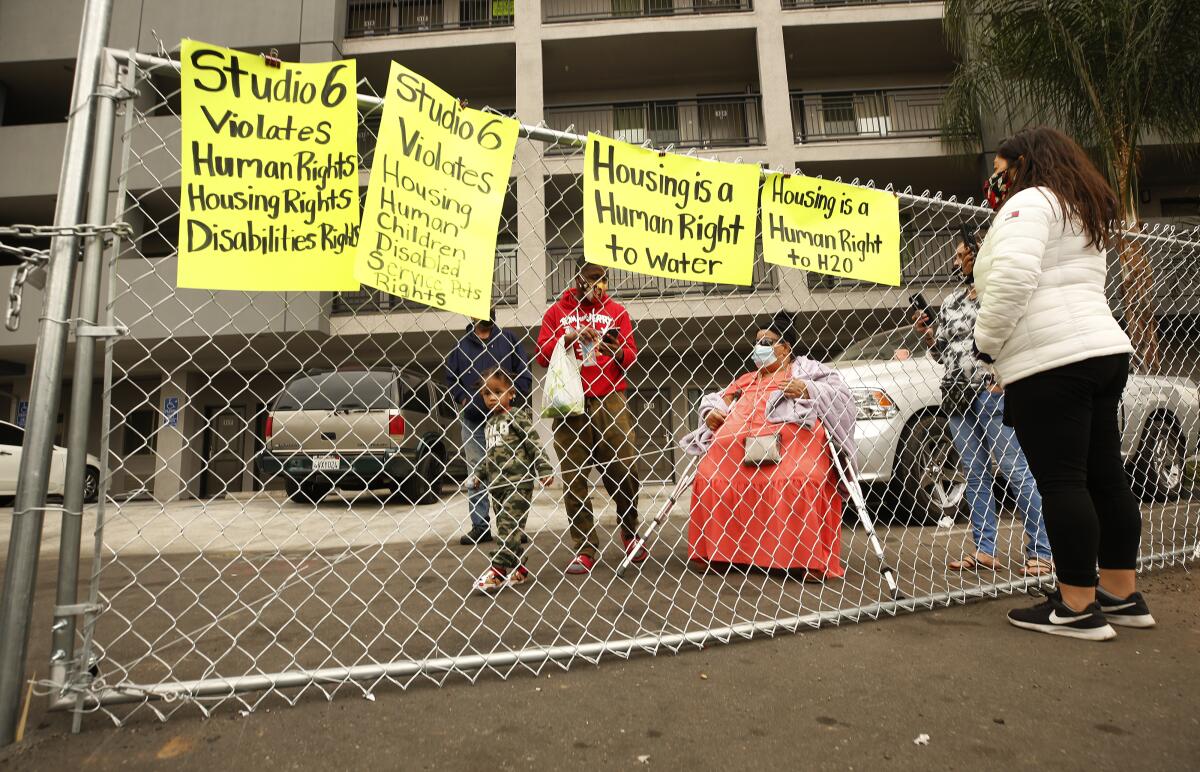

The situation grew contentious over the weekend as activists gathered at the entrance in support of about a dozen remaining residents and the management installed a locked fence across the narrow driveway to the parking lot to keep them out.

This week, activists continued their vigil outside the fence, shouting support for the residents, who included a single mother with three children and a three-generation family with a disabled grandmother who said she spent three days in her car after being locked out.

Caught off guard by the blowup, the county pushed the close of escrow to Dec. 17 and sent its relocation consultant back to the motel to determine whether any occupants had established legal tenancy and were unlawfully evicted and denied relocation payments.

Terms of the sale require the owner to deliver the building without occupants, and any relocation benefits owed would be paid by the county, officials said.

A front-desk worker who answered the phone at the motel said the manager, identified by residents as a Mr. Patel, was not available. But the worker, Harry Bacta, denied that any guests had lived in the motel as permanent residents. He said all were notified when they checked in that Dec. 3 would be their last day.

“Some of them are like regular guests who leave and come back from time to time.” Bacta said. “None of them are long-term guests.”

County officials said they worked furiously over the weekend to stabilize the situation but have not yet determined how many, if any, of the occupants have tenants’ rights.

“We’re currently working in a collaborative manner with the advocacy organizations who became aware of the situation to ensure that no one is displaced from the hotel into homelessness and to ensure anyone who does have tenant status is accorded all the rights and benefits to which they are entitled,” said Phil Ansell, director of the county’s Homeless Initiative.

The tenant relocation consultant, OPC, is interviewing hotel occupants and others who claim tenancy.

The relocation consultant determined in its initial assessment that only the on-site manager qualified for tenancy. During contract negotiations, the county was led by the owner to believe that there were no guests who have stayed close to 30 days, Ansell said.

Several residents told The Times that they had been paying rent regularly, either from their own resources or with government rental assistance.

They said the manager would not provide them receipts and frequently levied unfair fines.

The question of who qualifies as a tenant could hinge on a nuance of state law. If a person lives somewhere longer than 30 days, he or she is considered a tenant with a litany of rights afforded through state and federal law, including eviction protections, said Navneet Grewal, a lawyer for Disability Rights California who has been helping some of the people staying in the Studio 6. Often, she said, residential motels will force people to leave just before they hit 30 days so they don’t qualify for protections.

This is sometimes referred to as the “28-day shuffle” and is banned by state law, she said.

In a bid to get homeless veterans off the streets, Los Angeles awarded more than $10 million to help transform an unfussy building in Westlake into supportive housing.

Many hotels and motels are used by social services agencies to house some of the county’s poorest and most vulnerable — some of whom receive vouchers to subsidize their stay. The rooms are a lifeline for many who would otherwise be on the street.

Several of the residents said they had well-established residency in the building.

“I moved here [in] August of 2019,” Genevieve Marilyn Green said. “I get mail here.”

Green shares a unit with three infant and toddler children with rental assistance through L.A. County’s Family Solutions program.

She said she was working with a homeless agency to find permanent housing but had to turn down a new home to quarantine after she contracted the coronavirus.

“We were supposed to be here two or three months, and we were supposed to be housed,” said Mikki Morris, 65, who lives with two sons, one severely disabled, and gets around on a walker. “The pandemic made that impossible. We were stuck here.”

Morris said the management manipulated and intimidated many of the more than 30 families once living there to leave.

“We were lied to, manipulated, bamboozled, everything you can imagine,” she said.

Hope Golden, 55, who steadies herself with crutches, said she, her daughter and son-in-law and their 2-year-old son receive no rental assistance and were current with their rent.

But when she came back from the bank on Nov. 30, she was locked out of her room and her personal belongings were gone.

She said she made a police report and slept three nights in her car in the parking lot.

“I don’t got nowhere to go,” said her son-in-law, Amis Streeter, who said he lost his job at Universal City because of the pandemic. “I need my stuff. They cleared all my stuff out. I don’t know where it’s at.”

Lucia Veloz, 40, had worked as a housekeeper at the motel since 2018, but was let go in October after injuring her back. She recalled meeting families, some of whom had lived there as long as three years, packed into small rooms as a last resort. Every month, they were told by management they had to leave for at least a day. That was when Veloz cleaned their rooms.

“A lot of these families, they don’t have anywhere to go. That’s why they’re there to begin with,” she said in Spanish. “I feel terrible because they lost their home and I lost my job.”

Veloz is now struggling like these families — on government assistance and unsure how she’ll pay the bills. She’s still out of work and recovering from COVID-19, which sickened several members of her family.

Heidi Marston, who heads the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, said this issue came onto her team’s radar late Friday night when county officials reached out for help finding some of the displaced people places to stay. They were told about two people and a family were staying in the parking lot and needed help.

They were able to get the family into a motel.

After reaching less than 30% of its goal to shelter homeless people who are vulnerable to the coronavirus, Project Roomkey is starting to phase out in the face of funding uncertainty.

L.A. County is paying $14.95 million for the four-story, 81-room motel. It stands next to a gas station on a noisy triangle of land wedged between the 5 Freeway and East Slauson Avenue, a busy truck route.

When the sale closes, it will be the 10th building purchased by the county under Project Homekey, a state program providing funds for cities and counties to quickly house thousands of homeless people by purchasing motels and hotels that are financially weakened by the pandemic.

The city of Los Angeles is purchasing an additional 10 hotels under the same program.

Two of the hotels in the county are currently under lease to Project Roomkey, another state program to provide temporary housing for homeless people during the pandemic.

The Studio 6, owned by a company called Anmol, was not a participant in Project Roomkey.

“It’s just ironic that they’re creating homelessness when implementing this program that’s supposed to take people off the streets,” said Jasmine Gonzalez, an organizer for East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice. She has been helping some of the families at the Commerce motel.

“It’s a lack of communication. It’s just incredible that this is happening.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.