Despite protections, landlords seek to evict tenants in Black and Latino areas of South L.A.

Despite new anti-eviction rules passed in response to the novel coronavirus outbreak, some Los Angeles landlords are still trying to oust tenants by locking them out of their homes, turning off their utilities and deploying other illegal methods, a Times analysis of data from the Los Angeles Police Department has found.

In the initial 10 weeks after L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti ordered a temporary moratorium on evictions in mid-March, police responded to more than 290 instances of potential illegal lockouts and utility shutoffs across the city, according to the data.

The Times analysis shows that the largest share of those police calls was in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods in South L.A. such as Vermont Square, Florence and Watts — the same communities that have faced the greatest health and economic problems from the coronavirus.

South L.A. neighborhoods have some of the county’s highest rates of coronavirus infections. Residents there also faced disproportionately high rent burdens even before the pandemic and often work in food service and other sectors with significant wage and job losses due to COVID-19, according to a recent study by UCLA’s Center For Neighborhood Knowledge. And because of the large population of undocumented immigrants, many cannot receive unemployment benefits or other government assistance.

“This is a web of urban inequality,” said Paul Ong, an urban planning professor emeritus at UCLA and author of the study. “We could talk about housing, we could talk about jobs, we could talk about health. But the truth of the matter is all these things are interlocked.”

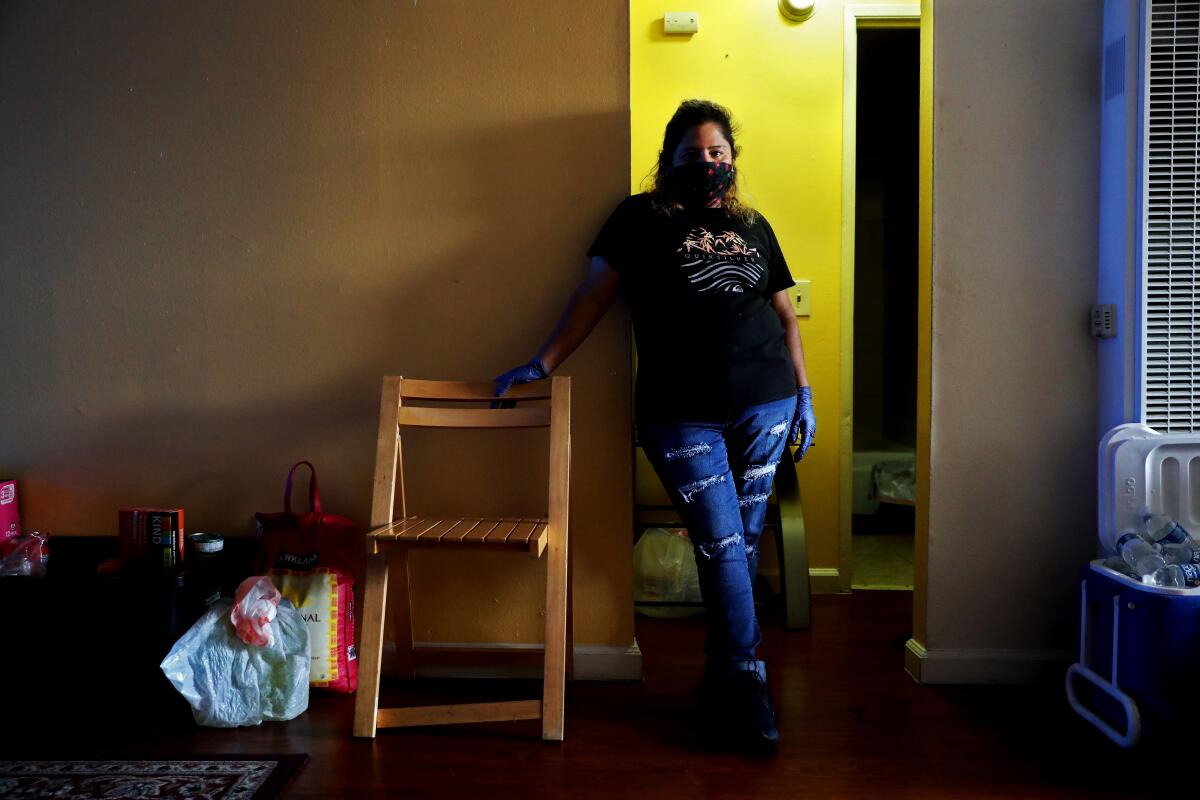

Weeks into the pandemic, Claudia Mendez was facing many such problems. She was running short of jobs cleaning houses and the rent was coming due when she contracted the coronavirus.

Stuck in her South L.A. apartment, Mendez was spared from going hungry by friendly neighbors who left food by the door.

But one morning in late May, Mendez awoke to find a woman who identified herself as the landlord in her apartment’s living room. Mendez said she had been subleasing the place for three years from her roommate, an arrangement that now seemed to catch the landlord by surprise. Since that roommate was leaving, the landlord said, Mendez had to go too.

Soon afterward, the landlord cut off the utilities, packed Mendez’s clothes and other belongings into trash bags and plastic tubs and hauled them outside. The landlord even removed the toilet from the bathroom, said Mendez.

After a day of uncertainty — and after protesters from the Los Angeles Tenants Union descended on her home — the landlord relented. A contractor who had watched the situation unfold on Facebook came and reinstalled the toilet. Mendez remains in the apartment, for now.

“I didn’t sleep. The situation was very difficult,” said Mendez, 42. “I’m not at peace because I’m afraid the police can come evict me from here.”

The property’s owner is listed as Coldwater Canyon Trust, which is located in Beverly Hills. Representatives did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Even under normal circumstances, landlords cannot evict tenants by themselves. Instead, landlords must file an unlawful-detainer case in court against a tenant who hasn’t paid rent or has otherwise violated their lease terms. Currently, however, nearly all evictions in California are on hold because the state court system is not processing cases except for those deemed emergencies.

Ultimately, if a landlord wins an eviction case, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department — not LAPD — carries it out. But LAPD does respond to calls from tenants who say they’ve been illegally locked out and to other conflicts between landlords and renters.

Such calls have increased during the pandemic. Through June 6, landlord-tenant disputes were up 17% on average, according to a Times analysis of LAPD call data before and after the mayor’s anti-eviction order.

The Times further analyzed a subset of the LAPD calls likely to involve potential efforts to evict tenants, such as those describing utility shutoffs or lockouts, after the city’s coronavirus tenant protections went into effect. More than a fifth of 292 incidents between March 16 and May 25 occurred in just two of LAPD’s 21 divisions — 77th Street and Southeast — which cover neighborhoods in South L.A.

Calls included complaints that landlords had shut off water and electricity services and removed tenants’ belongings in an effort to force them out. Officers have sometimes responded to concerns at the same residence on multiple occasions.

Landlords say the economic slowdown from the pandemic has placed many in their own financial bind. Although they’re encouraged to work with tenants on repayment plans for overdue rent and to make other accommodations, landlords may have their own troubles with mortgage payments and other bills.

Dan Yukelson, executive director of the Apartment Assn. of Greater Los Angeles, said he’s upset when he hears about any cases of landlords illegally locking out tenants and that he’d kick such offenders out of his organization.

Nevertheless, Yukelson said that landlords are struggling under the proliferation of anti-eviction rules. The association has sued the city of Los Angeles, arguing that its eviction protections — which could require landlords to wait for more than a year after rent was due to collect — are unconstitutional and causing widespread economic and property damage.

“People feel like their backs are against the wall today,” Yukelson said. “There’s really no maneuverability. [Landlords] have absolutely nothing, no tools at their disposal when someone doesn’t pay.”

George Wimberly, a 92-year-old disabled World War II veteran, said he feared falling behind on his own bills when the tenant living in a small back house on his property in the Florence neighborhood of South L.A. stopped paying rent. Though he sympathized with other renters who have lost their jobs because of the pandemic, Wimberly thought his tenant should pay because he was receiving the same Social Security benefits as he did before.

So in early April Wimberly turned off his tenant’s electricity. Police arrived and Wimberly agreed to reconnect the power. The tenant, Wimberly said, has paid some back rent, but is still behind. If he could, Wimberly would evict his tenant right now.

“He’s still back there using my electricity and my gas,” Wimberly said.

Tenants facing illegal evictions increasingly seek help with the L.A. Tenants Union, which organizes protests outside apartments to block evictions. The group has seen a surge of incidents during the pandemic and they’ve been disproportionately located in South L.A., said Katrina Albright, an organizer with the tenants union’s South Central local.

“It’s just an absolute zero to 60 in terms of the uptick,” Albright said.

Albright was critical of police response to those cases as well. She said that officers favor landlords during the disputes, demanding to see tenants’ utility bills or treating incidents as trespassing, even though the law has prohibited evictions without a court order even before the pandemic.

“Knowing the law is not enough,” she said. “It takes a whole community of people to physically turn up to block these things with their bodies.”

Attorneys at two L.A. renter legal assistance organizations — Public Counsel and Eviction Defense Network — say they are reconsidering or have stopped advising their clients to call the police if threatened with an illegal eviction, saying that they’re losing faith in the department’s ability to protect tenants.

Gisselle Espinoza, an LAPD spokeswoman, said she was unaware of tenant groups’ concerns about how officers are handling landlord-tenant disputes, but that the department is always troubled if people believe police aren’t dealing with situations fairly.

“I strongly encourage the public to continue to call us,” Espinoza said. “We will respond and handle the investigation accordingly.”

Mendez, the house cleaner, remains worried about her future. She’s two months behind on rent. She no longer has a refrigerator and the landlord removed the sliding doors to the balcony, allowing mosquitoes and flies to come inside the apartment. Still, without work now or in the foreseeable future, Mendez is not sure where else to go.

“I can’t pay much rent because I don’t have anything right now,” she said. “In truth, I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.