First they needed to coax Fatima from her tent.

Outreach workers Ciara DeVozza and Jenna Kennedy knew that the 37-year-old homeless woman had a fever and chills. But Fatima insisted it was from the hole in her tooth, not the coronavirus. So DeVozza and Kennedy, looking to build trust and persuade her to get tested, told Fatima they might be able help her see a dentist.

Fatima, who is blind, agreed and was guided toward the center of an empty parking lot near 3rd and Main streets.

“I know, I know. I’m sorry,” said Shannon Fernando, a nurse practitioner with L.A. Christian Health Centers, as she stuck a long swab up Fatima’s nose. “Just count to 10 and you’ll be all done. Almost done. Almost done. You’re doing so good.”

Fatima teared up and waved her hands.

“I know it sucks,” Fernando said one recent morning. “So in 24 hours we’ll have results.”

As outbreaks large and small continue to pop up among L.A.’s most vulnerable residents on skid row, a small group of nurses and outreach workers have begun a manic quest to test as many homeless people as possible.

“We don’t know what we’re dealing with yet,” Fernando said. Until recently, “there has been no widespread testing.”

On Thursday, L.A. County Department of Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said 215 homeless people had tested positive for the virus and that the county was investigating cases at 18 shelters.

But even as Mayor Eric Garcetti has extended testing to everyone in L.A. County, regardless of symptoms, doing the same on skid row has proved to be far more challenging.

It’s about basic issues of logistics. People who live on the streets don’t stay in one place for very long, aren’t always easy to track down and don’t always have a working cellphone or an email address. So how do medical professionals and outreach workers find them to share test results? And what if a homeless person is positive and continues to spread the virus as they await results?

There are also issues of trust. Some homeless people are wary of outreach workers and their suggestions because of past promises for housing and services that have never materialized.

But nurses and outreach workers have resolved to do their best to conduct more tests, while also acknowledging that the lack of shelter beds and hotel rooms for homeless people has made limiting the spread of the coronavirus almost impossible.

“What do we have in L.A. County? There are 60,000 people who are considered homeless,” said Dr. Silvia Prieto, who is coordinating the response to outbreaks at shelters for the Department of Public Health. “Nobody has that many beds right now.”

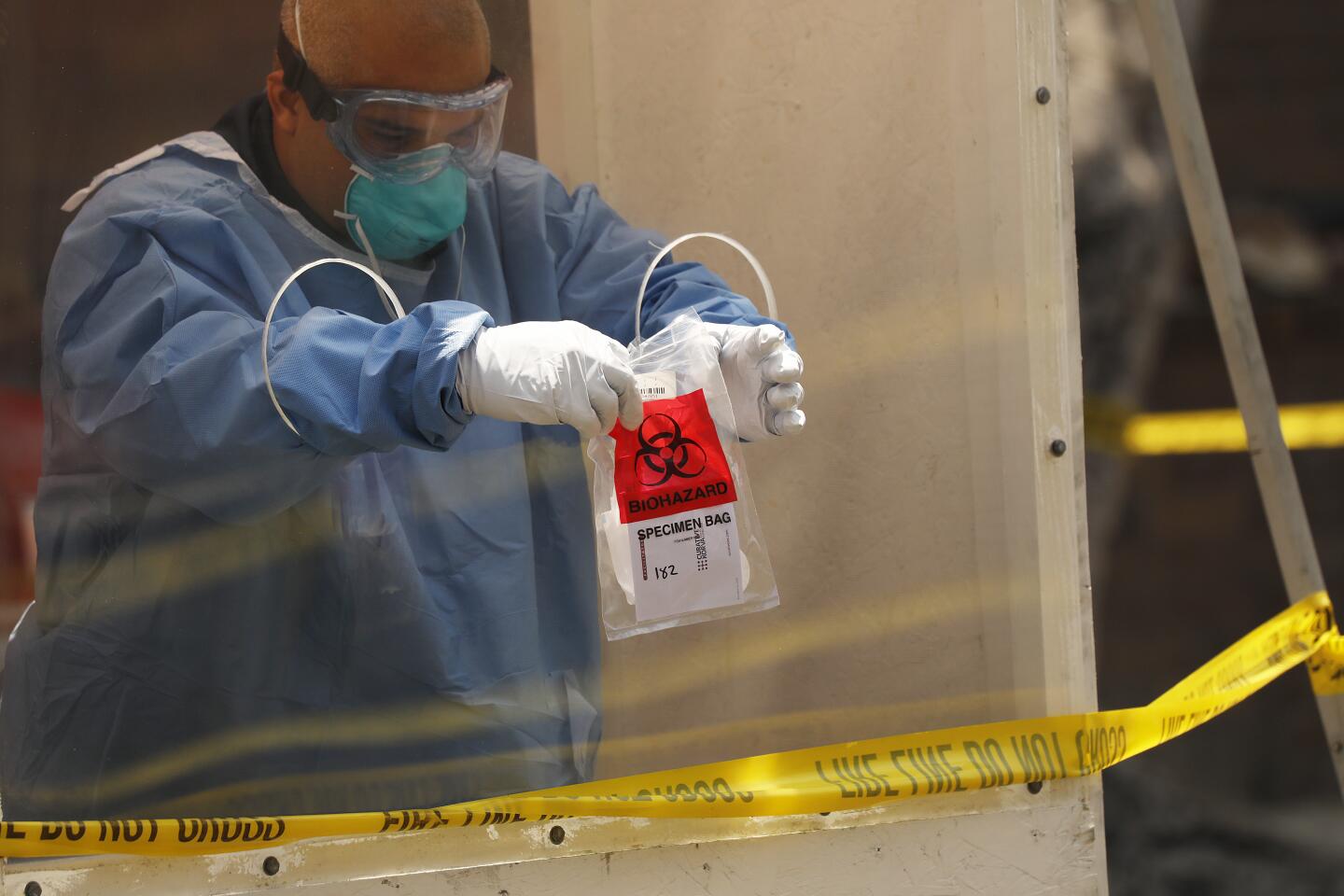

Several agencies are doing testing of homeless people. Among them is the Los Angeles Fire Department, which has set up a pop-up site on skid row, where the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority is encouraging people get an oral test. Getting results takes up to five days. More than 1,000 people — not all of them homeless — have been tested at the site since it opened April 20, a Garcetti spokeswoman said. Seven have tested positive.

L.A. Christian Health Centers, through a contract with the county, also has set up shop at the Midnight Mission and L.A. Mission to test residents. In addition, Fernando and another nurse with the center, Carolina Maradlaga-Esguerra, are working with the outreach teams to search encampments for people to test.

The same day the team tested Fatima, they tried to test many others. Among them was Kimberly Lockett, 61. Spindly and hunched over, she said she has been using heroin since the the 1980s.

“If I have a place to go to, I’ll get tested,” Lockett told DeVozza and Kennedy, as they promised to get her a hotel room and medication to ease her withdrawal from opiates. With other outreach workers, she told them, “I feel like I’m getting tricked.”

Getting a hotel room isn’t easy, though. The statewide program to move homeless people into hotels, known as Project Roomkey, has gotten off to a slow start in Los Angeles County.

DeVozza said workers have made more than a hundred referrals to the program and managed to get rooms for only three people. Instead, her nonprofit employer, The People Concern, has been renting rooms directly from hotel owners it has worked with in the past.

They got Lockett a room, but she still refused to take a coronavirus test.

Elsewhere in the encampment, DeVozza struck up a conversation with Amaya Caraveo-Jaime, who was standing, sweating amid a thicket of tents and people. The 20-year-old said she was feeling nauseous, but told DeVozza that she was hooked on fentanyl and was unsure if she was suffering the side effects of withdrawal.

DeVozza offered Caraveo-Jaime a dose of Narcan and a box to hold used needles. Then DeVozza explained that she could get her something to help with the withdrawal. A county-provided coronavirus isolation bed at a hotel could also be made available.

At first Caraveo-Jaime was game, but then she learned that once she entered, she couldn’t leave. Caraveo-Jaime wanted to know what would happen if she needed cigarettes and if her boyfriend could come.

“Neither of you can come and go,” DeVozza said. “They will have meals for you.”

In the end, both Caraveo-Jaime and her boyfriend got tested for coronavirus, but refused to go into isolation to await the results. Caraveo-Jaime did ask for a tent of her own, though, so she wouldn’t have to bed down with others.

As outreach workers continued to mill about, identifying homeless people to test, a man began chasing a woman, attempting to beat her with his cane. The workers tried to keep the man away from her before calling the police.

The incident cut the day of testing short. Still, Fernando was happy the team swabbed as many homeless people as they did and got phone numbers for everyone tested.

Outreach workers are doing their best to tell people on skid row to space out their tents and to sleep alone, but those warnings only go so far when there are too many people living in tight quarters. And because of the lack of hotel beds under Project Roomkey, there’s still a demand for large shelters such as the Union Rescue Mission. An outbreak there led to more than 100 cases among homeless residents and staff in recent weeks.

While more than 1,100 people lived at the Union Rescue Mission before the pandemic, it’s now down to 320 people, said the Rev. Andy Bales, the mission’s CEO. The county is starting to move people back to the shelter from isolation, but Bales said the number of residents will likely grow to about 600 people.

UC Berkeley associate professor Dr. Coco Auerswald said it’s difficult to prevent the spread of the coronavirus in large communal shelters. This is why it’s important for public health officials to have a clear picture of who is and who is not sick — particularly among the homeless population who often have pre-existing conditions that make them far more susceptible to COVID-19.

“People need to know why they’re having those symptoms,” Auerswald said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last month said that regular testing should be considered in shelters. “Testing all persons can facilitate isolation of those who are infected to minimize ongoing transmission in these settings,” the agency said.

What’s desperately needed on skid row right now are rapid tests that can spit results out in minutes, not days, Fernando said.

“Trying to track them down 24 hours later is becoming really difficult,” Fernando said. “The follow-up piece for notification has become so hard.”

The day after testing people in the skid row encampment, Fernando and Maradlaga-Esguerra were back at it before 7 a.m.

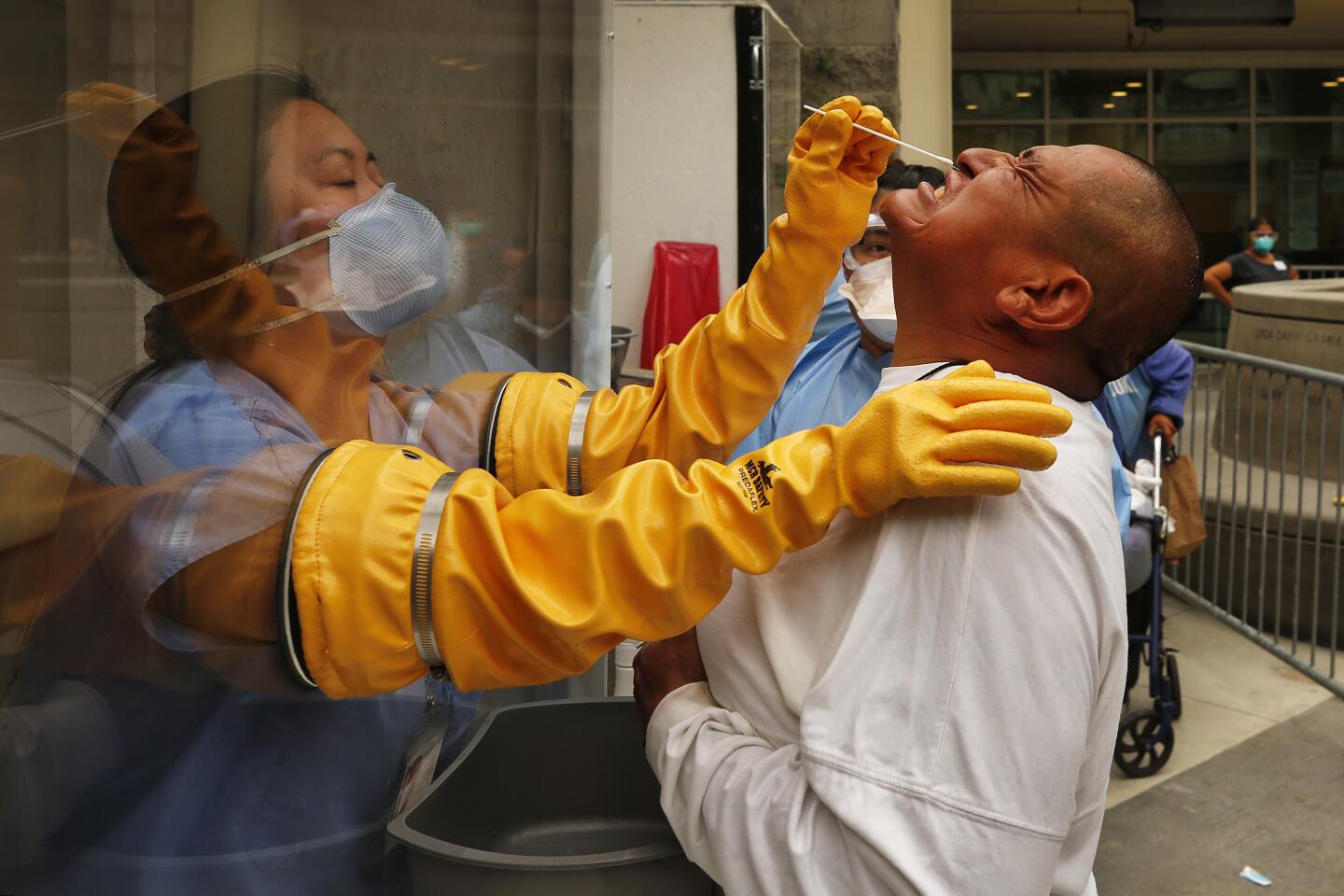

Along with a few other nurses, they had set up what vaguely looked like a kissing booth one might see at a county fair — except each was adorned with Plexiglas and large rubber gloves to administer coronavirus tests without having to constantly change their personal protective equipment.

They wanted to test everyone who had slept in the Midnight Mission’s courtyard. Those who had slept on the cold concrete were now lined up to voluntarily receive a test. After the nasal swab, each received a green bracelet to show that he or she had been tested. Some left their phone numbers. They were told to come back the next day for the results.

For 60-year-old James Olley, it was his first time staying at Midnight Mission. He had recently moved from Fresno looking for work. He said the test was a bit uncomfortable, but no more so than the cold floor he slept on that night.

“If it’s going to make me understand what I need to do, I can bear with it,” he said. “I have no symptoms, but they always say it could come.”

Olley then walked out onto skid row to find a shower and a meal.

Forty-one people were tested that morning. Two were positive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.