A man in tan cargo shorts is lying on the pavement, turning gray with his shirt pulled up to his chest.

An ambulance from Los Angeles Fire Department Station No. 9 shoots down an alley and comes to a stop. Firefighters Brian George and Nicolas Calkins pop out and grab an assortment of medical gear.

“It’s probably heroin, dude,” George says to Calkins, even before kneeling.

They get to work.

“He’s breathing,” Calkins says.

“Narcan?”

“Yeah. I think heroin.”

George checks the man’s pulse while Calkins looks for a vein. The man is not breathing well. They inject naloxone, often referred to by the brand name Narcan, into his neck to counteract the overdose. It doesn’t work.

George, Calkins and their colleagues respond to thousands of calls like this every month while working at one of the busiest fire stations in the nation, in the heart of one of the most troubled places in Los Angeles: skid row. They are the unlikely rank and file on the front lines of California’s escalating homelessness crisis.

The roughly 60 firefighters at Station No. 9 regularly respond to everything from epileptic seizures and overdoses to stalled elevators and full-fledged fires, crisscrossing a district defined by extreme poverty and powerlessness alongside extreme wealth and power in downtown L.A. With residents who are often victims of crime, crippled by addiction and psychiatric disorders from years of living on the street, the firefighters do the best they can with the little they have to offer. Yet the needs are overwhelming.

In 2019 alone, Station No. 9 logged nearly 22,800 emergency calls across just 1.28 square miles — about 7,500 more than the city’s next-busiest station.

Taking care of L.A.’s most vulnerable residents has given these firefighters a unique perspective on the homelessness crisis. Most are empathetic. Some feel isolated or frustrated about the city’s inability to fix what’s happening outside their front door. But rather than dwell on those larger forces or their feelings about it all, they train constantly and joke around with a camaraderie shaped by their shared commitment to one of the city’s most intense jobs.

“We see things that people never see in their lifetimes — we’ll see multiple times in one day,” said Ian Soriano, a firefighter and apparatus operator at Station No. 9.

This is 24 hours in the life of a skid row firefighter.

5:30 a.m.: Fire Station No. 9

Just before sunrise that day, Dan Martinez pulled his Audi A4 onto the sidewalk outside Station No. 9 at 7th and San Julian streets.

The area around the station is abuzz for so much of the day. But at 5:30 a.m., when the C shift arrives, it’s quiet. Martinez, who planned to work 48 hours straight, was the first to show up.

A few minutes later, Jacob Gibson, an attendant on one of the station’s ambulances, came in and started prepping a meal for the 19 firefighters on duty. Tall with curly red hair and a round face, the second-generation firefighter joked about what he thought was the hardest part of his job.

“Cooking for this many people is a pain in the ass,” he said.

Gibson began to cut peppers and whisk eggs as the shift change kicked into high gear. Members of the B shift ambled down from their quarters as members of the C shift lined up their cars in the parking lot next door and waited to cram them behind the station.

5:39 a.m.: Outside the station

An elderly homeless man walks by wearing a faded gray sweatshirt. He stops and turns toward a firefighter.

“My flesh is on fire,” he says. “Put me out.”

“You’re not on fire,” Capt. Branden Silverman responds.

The man keeps walking.

Most of C shift is in the station by 6:30 a.m., but if firefighters don’t arrive even earlier, by 5:45 a.m., others will give them hell. Each member has a job to do. In the morning, they check the gear they’ll be using that day, and situate their pants and boots near the firetruck they’ll be riding in, so they can move quickly when a call comes in.

7:35 a.m.: 632 St. Vincent Court

The man in tan cargo shorts is lying on the pavement, his skin gray.

Calkins, trying to reverse the effects of a heroin overdose, finally finds another vein in the man’s arm and asks for another dose of naloxone.

“If you do it, just go half,” George says.

George rubs the man’s chest and pulls him by his pants onto a gurney. Soon afterward, the man is alert in the ambulance and on his way to an emergency room.

Station No. 9 responds to more medical calls like this than any other fire station in the city, according to the LAFD.

Over nearly two years beginning in 2018, almost 14% of the people that the LAFD took to emergency rooms citywide were homeless. That works out to roughly 81 homeless people a day. For Station No. 9, that ratio was 59%, or about 12 homeless people being brought to the ER every day.

Sometimes firefighters administer naloxone by intraosseous infusion, in which a hole is drilled just below the knee and the drug is injected directly into the patient’s bone marrow. This is the quickest way to bring someone back from an overdose.

There’s a futility in this ritual, though.

On skid row, these firefighters have watched homelessness grow, with the citywide population topping 36,000 as of last year. They’ve seen drug addiction rob many of those same people of their health, making it harder to achieve a stable future away from the street. Yet all George or Calkins or anyone else at Station No. 9 can really do is take them to the emergency room.

Firefighters say they’ve noticed that overdoses often occur when a person with a history of drug addiction gets out of prison or jail and thinks he or she has the same tolerance for heroin as in the past.

“You think your body is used to it,” George said. “You OD a lot quicker.”

In an effort to reduce the workload, the LAFD recently launched its Sober Unit to transport intoxicated people to a center on skid row. Also, a modified wildland firefighting truck known as a “fast-response vehicle,” or FRV, now prowls downtown responding to calls.

The department has heavily publicized these pilot programs. The problem is neither operates on weekends.

“They really push the FRV units,” Capt. Raymond Robles said, “but we’re here every day.”

8:15 a.m.: Back at home base

By 8:15 a.m., the C shift had received 10 calls for help. In the previous 30 minutes, there had been five, nearly all of them on skid row.

Returning to the station, Gibson trudged back to the stove.

“I hope they didn’t burn anything,” he said, knowing that he’d hear it if his fellow firefighters weren’t pleased with their burritos. “All right,” he said a few minutes later, “breakfast is ready. Come and get it.”

The station’s 19-member C shift — all of them men — assembled in the kitchen. Capt. Larry Salas ran through the schedule for the week.

It’s a challenge to keep Station No. 9 fully staffed. Some firefighters blame the stigma of homelessness in their district. The volume of calls and the intensity of the work mean firefighters looking for easy overtime aren’t flocking there.

As a result, on the day The Times visited, one firefighter was working for his fifth straight day.

After roll call, Robles, the station’s longtime leader, took over the meeting. An affable and stocky man, he is part father and part camp counselor to his cohort of younger firefighters, who are intensely loyal to him.

“We’re going to go to the Hotel Baltimore and throw the stick,” he told the team, referring to practice climbing the ladder. “Everyone is going to climb the stick and work our way down.”

Next to speak is Tony Navarro, who, as the most senior member of Station No. 9, is the bull firefighter. He has been at the station for 11 years; before working there, he’d never seen skid row.

On his first day, Navarro responded to a medical call to find a man without feet in a wheelchair. His legs were wrapped in plastic, and maggots were eating away the flesh underneath. When he and other firefighters pulled the man out of his chair, they found that his whole backside was raw and maggots were crawling over his body, top to bottom.

“It smelled like a dead body,” Navarro said. “That was my first day, and it was all downhill from there.”

‘It smelled like a dead body. That was my first day, and it was all downhill from there.’

— Tony Navarro, firefighter

Burnout is the biggest enemy of trying to be an effective firefighter at Station No. 9, he said. The constant calls, constant horror and constant fatigue add up to high turnover. He recalled dozing off at the wheel several times on his commute home. More than once, he said, California Highway Patrol officers pulled him over.

These days, Navarro said, he finds time to kick his feet up and clear his head by sleeping for a few minutes or watching a movie. Finding those quiet moments is important, he said. Otherwise you won’t make it through the day — physically or emotionally.

For many members of the station, responding to calls in ambulances is the hardest part. “You’re inundated with patients,” Navarro said. “It gets to you.”

Of Station No. 9’s roughly 22,800 emergency calls last year, about 18,850 were medical, according to the LAFD.

“Half of us wouldn’t want to be here if it was just that,” Navarro said.

9:46 a.m.: 501 S. Los Angeles St., Baltimore Hotel

Two engines and one ladder pull out of Station No. 9 and enter the heat and traffic of a Saturday morning in downtown Los Angeles. The long truck comes to a stop on 5th Street and blocks a lane of traffic.

The truck’s ladder rises and settles next to the building’s roof. The men line up to climb and discuss how to carry gear up the ladder.

“The most dangerous part is the transition,” Navarro says.

Two years ago, during a training exercise at a building a lot like the Baltimore Hotel, a member of Station No. 9 — Kelly Wong — lost his footing and fell from the ladder onto a firetruck below. He died two days later.

Firefighters are quick to say they do this work for guys like Wong, whose photo is everywhere in the station. They’re less willing to talk about what happened on that day.

Soriano, the apparatus operator, worked the same shift as Wong but was off the day his colleague fell. He had been driving to a wine festival with his girlfriend but turned around and headed to the hospital when he heard what had happened.

“A lot of the guys were really good friends with Kelly. Seeing them broken was terrible. If we don’t get an opportunity to practice this scenario,” he said, referring to climbing the ladder, “we’ll be in trouble when there’s a more stressful scenario when someone is hanging out a window and a fire is blazing. We have to do it, man. We do it in memory of him.”

Soriano has been with the LAFD for 13 years and with Station No. 9 for four years. After responding to dozens of calls for several days in a row, the grim nature of the work sometimes blurs together.

“It wears on your patience, because a lot of the homeless people, we know them by name, and they’re doing the same thing over and over,” he said. “We take a guy to the hospital and he’ll be right back out at 2 p.m. There’s a shock when you first get there and you have to learn how to deal with that over and over again.”

Embracing stoicism, Soriano said, helps him deal with the perpetual stress.

1:38 p.m.: 300 Santa Fe Ave.

Firetrucks and an ambulance scream through skid row on their way to an apartment building. A man has fallen six floors after taking a wrong step while fixing an HVAC system on the roof.

The firefighters find him moaning, face down in a pool of blood. His arms and legs point in unnatural directions.

Gibson runs over and kneels down, attempting to get a pulse and sense of the severity of the man’s injuries. The man’s moans grow louder as the firefighters contemplate how to get him onto a gurney.

“It’s going to be uncomfortable no matter what,” Gibson says, cutting off the man’s shirt.

Another firefighter grabs him by his pants and helps flip him over.

“He broke a lot of things,” Gibson says.

6 p.m.: A quiet moment

As 6 p.m. approached, Gibson prepared dinner. While waiting, firefighters cleaned the station, tinkered with faltering exhaust pipes and examined a new ram bar, a firefighting tool for breaking through locks, doors and walls.

In this quiet moment, Michael Villata, an 11-year LAFD veteran, said he’s often thinking about the disorder that surrounds Station No. 9.

He said he and his colleagues know rising rents have contributed to the growing number of people living on the street. But he also blames the nexus of mental illness and drug abuse, and what he sees as a hesitancy among Los Angeles police officers to deal with homeless people and their encampments.

In some cases, Villata speculated, the breakdown of families has left people without the support they need to be successful in life.

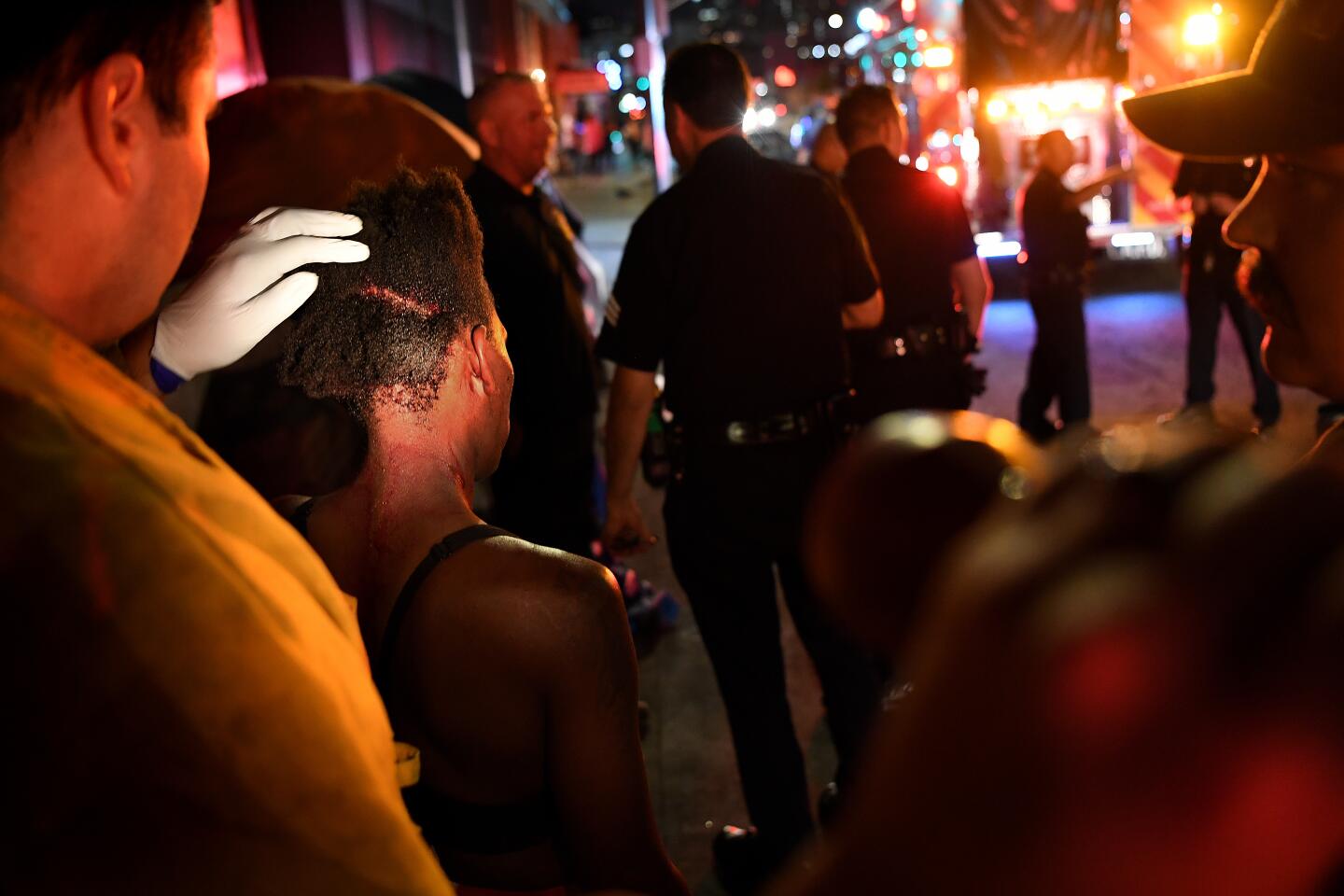

Skid row can be dangerous. Firefighters said they have been threatened while responding to calls. Homeless people have brandished knives, and others have picked up shovels to swing at them.

“We’ve been punched, spit at, choked,” Robles said.

Specific procedures for dealing with such incidents exist, but they still happen often enough that firefighters say they worry about ending up in a violent confrontation when responding to calls. It doesn’t stop them from caring for people on skid row, though.

Villata said he tries to support homeless people — one man in particular, who goes by the name Mango and lives in a tent across the street from Station No. 9.

Mango moved to Los Angeles from Florida and has become the firefighters’ greatest champion — often wearing a T-shirt or a hat with Station No. 9’s logo. Sometimes he helps clean up after a fire is extinguished, and when gear gets stolen from trucks, Mango is usually the one who will venture out to find it.

More often, he stops by just to hang out and talk with the firefighters.

Over the summer, Villata rebuilt Mango’s motorbike, but it was stolen days after he delivered it.

“When I gave him the bike, he cried. He was really happy…. I saw him a few days later and he was devastated that it got stolen,” Villata said. “I just felt horrible for Mango because of how grateful and happy he was. To have something taken from him — just watching it sucks.”

6:48 p.m.: Station No. 9 TV room

Navarro’s feet are up and his eyelids are drooping. A movie is playing on the big screen as a homeless man walks into the station.

“If I could just get some sleeping pills,” he says.

The man’s thumb is nearly ripped off, pointing in an odd direction.

The man explains how he recently had surgery and how he had taken the cast off prematurely because his hand hurt. He also tells firefighters that he missed a follow-up appointment with a doctor.

“We don’t have any,” firefighter Eric Shinn tells him. “Go to the drugstore and get some NyQuil maybe. You can’t be missing appointments.”

Shinn wraps the man’s hand and finds a piece of cardboard to fashion a makeshift splint.

The man leaves.

Such grim scenes drive firefighters to find ways to escape and relax. They pull lots of pranks on one another — like a seemingly serious “training session” ordered by Robles. It turned out to be a younger firefighter swinging nunchaku as his colleagues broke down in laughter.

There’s lots of amusement in these moments — a brief respite from what’s happening outside.

Station No. 9’s members are a tightknit crew. They vacation together. Their families grill together. Soriano recently led a crew of his fellow firefighters on a snowboarding trip to Austria. They also went to Chile and Japan.

“There’s a brotherhood that you can’t really speak about unless you have been there,” Soriano said. “We’re involved in each other’s lives. We hang out with our girlfriends and wives. We go on trips, and we have a lot of fun at the station.”

Another way firefighters let off steam is to play handball. It’s the LAFD’s official sport, and tournaments often attract old-timers who worked at the station decades ago. Sometimes they play in their socks to decide who will do dishes after dinner.

While a game was underway, Soriano and Robles sat in the kitchen and discussed how firefighters were adjusting to life at Station No. 9. Some were struggling with how much time they had to spend responding to medical calls.

It’s common during the first year working on skid row for some firefighters to be sick all the time until their bodies adjust to the stress. Firefighters often spend their first year battling colds and feeling generally unwell.

“It’s something like your freshman 15,” Soriano said, comparing it to the belief that many college students gain weight in their first year.

He blamed it on the lack of sleep and unceasing exposure to the generally unhealthy environment of skid row.

“The hotels, the tents — it’s not necessarily the most clean place to operate,” Soriano said. “I got sick. It’s not like you’re throwing up. You’re just sick constantly.”

11:38 p.m.: 118 E. 6th St., Cole’s French Dip

Engine 209 pulls out of the station, and Mango steps into the street to block traffic. This happens a lot.

Firefighters arrive at Cole’s French Dip and find a man flat on the ground. Patrons are standing around, wondering what’s happening.

Villata digs into the man’s pocket and finds a needle. His pupils are uneven.

They give him a dose of naloxone and his vitals return to normal.

“Let’s go,” Capt. Jim Duffy yells.

“Captain is tired,” Gibson says to no one in particular.

4:47 a.m.: 1301 N. Main St.

Chatter over the radio alerts Station No. 9 to a fire in a neighboring district. Firefighters arrive to find an abandoned building, flames erupting from its mezzanine.

Robles grabs a saw to cut holes in the wall and ceiling. Soriano grabs a fan. They move room to room, putting out remnants of the conflagration.

Navarro pulls off his breathing mask.

There were 82 incidents in 24 hours.

Navarro had just worked 72 hours. Robles was scheduled to do another shift.

When the firefighters return to Station No. 9, the A shift has already arrived and is getting situated. Mango is outside grilling food that he intends to sell. Another day at the busiest fire station in Los Angeles has begun.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.